Thieves Like Us: Reichardt Wanders with an Inscrutable Slacker

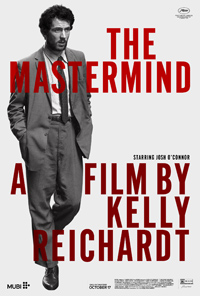

Abstract paintings are not the only undefined objects in The Mastermind, the latest from Kelly Reichardt, who has become a master herself at creating quiet, emotionally resonant characterizations of lonely, isolated individuals struggling to overcome something. Usually, life is happening to them, but the main protagonist of this muted 1970 set tale jumps from the frying pan into the fire thanks to a foolhardy decision which throws his life into chaos. Civil unrest buzzes in the background as anti-war protests engulf the country, and it would seem a collectively frayed moral compass has also eroded the desperate family man looking for a way out of his own stagnation.

Abstract paintings are not the only undefined objects in The Mastermind, the latest from Kelly Reichardt, who has become a master herself at creating quiet, emotionally resonant characterizations of lonely, isolated individuals struggling to overcome something. Usually, life is happening to them, but the main protagonist of this muted 1970 set tale jumps from the frying pan into the fire thanks to a foolhardy decision which throws his life into chaos. Civil unrest buzzes in the background as anti-war protests engulf the country, and it would seem a collectively frayed moral compass has also eroded the desperate family man looking for a way out of his own stagnation.

James Blaine Mooney (Josh O’Connor) is an art school drop out vaguely dabbling in construction, at least as he explains it to his parents (Hope Davis, Bill Camp), a respected Judge and his wife, to whom he already owes a significant amount of money. Married to Terri (Alana Haim), who supports them financially, along with two young sons, little does anyone know James has been planning to steal four paintings by Arthur Dove from the local museum. He’s assembled a team of two men who will put silk stockings over their heads and carry the paintings right out the front door while he serves as the getaway driver. However, when the day arrives, their best laid plans go awry. It’s not long before agents come knocking at James’ door, and so he goes on the run, visiting old friends (John Magaro, Gaby Hoffman) in the countryside. They have no desire to harbor a fugitive, and soon James resorts to petty crime to make a break for the Canadian border.

In many ways, The Mastermind intrigues as a deconstructed heist flick, disarticulated as it is from the expectations of the genre. For instance, compared to Peter Yates’ escapade about the pilfering of a diamond from a museum in The Hot Rock (1972), Reichardt utilizes only the skeleton of a crime caper while instead embracing the suburban malaise of the period. But neither is this a character study of James Mooney, who seems an intelligent, privileged social loafer who has fallen between the cracks of his own life.

It’s unclear what the exact end goal seems to be, as even the planning of the heist fails to break from his matter-of-fact behavior. Where’s his joy? He seems to have none. A conversation with Gaby Hoffman towards the end of the film provides a potential clue regarding why Arthur Dove’s paintings have courted his interest, and it would appear this might have been a desperate ruse to somehow tap into a happier, earlier time in his life.

It’s a scenario ripe for broad comedic strokes, but there’s a solemnity to the interactions between James and his two children. His wife, a muted Alana Haim, arguably seems to be focused on holding everything together whilst her drifting husband borrows money from his fussy mother (a brief but entertaining Hope Davis). Strangely, all the pieces seem to be assembled, but nothing coalesces in ways which draw us into the narrative. A final, karmic explosion ends on a wry note (through the kind of moment you’d expect to see in an episode of The Twilight Zone) but the build up is a glacial display of distraction.

Arguably, this is Reichardt’s way to visualize James’ ennui, a man focused on all the wrong details of his life. We spend long moments with him as he fusses about where to hide the paintings, the shirt’s he’s assembling while on the run, and then a deliberate break from the film’s cinematographic rhythm when DP Christopher Blauvelt observes him doctoring his passport. Of course, it’s all an ironic lark as James Mooney is not a master of anything and his mind’s distracted by obtaining some kind of obscure outcome not necessarily even monetarily beneficial, suggesting this was all an elaborate, subconscious ruse to sabotage his comfortable but boring life. Compared to Reichardt’s greatest hits thus far, it’s her least compelling presentation of a solitary, melancholic character to date.

Reviewed on May 24th at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival (78th edition) – Competition. 110 Mins.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆