Make Me Lose My Breath: Linklater Meddles in Manicured Homage

It’s unclear what the exact purpose of Nouvelle Vague is meant to serve, other than paying irreverent homage to Jean-Luc Godard and the making of his iconic debut feature, “ Breathless,” (1960). But a deference to both the filmmaker and this lionized period of filmmaking doesn’t always feel enough to justify Richard Linklater’s studious reimagining of a twenty-day guerrilla film production which would become a cornerstone regarding the production of cinema and how we talk about it. The second feature film from Linklater in 2025, following the Berlin Film Festival premiere of Blue Moon, which pays tribute to Broadway lyricist Lorenz Hart in the waning of his career, approaches the personality of a major artist from the opposite end of his trajectory. But there’s little to dig into considering it’s a superficial jest about a notable group of people who were involved in the making of a film that almost never was.

It’s unclear what the exact purpose of Nouvelle Vague is meant to serve, other than paying irreverent homage to Jean-Luc Godard and the making of his iconic debut feature, “ Breathless,” (1960). But a deference to both the filmmaker and this lionized period of filmmaking doesn’t always feel enough to justify Richard Linklater’s studious reimagining of a twenty-day guerrilla film production which would become a cornerstone regarding the production of cinema and how we talk about it. The second feature film from Linklater in 2025, following the Berlin Film Festival premiere of Blue Moon, which pays tribute to Broadway lyricist Lorenz Hart in the waning of his career, approaches the personality of a major artist from the opposite end of his trajectory. But there’s little to dig into considering it’s a superficial jest about a notable group of people who were involved in the making of a film that almost never was.

What Nouvelle Vague feels most skilled at is name-dropping, a head-spinning amount of major and minor players who were integral in the French New Wave at least suggesting bibliographical utility. For those wholly ignorant to Breathless or Godard (but who amongst the uninitiated are going to seek out a film titled Nouvelle Vague?), Linklater only concretely establishes a trio of critics from the esteemed Cahiers du Cinema film magazine, influenced by the earlier Italian masterpieces of Roberto Rossellini, godfather of the first ‘crest’ of the rippling wave. Collectively, they would change the face of French cinema, which had heretofore been diminished by post-WWII Americanization (as such, Sylvain Chomet’s Marcel and Monsieur Pagnol, premiering at the same time, coincidentally serves as a fortuitous precursor). In divorcing themselves from their French forefathers, the New Wave crew utilized American iconography as the prism with which to reflect their own rebellious sentiments (the case in point for Breathless being all the Humphrey Bogart idolatry).

The outright disdain the Cahiers crew had for the old guard of the previous generation, sans a select few luminaries, like Cocteau or Melville (but screw Allégret, Duvivier, even Clouzot) isn’t really Linklater’s aim. Instead, he documents the pretentious rise of Godard (Guillaume Marbeck), whose motivation to direct his first feature is partially due to a heated competition with cohorts Claude Chabrol (Antoine Besson) and Francois Truffaut (Adrien Rouyard), both predating him in the New Wave, the latter having just premiered “The 400 Blows,” at the Cannes Film Festival. With a script co-written by Truffaut, producer Georges de Beauregard (Bruno Dreyfürst), fresh off releasing the romantic adventure film Pêcheur d’Islande (1959), feels ready to make a gamble on Godard, especially considering the success with which Truffaut has been met. But Beau-Beau wants a stylish, cheap noir. The shared sentiment between producer and director is that every film needs a girl and a gun, which indeed ends up being the only element remaining intact by the wrap.

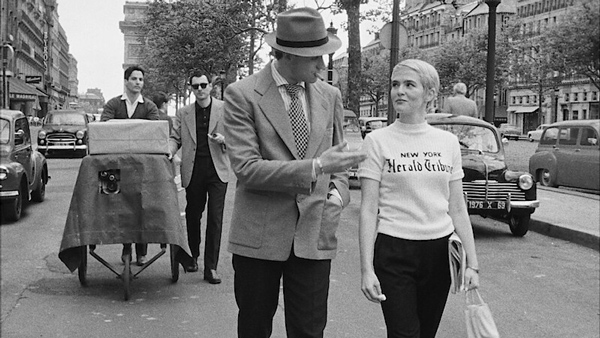

Godard secures his male lead with Jean-Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin), who appeared in his earlier short film. Belmondo in turn is used to clinch Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch), fresh off her second feature with Otto Preminger, Bonjour Tristesse (1958). Her current husband Francois Moreuil (Paolo Luka-Noé) is also interested in facilitating her involvement for his own future prospects as a director. As is to be expected, Godard’s unconventional approach raises alarm bells with his producer and Seberg, who remains unconvinced of her agreement to make the film. However, since her contract with Columbia Pictures had to be bought out for fifteen thousand dollars, it’s in her best interest to complete the shoot.

At most, Nouvelle Vague is mildly amusing, taking an almost Bowfinger (1999) like approach to guerrilla filmmaking. As Godard, Marbeck makes a fine impression of the idiosyncratic persona (and it’s safe to say it’s a better rendering than Michel Hazanvicius’ 2017 feature Le Redoutable, aka Godard, Mon Amour, which showcases the filmmaker during the making of La Chinoise seven years after his debut).

Zoey Deutch is cute and often funny, but hers is a superficial impression of Seberg, including her ability to showcase how well Seberg could speak French vs. her accent used in Breathless. It’s perhaps unfair to compare her to Kristen Stewart’s more somber portrayal in Seberg (2019) during her waning years as a celebrity, but this earlier portrayal certainly does more justice to Seberg’s less than chipper undertones. Essentially, Linklater is applying his own hangout tableaux to the New Wave alumni. But it fails to capture the energy of what exactly made them such trailblazers.

Reviewed on May 18th at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival (78th edition) – Competition. 115 Mins.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆