Wedging The Closet Door Open In Uganda

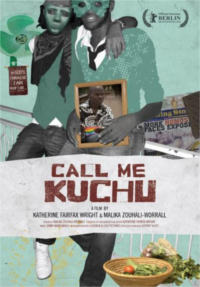

In the United States, the last few decades have been tarnished with the debate over whether or not homosexual couples should have the same legal rights as traditionally married straight couples, but as atrocious as that contention is, it pales in comparison to the injustices that gay citizens of Uganda must endure. There, approximately 95% of the population believes that homosexuality is a blasphemous choice made by perverts hellbent on summoning the wrath of God to destroy Uganda just as he had Sodom and Gomorrah, and for this, they deserve death. This extremist view has ironically been cultivated by wealthy American Evangelical Christian groups and successfully spread to the point where there is now a proposed piece of legislation called the Anti-Homosexuality Bill that, if passed, would make homosexuality punishable by death. Yet, a few brave souls still fight the good fight against obtuse hatred for the betterment of human rights. With sentiment and conviction, several of these men and women open up to first time docu directors Katherine Fairfax Wright and Malika Zouhali-Worrall in their provocative and heartbreaking debut, Call Me Kuchu.

In the United States, the last few decades have been tarnished with the debate over whether or not homosexual couples should have the same legal rights as traditionally married straight couples, but as atrocious as that contention is, it pales in comparison to the injustices that gay citizens of Uganda must endure. There, approximately 95% of the population believes that homosexuality is a blasphemous choice made by perverts hellbent on summoning the wrath of God to destroy Uganda just as he had Sodom and Gomorrah, and for this, they deserve death. This extremist view has ironically been cultivated by wealthy American Evangelical Christian groups and successfully spread to the point where there is now a proposed piece of legislation called the Anti-Homosexuality Bill that, if passed, would make homosexuality punishable by death. Yet, a few brave souls still fight the good fight against obtuse hatred for the betterment of human rights. With sentiment and conviction, several of these men and women open up to first time docu directors Katherine Fairfax Wright and Malika Zouhali-Worrall in their provocative and heartbreaking debut, Call Me Kuchu.

The word ‘Kuchu’ is a loving epithet for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender men and women, and the term sits quite well with the film’s predominant focus, LGBT activist David Kato, Uganda’s first openly gay man. Soft spoken and light hearted, Kato’s toothy grin and bony frame hides a protective rage against oppression while local newspapers herald headlines like, ‘HOMO TERROR! We Name and Shame Top Gays in the City,’ placing many of those he aims to safeguard in mortal danger. Placing himself in the crossfire of courtrooms and television interviews, the coolly composed advocate convenes with legal council, reaching out to the UN and other outside forces to bring attention to the bigotry running wild throughout his beloved home country. At home behind a tall concrete wall that surrounds the property, he hosts drag themed parties to celebration of their true selves amongst friends who know the truth.

Horrifically, bigotry gets the best of Kato, as he was found brutally murdered in his own home after a year of filming with Wright and Zouhali-Worrall. His funeral served as a battle ground for grieving gays and self-righteous radicals, a savage awakening for a community suppressed. One supporter, the exiled Bishop Christopher Senyonjo, publicly pledged his support for the LGBT community despite the dangers. Meanwhile, some decided this was the final straw, packed their belongings and fled the country.

Following all of these events with profound intimacy, the filmmakers are privy to the most private part of these peoples lives, allowing each one to tell their own tales of terror and self acceptance. But it’s not just a partisan portrayal. The politician spearheading the Anti-Homosexuality Bill is give the chance to voice his opinion. The editor of the defamatory local newspaper, Rolling Stone, is seen before the camera smirking and giggling about his part in the smear campaign to snuff out homosexuality in Uganda. And one of the many religious crusaders that fund the legal battle against LGBTs is given his 15 seconds of fame as well. Juxtaposed with the mild mannered intelligence and honesty of Kato and his cohorts, this makes for a supremely shocking twilight zone of religious extremism obsessed with the private lives of others.

The film’s intimate examination of a nation behind the times and a man whose achievements were recognized too late makes for a unique portrait, but it’s not singular in terms of subject matter. Roger Ross Williams’s God Loves Uganda broaches the topic via the world view of American Evangelists a la Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady’s Jesus Camp, touching on Kato and Senyonjo‘s bearing while thoroughly exploring the extent of fanaticism outpouring from the church, but it never breachs the same level of affinity for their subjects or urgency of the socio-political state of Uganda itself. It is this critical propulsion, spawned by an amorous rendering of Kato, his friends and their astute resolve, that allows Katherine Fairfax Wright and Malika Zouhali-Worrall’s Call Me Kuchu to rise above its generally bland production to crucial political importance.