Forget the hype: Ferrara’s end-of-the-world reverie puts other apocalypse movies to shame

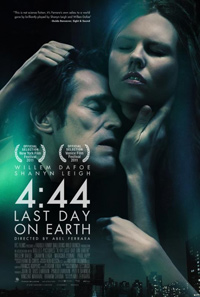

The countdown to the apocalypse becomes a celebratory wake in Abel Ferrara’s transcendent 4:44: Last Day on Earth. Eschewing sci-fi escapism for a raw and intimate portrait of a New York artist couple (Willem Dafoe, and Ferrara’s real-life redhead girlfriend, Shanyn Leigh) riding out the end of times — guaranteed to hit at 4:44AM– in their Lower East Side apartment, Ferrara’s personal film is likely to flummox filmgoers and critics inured to the cheap thrills of CGI bombast and fashionably empty nihilism. Ferrara has no interest in dealing his audience a death fetish fix; his apocalypse movie is, instead, all about life.

The countdown to the apocalypse becomes a celebratory wake in Abel Ferrara’s transcendent 4:44: Last Day on Earth. Eschewing sci-fi escapism for a raw and intimate portrait of a New York artist couple (Willem Dafoe, and Ferrara’s real-life redhead girlfriend, Shanyn Leigh) riding out the end of times — guaranteed to hit at 4:44AM– in their Lower East Side apartment, Ferrara’s personal film is likely to flummox filmgoers and critics inured to the cheap thrills of CGI bombast and fashionably empty nihilism. Ferrara has no interest in dealing his audience a death fetish fix; his apocalypse movie is, instead, all about life.

Anger, love, lust, terror, joy, regret: Ferrara depicts life itself in its fullest spectrum as apocalypse looms, recognizing that life is always lived under the impending certainty of death. As one character in ‘4:44’ says, “The world’s been endin’ ever since it started, man.”

Willem Dafoe is Cisco, an actor living with his younger painter girlfriend Skye. They represent an old-guard downtown NY bohemianism that has slowly been evaporating over the last 20 years, scattered to the winds by rent hikes, a general erosion of the perceived value of alternative culture, and the locust swarm of vapid hipsterism. Cisco’s an ex-junkie feeling the itch for a doomsday score; Skye’s as committed to her craft, despite the sudden negation of posterity, as she is to emotional overreactions in her personal life. In other words: they’re artists, they’re in love, and in less than 24 hours, everything’s going to hell.

Friends, daughters, mothers, and ex-wives are skyped; Chinese food is ordered (and delivered!); there’s a lot of sex, a few recriminations, and the endless white noise of media and TV talking heads trying, and failing, to make sense of it all. In this regard, New Yorkers are in for a special treat: Ferrara includes a gently humorous, and unexpectedly moving, final sign-off from the city’s most beloved news anchor, NY1’s Pat Kiernan. The same end is coming for us all, Pat assures us, regardless of “where you live, or how much money you have.”

As he did with the Mets’ unlikely (and of course, given that it’s the Mets, imaginary) World Series comeback from down 3-0 in ‘Bad Lieutenant,’ Ferrara revealingly parallels his characters’ predicament in ‘4:44’ with a sporting event — here, it’s the Green Bay Packers’ victory, spearheaded by head coach Vince Lombardi, in the 1967 Super Bowl. Cisco was at the game — the doc footage he watches on TV might be his own childhood memory (this entire sequence was likely generated by Dafoe himself, who is originally from Wisconsin). Played in inhumanly cold conditions, the game comes down to the final 16 seconds (game clock, one might ask, or doomsday clock?). Inches from the goal line, Packers’ QB Bart Starr calls a time out to complain to Lombardi about the icy footing. It might be Ferrara, or an even higher authority, speaking through Lombardi’s reply: “Just run the damn play and let’s get the hell out of here.”

Dafoe is his usual magnetic, adventurous self. He and Ferrara come up with some classic moments. Hours from annihilation, Dafoe methodically shaves with a straight razor. Skye asks him why, and he answers with his inimitably devious grin: “I know you like it smooth.” Or watching the Dalai Lama on TV and fiercely urging his holiness to answer “Yes! YES!!” when asked by the interviewer, “Is money the source of all evil?”

Ferrara’s films are most exciting when they follow in the spirit of his artistic godfather John Cassavetes and break completely with the conventions of film language. Not since 1998’s visionary ‘New Rose Hotel’ has he (along with editor Anthony Redman) conjured up the kind of haywire reveries as we find here in the meditative hallucinations of Cisco and Skye. Ferrara’s apocalyptic dream is collaged together from found footage, B-roll miscellany (at one point, Dafoe dreams of his own legendary stage performance in The Wooster Group’s ‘The Hairy Ape’), web-cam live feeds transmitting to no one, spiraling off into the void. This is New York filmmaking with roots, demonstrating a kind of artistic institutional memory of the heady avant-garde tactics of New York filmmakers of the 60s, 70s and 80s.

Younger generations of New York fiction filmmakers should be paying attention: Ferrara, the wise seer, is providing a model for how personal filmmaking can ascend from masturbatory self-fixation to become a form of universal expression; they ought to see ‘4:44’ as a taunting challenge to evolve past the fecal-obsessed infantile stage of development, and achieve instead a larger humanistic perspective.

Ferrara’s version of the end of the world stands alone in contrast to the recent rash of apocalypse movies. An unavoidable comparison must be made to Lars von Trier’s ‘Melancholia.’ Von Trier is a great artist whose impulse towards self-loathing sadism has suffocated his last two movies. What Charlotte Gainsbourg did in repulsive close-up to her own organ of pleasure (perhaps, for better or worse, the most despicable shot in the history of cinema) in the nasty ‘Anti-Christ,’ von Trier does to his own creative impulse halfway through ‘Melancholia.’ It’s as if he can’t tolerate his own natural ability to provide pleasure or consolation to an audience, or himself. Instead, he performs public self-castration on the silver screen, and insecure critics afraid to be ostracized from the consensus of their peers refuse to call him out on it.

It’s not just von Trier that Ferrara stands apart from: Even the otherwise sensitive and engrossing apocalypse-themed ‘Take Shelter’ ultimately nosedives into ugly patriarchal reprimand. “You were wrong, and I was right!” these movies bluster like a playground bully, “Admit it!” Ferrara, superior as an artist and as a compassionate human being, has no interest in using his art to play “uncle” with his audience.

For Ferrara, the apocalypse starts where life never left off: two lovers clutching one another out of fear and desire, framed by the background of a fresh canvas — the night sky transmogrified, the universe re-created in oils — a whispered “I love you,” a hushed “forgive me,” a blinding whiteness, and the cosmos-cracking authority of an electric guitar.

Reviewed on October 16th at the 2011 New York Film Festival.