Sit & Deliver: Lighton Assumes Positions in Titillating Debut

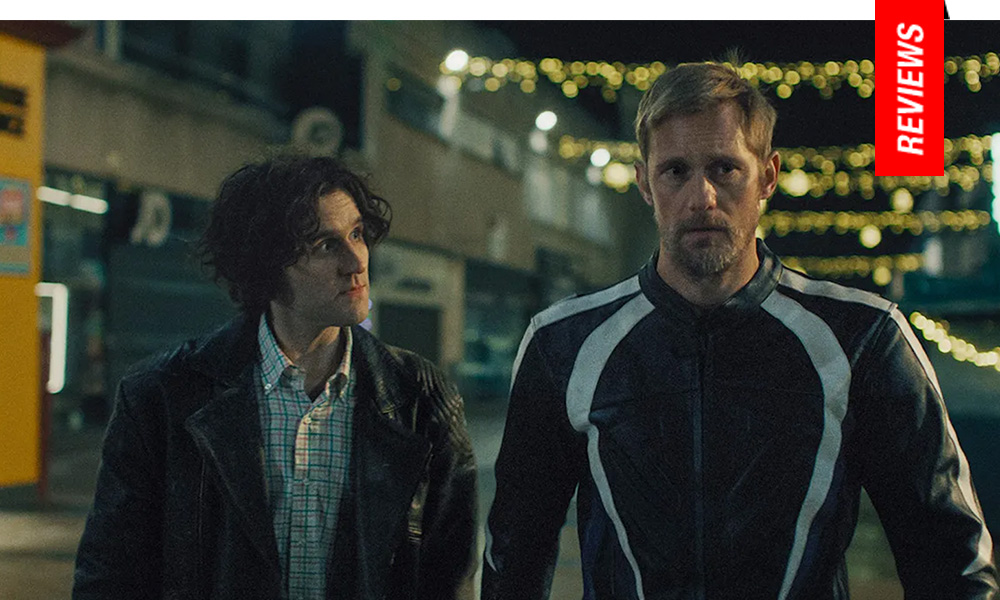

Colin (Harry Melling) is a lonesome young man who lives with his parents (Douglas Hodge, Lesley Sharp) in London. He’s a talented singer, and when an awkward blind date dissipates following a vocal performance at a local bar, he runs into Ray (Alexander Skarsgård), a handsome biker who’s drinking with his crew. A terse exchange leads to what Colin believes is a date, but he follows the tightlipped Ray down a dark alley on Christmas Eve and finds his life transformed. Invited to spend the night at Ray’s home, Colin quickly learns this is not intended to be a romantic relationship, and with little instruction, falls into line as Ray’s submissive sexual partner, to be used solely for Ray’s pleasure (which includes cooking and housework). As time goes on, Colin begins to challenge the restrictive demands of his role, and eventually his own personality tries to surface for air.

The term ‘pillion’ refers to the passenger seat on a bicycle, with additional historical context connoting effeminacy in reference to a light saddle designed for use by a woman. In essence, Colin is this metaphorical appendage for Ray, a side piece, a hanger-on, an unnecessary accoutrement. Since the narrative unfolds from the perspective of Melling’s Colin, we’re led to believe he stumbled upon his intended destiny as a submissive bottom, a vessel for eternal consumption. What heightens the bittersweet tonality of Lighton’s interpretation are Colin’s sympathetic, supportive parents, including Lesley Sharp as his dying mother.

What Pillion highlights is the vast chasm of comprehension between heteronormative relationship sanctions and the reality of more ambiguous, less defined sexual and romantic relationships in a queer community which historically eschewed and then politicized their sexual proclivities in response to the violence, hostility and trenchant erasure demanded by the heteropatriarchy. With formidable sadness, we witness Colin’s parents struggle to comprehend their son’s subservience to the alluring but emotionally vacant Ray, trying to surmise if their child has found happiness. In short, he has, and with a quietly administered bravado, learns to advocate for himself, eventually to the detriment of a relationship which he has used as a defining aspect of his existence.

There’s much to admire in Lighton’s horned up exploration of this liaison, something usually dismissed as the product of kinky hedonism and ultimately not sustainable physically or emotionally for its champions. Alexander Skarsgård is well-cast as a nordic Adonis, whom no outsider can rightly believe is affiliated with Colin. Ultimately, he’s the more pitiable figure, unyielding like a sturdy oak who’s felled by the first strike of inevitable lighting, while the more malleable Colin is the wild reed who will ultimately weather any storm. And yet, the inherent, trenchant beauty standards of their dynamic, which was also readily apparent in Mars-Jones’ text, somehow misses out on something essential regarding the solidification of these roles, the dominant and the submissive. Our culture often dictates desirability, and we’re conditioned to believe a relationship between the likes of Melling and Skarsgård could only be rationalized through the extreme demands of role playing. In other words, there’s an ideology ingrained even within the queer community and its various subcultures believing the only way a man like Colin could associate with a man like Ray is through brutal acquiescence. What seems more compelling are people who subvert these tendencies, for a wide variety of reasons, eschewing societal expectations based on their physical attributes and pursuing their desires whilst essentially swimming upriver, even within the most seemingly accepting environments.

Although Pillion ends on a hopeful note for Colin’s progress towards sexual self-actualization, the film’s resonance isn’t really about him at all. Rather, it’s a blazing reminder of the inherent power in going one’s own way, even when that way isn’t understandable or decipherable to anyone else.

Reviewed on May 22nd at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival (78th edition) – Un Certain Regard. 107 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆