To Go On Two Legs: Gregory’s Fascinating Recapitulation of a Cinematic Train Wreck

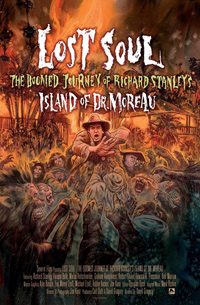

Documentarian David Gregory graduates from an extensive history of shorts with his first feature length achievement, the verbosely titled Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s The Island of Dr. Moreau. However, the title is something of a misnomer, much like another recent examination of a project that never came to fruition with its originating director, Jodorowsky’s Dune. Stanley, who had gained a successful cult following in the early 90s for Hardware (1990) and the Miramax distributed Dust Devil (1992), would engage in the sort of uphill production battle that rivalled historical studio horror stories. Weather, nervous producers, pampered diva personalities, and ultimately, Stanley’s own limitations in reigning in such aggressive setbacks would result in his being fired from the set. However, the strangeness doesn’t stop there. Gregory manages to convey the extremity of a much maligned production, though the absence of several cast members still living inevitably leaves discussion of the final product partially relevant. Instead, the documentary mostly gives Stanley a chance to sound off.

Documentarian David Gregory graduates from an extensive history of shorts with his first feature length achievement, the verbosely titled Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s The Island of Dr. Moreau. However, the title is something of a misnomer, much like another recent examination of a project that never came to fruition with its originating director, Jodorowsky’s Dune. Stanley, who had gained a successful cult following in the early 90s for Hardware (1990) and the Miramax distributed Dust Devil (1992), would engage in the sort of uphill production battle that rivalled historical studio horror stories. Weather, nervous producers, pampered diva personalities, and ultimately, Stanley’s own limitations in reigning in such aggressive setbacks would result in his being fired from the set. However, the strangeness doesn’t stop there. Gregory manages to convey the extremity of a much maligned production, though the absence of several cast members still living inevitably leaves discussion of the final product partially relevant. Instead, the documentary mostly gives Stanley a chance to sound off.

South African born Stanley seemed an inspired choice for an adaptation of H.G. Wells’ famous novel The Island of Dr. Moreau, which had been made twice before, in 1932 as Island of Lost Souls with Charles Laughton, and again in 1977 with Burt Lancaster. New Line Cinema, itself in a sort of experimental stage of branding its output, green lit Stanley’s pitch, who was not yet thirty years old at the time. Conceived as a mid-budget production and meant to be an updated but more faithful adaptation of the novel, Stanley poured himself into the production design and settled on the location of Cairnes, Australia for shooting. But casting woes immediately became a concern, with Marlon Brando coming on board as the doctor, which completely changed the design Stanley had in mind for the character (he originally wanted Jurgen Prochnow).

Surprisingly, according to Stanley, Brando liked him and agreed to do the picture (though it’s here where Stanley’s offbeat spiritual beliefs, mainly that a warlock friend of his basically fixed the meeting ahead of time, adds to the kookiness). But the notoriously difficult Brando became a blessing and a curse. A name that everyone wanted to work with yet not exactly a box office draw, his inclusion meant a higher budget. At the time, Stanley courted Bruce Willis for the role of Douglas and James Woods as Montgomery. But before production began, Willis became embroiled in his high profile divorce with Demi Moore, which held him in the US.

Willis was then replaced with Val Kilmer, and the budget ballooned uncontrollably as Kilmer was then a hot commodity thanks to his superhero role in Batman Forever. Kilmer wanted to work with Brando, but didn’t respect or care for Stanley. The star demanded 40% less shooting days, impossible considering his role as Douglas. So then, it was decided that Kilmer would play Moreau’s assistant, Montgomery, which allotted for less shooting days. This meant knocking James Woods out of the cast, and Rob Morrow of the television series “Northern Exposure” came on board. Meanwhile, Brando’s daughter Cheyenne committed suicide, forcing Stanley to shoot around Brando. And then there was a hurricane.

Producers fired Stanley via his agent and replaced him with veteran auteur John Frankenheimer, who apparently cared very little for the material, but used New Line’s desperation to secure a large sum and a three picture deal. Frankenheimer’s old school sensibilities (he was known for being able to wrangle difficult personalities) drastically changed the attitude on-set, but as several cast members state, including the entertaining Fiona Mahl, who starred as Sow Lady #2, Frankenheimer didn’t make the production any more efficient with a shoot that was supposed to take several weeks ballooning into six months.

Fairuza Balk, who was friends with Stanley, immediately tried to abandon the project, but she, along with others, were held to contract as it would have been too expensive to recast all the players. If anything, it’s Balk’s testimony that makes this all quiet fascinating, relating memories of a tyrannical Frankenheimer and a disinterested Brando, who seemed more intent on purposefully messing with production.

Kilmer and Brando didn’t get along, and the two stars apparently loathed Frankenheimer and vice versa. Marco Hofschneider, who played M’Ling, reveals disgusting anecdotes about both stars, asserts that upon Brando’s insistence, his role was cut down severely as the star preferred to have Nelson de la Rosa appear with him in all his sequences. Rob Morrow, of course, would eventually leave production, to be replaced by David Thewlis, who isn’t mentioned here. It would’ve been great to hear from the actor, who has made his distaste for the production known (and there were reports of a broken leg on set). But he’s nowhere to be found. Not surprisingly, neither is Kilmer.

Interestingly, Frankenheimer had previously assumed responsibilities for two other productions after a director had been fired. One such film was 1964’s The Train, wherein star Burt Lancaster (who also portrayed Moreau) had Arthur Penn fired (and Brando would infamously insubordinate that director on the set of The Missouri Breaks). Another tangent in Gregory’s doc reveals that author Wells was once close friends with Joseph Conrad, but they had a falling out when Wells accused Conrad of plagiarism upon the publication of The Heart of Darkness. Brando, of course, portrayed the enigmatic Kurtz in Coppola’s adaptation of the Conrad novella, Apocalypse Now (1979), and to further enhance the symbiotic relationship, Stanley professed to borrow the notion of the cat woman from Conrad’s novel Outcast of the Islands.

A heady mix of true Hollywood melodrama and intermingling details of bizarre interest dating back to its publication, the saga of The Island of Dr. Moreau makes for potent subject matter. While Gregory’s treatment isn’t as generously charming as the recent and comparable examination of Jodorowsky’s Dune, this is still fascinating, intoxicating stuff. As offbeat and strange as some of Stanley’s statements may be, it’s unfortunate that he faded from sight after the debacle. With a little luck, the renewed interest in his failed project could regenerate some new material, while in true Hollywood fashion it seems that the writers of Hemlock Grove were recently tapped by Warner Bros. to bring yet another adaptation of Wells’ novel to light.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆