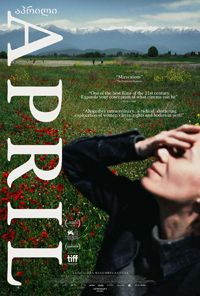

A Vindicated Woman: Kulumbegashvili Constructs Potent, Profound Study in Body Horror

I do not wish them [women] to have power over men; but over themselves,” wrote Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley in The Vindication of the Rights of Women all the way back in 1792, one of the earliest publications of feminist philosophy. Although many details about her personal life obfuscated her literary contributions until recently, including coverage regarding multiple suicide attempts, she died of septicemia days after giving birth to her daughter, Mary Shelley (who would later write Frankenstein). It’s been over two centuries since this publication and still we have yet to see transformational equanimity which would satisfy her wish. The tragedy of Wollstonecraft and one of the enduring templates of horror written by her child come to mind in a much different kind of offering, Georgian filmmaker Dea Kulumbegashvili’s exceptional sophomore film, April. Much like her formidable debut, Beginning (2020), about an attack on a Jehovah’s Witness community which causes significant ripple effects for all involved, her latest might seem like an arduous process to many. Long, distilled sequences with plenty of static shots abound. But the brooding stylization quietly transports us into the dark, dreadful places inhabited by its protagonist. We’re led down an austere path of self destruction for one woman who may be seeking expiation, but really has taken it upon herself to bear the burden of womanhood in an environment where the sacrifice of one is necessary for the survival of all. As one character remarks to her, “No one will thank you and no one will defend you.”

I do not wish them [women] to have power over men; but over themselves,” wrote Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley in The Vindication of the Rights of Women all the way back in 1792, one of the earliest publications of feminist philosophy. Although many details about her personal life obfuscated her literary contributions until recently, including coverage regarding multiple suicide attempts, she died of septicemia days after giving birth to her daughter, Mary Shelley (who would later write Frankenstein). It’s been over two centuries since this publication and still we have yet to see transformational equanimity which would satisfy her wish. The tragedy of Wollstonecraft and one of the enduring templates of horror written by her child come to mind in a much different kind of offering, Georgian filmmaker Dea Kulumbegashvili’s exceptional sophomore film, April. Much like her formidable debut, Beginning (2020), about an attack on a Jehovah’s Witness community which causes significant ripple effects for all involved, her latest might seem like an arduous process to many. Long, distilled sequences with plenty of static shots abound. But the brooding stylization quietly transports us into the dark, dreadful places inhabited by its protagonist. We’re led down an austere path of self destruction for one woman who may be seeking expiation, but really has taken it upon herself to bear the burden of womanhood in an environment where the sacrifice of one is necessary for the survival of all. As one character remarks to her, “No one will thank you and no one will defend you.”

The opening shot of the film is of an obscure figure, something not quite human, and seemingly unformed. The suggestion of breasts confirms it’s a female, deformed by a shell of clay, walking away on a watery surface. We’re next treated to the filming of a live birth, moments later confirming the baby was stillborn. Nina (Ia Sukhitashvili) is the hospital’s head OB-GYN, and she’s called in for questioning by the child’s father, who has filed charges with police. Nina is asked to explain herself by the head doctor (Merab Ninidze), who assigns her colleague (Kakha Kintsurashvili) to conduct an investigation. We learn intermittent bits of information about Nina’s tenure at the hospital, where she is unliked by nearly everyone, the investigation being led by a man she had a romantic relationship with eight years prior, who she requests in private he conduct his investigation fairly. The only thing she has to lose is her job, she tells him. But Nina has other proclivities which seem questionable to her colleagues, including the rumor she performs free abortions for women living out in the villages without the ability to travel to Tbilisi to procure an illegal abortion or afford birth control. Nina also has a penchant for old school cruising most often associated with gay men, driving around to approach random strangers, some who are physically abusive, to engage in no-strings-attached sex.

Her journeys through the villages eventually leads her to a deaf and mute teenage girl who is pregnant, the mother unsure of who the father could be, only knowing a pregnancy out of wedlock would prove to be ruinous for her family. In one painstaking sequence, we focus on the girl’s heaving abdomen as the abortion is performed on a kitchen tabletop. Outside, the unpredictable April weather conjures a metaphorical perfect storm, trapping Nina’s car in the mud. She’s forced to return to the same house, where the girl’s father now eats dinner on the same tabletop. Finally back at the hospital for her next shift, we witness Nina perform a cesarean on another woman, this time a successful birth. In essence, she serves as a revolving passageway for life and death. In the film’s final moments, the investigative results concerning the stillborn infant and the shocking aftermath of an abortion will rear their heads simultaneously.

In many ways, April feels like a Neo-realist body horror film, an excruciatingly intimate portrayal told from what often feels like a real-time perspective of a woman who has the power to correctly administer her skills even under adverse conditions. But she cannot control every aspect of these situations. Essentially, it’s a film about control over one’s body, and like her previous film, often feels reminiscent of Chantal Akerman’s groundbreaking Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). Visual comparisons to some masterworks by Carlos Reygadas, Cristian Mungiu, and Sergei Loznitsa are also readily apparent. But if Akerman’s classic was dealing with the omnipotent presence of time, Kulumbegashvili is innately interested in space. Or, rather, occupied space.

It’s a long while before we get anything near a close-up of the characters, including Kulumbegashvili’s returning lead Ia Sukhitashvili. DP Arseni Khachaturan, who lensed Beginning (as well as Luca Guadagnino’s Bones & All, 2022, one of this film’s producers) forces us to marinate in these spaces, with brief reprieves of movement where Nina is driving to and from, eventually revealing her destinations are sometimes unpredictable. The barking of dogs, like nature’s weathervane for imminent danger, often churn in the background. An aside involving cattle, including a mother cow and her calf situated in the same framed space as the characters, adds to the alignment of constriction with the film’s women. Meditative long shots of distant figures in hallways or rooms begin to form a pattern. A room, much like a womb, is a space designed to be occupied. Slowly, these figures take up more space, impregnating the frame. Bodies also serve as literal landscapes, the extreme outlines of which are sometimes presented as initially indiscernible at a glance. The nude torso and genitals of her ex-lover prominently suggests several ideas, one being the part of his body most useful to her. But this sexual reunion is visualized with Nina as the mud woman, a creature we consistently return to, with a similar breathing pattern to Nina, once we realize it’s from her perspective many sequences take place, as if we were inside her body.

Nina’s early hook-up with a violent hitchhiker reveals an off the cuff story from her childhood, where she and her older sister snuck out on one family vacation to swim in a forbidden lake which was used for breeding fish. Her sister became stuck in the mud, unable to free herself. All Nina could do was cry helplessly, unable to call for help due to their transgression and too afraid to get down into the mud for fear of also becoming stuck. And it’s the place where she’s now seemingly been emotionally stuck for her entire life, making her the mud creature we see shuffling endlessly about. When she returns to her lover, it’s as this creature, because, once again, she’s stuck between a rock and hard place, using her body to reignite his alliance. When he questions Nina about why she doesn’t just let the responsibility she shoulders fall to local nurses, who often perform illegal abortions for extra cash, she insists she is better qualified. “How can I deny them?”

While it may seem like April drifts into stagnation, every visual moment is feeding into the themes of the film, including the multiple escapes into the mercurial nature of spring, rife with blossoming fertility but also presenting a fragile landscape vulnerable to destruction. The final frames reach a thematic blend of perfection, as Nina is questioned beneath a wall clock, ticking endlessly to suggest she’s potentially reached the inevitable fate she cannot escape.

Merab Nindize, a noted Georgian character actor who’s also appeared in many American features (as well as Kornel Mundruczo’s 2017 feature Jupiter’s Moon, a filmmaker who also directed the thematically similar Pieces of a Woman in 2020), is utilized effectively, his bedside manner suggesting that, begrudgingly, he’s perhaps not on the side we expect him to be. “Do you know how laws work?” he glibly asks Nina. “You have to follow the law if you want to work.” But alas, despite his administrative rigidity, he also has skin in the perilous game of healthcare vs. legality. “All the sacred rights of humanity are violated by insisting on blind obedience,” wrote the eternal Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley. Sometimes turning a blind eye is the ultimate saving grace, no matter the motivation. And as we drift off with the shambling mud woman, the end credits finally descend upon an exceptional, cinematic tableaux.

Reviewed on September 5th at the 2024 Venice Film Festival (81st edition) – In Competition section. 134 Minutes.

★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆