One need only look at the marketing strategy for 1934’s Imitation of Life to see how woefully inept Hollywood was (and in many ways, still is) unable to soberingly deal with the racist realities of American culture. The various taglines would have one believe the film is a tawdry tale about a single mother and her daughter falling in love with the same man, completely ignoring the searing backbone of the narrative regarding the toxic yoke of colorism dividing a Black mother and her daughter irrevocably.

One need only look at the marketing strategy for 1934’s Imitation of Life to see how woefully inept Hollywood was (and in many ways, still is) unable to soberingly deal with the racist realities of American culture. The various taglines would have one believe the film is a tawdry tale about a single mother and her daughter falling in love with the same man, completely ignoring the searing backbone of the narrative regarding the toxic yoke of colorism dividing a Black mother and her daughter irrevocably.

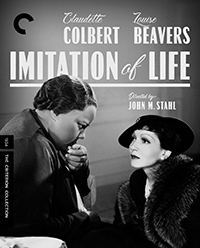

Clearly undermining the intention of Fannie Hurst’s novel, from which it was adapted, there’s still no denying the dramatic imbalance between the juxtaposed pair of white and Black characters, a reality also readily apparent in Douglas Sirk’s more famous 1959 remake (and his swan song), which starred Lana Turner and netted Jaunita Moore an Academy Award nomination. But the original has its own quiet, steadfast flavor, adapted by cinema stalwart John M. Stahl, a director who straddled the silent vs. talkies chasm and wound up being quite an adept master of melodrama (his 1935 title Magnificent Obsession would also be remade by Sirk two decades later). Although best known for his vicious technicolor film noir Leave Her To Heaven (1945) at the tail end of his career, his first crack at Hurst would give us an indelible Louise Beavers performance, even if the marketing would see her eclipsed by Claudette Colbert.

Bea (Colbert), a widowed mother tending to her young daughter Jessie, finds her stressful morning interrupted by the appearance of Delilah (Beavers), who mistakenly shows up to the wrong address to apply as a housemaid. The mistake is a blessing in disguise for both women, seeing as Bea clearly needs assistance and Delilah is seeking a kindly employer who will allow her to live on the premises with her own daughter, Peola, who is so light skinned she passes as white. The two women become thick as thieves, and one morning while enjoying Delilah’s delicious pancakes, Bea has an idea for a business plan, finagling rent for a store front as a restaurant. With Delilah’s secret recipe, the pancakes sell like crackerjacks, and eventually Bea, through the suggestion of an admiring customer (Ned Sparks), expands her sales exponentially through boxing Delilah’s pancake flour (a la Bisquick). But as the women become wealthy from their profits, their private lives are courted by ruinous social misfortune, for Peola insistently denies her Black heritage, going so far as to publicly demean her mother. Meanwhile, just when Bea thinks she’s found love, Jessie also sets her sights on the same man.

Although it’s clearly a product of its time based on its somewhat obvious but apparently subconscious racism, Imitation of Life was far ahead of its time in many ways. Although she wasn’t the advertised star, Louise Beavers is front and center, her storyline packing the greater wallop, and this five years before Hattie McDaniels’ iconic Oscar win for Best Supporting Actress in Gone With the Wind (1939). However, it’s a grim victory, saddled as Beavers is with having to directly employ the cliched stereotypes of the mammy.

In retrospect, the most difficult aspects of the film regard how Bea neglects to assist Delilah with a further education rather than let her accept her social position as a maid. The literal appropriation of Delilah’s skills make Bea a greater entrepreneur than even Mildred Pierce, and yet Delilah downright refuses to sign a contract which would give her 20% (keep in mind there would not be a company, a brand, and eventual franchise, without her) of the business. If that’s not enough to be perturbed by, then there’s the whole heartbreak about the exceptionally neglected Peola, whose identity crisis is hardly attenuated.

The devastating moment where she boldly lies to her mother’s face in public after running away from an all Black college to reinvent herself as a white woman without a past is only negated thanks to the intervention of, well, another white woman. One wishes Bea were more like the flinty spitfire Lily Powers, played ferociously by Barbara Stanwyck in 1933’s Baby Face, a subversive Pre-code delight which found her taking better care of her Black helpmate Chico (Theresa Harris) a hell of a lot more thoughtfully than the shadowy hierarchical friendship allows for in Imitation of Life.

That Peola is played by Fredi Washington, who was actually Black, is another facet which makes Imitation of Life unique, suggesting Hollywood could have actively fostered representation rather than backpedaling specifically when it came to narratives dealing with light-skinned Black characters (fifteen years later, for instance, another ‘major’ melodrama would be Elia Kazan’s 1949 Pinky, casting the white Jeannie Crain as a Black woman).

With the film’s grueling racial dilemma left simmering in the background, the script (co-written by William Hurlbut, with Preston Sturges as one of the several uncredited contributors) reverts drastically into Bea’s late-staged dilemma with a rather enfeebled courtship. Warren William’s Stephen unfortunately becomes the object of her daughter Jessie’s affection, which she uses as an excuse to sacrifice her own happiness. On the sidelines is Ned Sparks as her surprise business partner and pseudo-comedic relief (in ways which Eve Arden would later fulfill for Crawford’s Mildred Pierce, as well). This eventual dominant storyline seems to be both a distraction and an excuse to avoid reconciling Delilah’s reality as well as conveniently override Bea’s guilt as an appropriator, though no one could rightly articulate the troubling catch-22 of Hollywood’s white saviors until they stopped being the preferred focal point.

Final Thoughts:

A classic melodrama, John M. Stahl’s version of Imitation of Life is perhaps a more accurate depiction of partially mislaid good intentions regarding contentious race relations compared to Sirk’s more lavish 1959 version (which made greater attempts at showcasing an underlying Black cultural infrastructure thanks to its inclusion of Mahalia Jackson). But it’s a worthwhile remnant of one of the few impactful leading roles for Black women, played with folksy abandon by an excellent Louise Beavers.

Disc Review:

Criterion presents Imitation of Life with a new 4K digital restoration in 1.33:1, crisply administering DP Merritt B. Gerstad’s frames, which includes a bounty of close-up on both leads (like Stahl, Gerstad also crossed the same cinematic divide, and lensed Tod Browning’s excellent 1927 silent film The Unknown, starring Lon Chaney and Joan Crawford).

Imogen Sara Smith, who authored The Call of the Heart: John M. Stahl and Hollywood Melodrama, contributes an introduction in the special features. A new interview with Miriam J. Petty (author of Stealing the Show: African American Performers and Audiences in 1930s Hollywood) discusses the importance of Louise Beavers and Fredi Washington, while a trailer cut specifically for Black theaters at the time of release is also included.

Film Rating: ★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Rating: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆