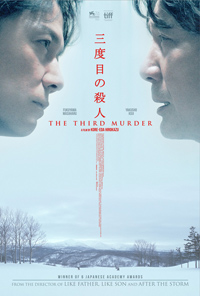

Murder Was the Case That They Gave Him: Kore-eda Mounts Philosophical Crime Thriller

Revered for his finely hewn dramas so often navigating the subtle isolation and desperation visited upon troubled families faced with social, romantic, or economic entanglements, Japanese auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda switches gears with his latest, The Third Murder, a genre influenced crime drama. However, Kore-eda brings his usual aesthetic to a familiar formula, honing in on philosophical articulations of the human condition in the aftermath of a murder as a defense attorney explores the fluctuating perspectives of culpability regarding his admittedly guilty client.

Revered for his finely hewn dramas so often navigating the subtle isolation and desperation visited upon troubled families faced with social, romantic, or economic entanglements, Japanese auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda switches gears with his latest, The Third Murder, a genre influenced crime drama. However, Kore-eda brings his usual aesthetic to a familiar formula, honing in on philosophical articulations of the human condition in the aftermath of a murder as a defense attorney explores the fluctuating perspectives of culpability regarding his admittedly guilty client.

Utilizing some of Japan’s finest and most notable actors to mirror warring sides of discourse, the departure in tone still bears Kore-eda’s refined, controlled aesthetic. Those hoping for a pulpy, genre entry from the director will perhaps be disappointed in a film which otherwise stands as another obvious calling card for Kore-eda, albeit one with a darker tone than usual.

When troubled loner Misumi (the famed Koji Yakusho) is arrested for murdering, mutilating and burning his industrialist boss after being fired from his position and freely admits to the crime, it seems an open and shut case for defense attorney Shigemori (Fukuyama Masahuru), who is brought into the fold by senior associate Settsu (Kotaro Yoshida). But when Shigemori begins to look for ways to reduce his client’s sentence, he begins to see several inconsistencies which lead him to question the confession. When pressed, Misumi begins to change his story, claiming the wife of his dead boss hired him to kill her husband. But the dead man’s teenage daughter Sakie (Hirose Suzu) may have some information which sheds more light on the increasingly mysterious case. Meanwhile, Misumi’s past criminal record is important to the proceedings. Having murdered two loan sharks decades prior in Hokkaido (which is Shigemori’s hometown), Misumi avoided the death penalty thanks to the leniency of the judge, who happens to be Shigemori’s father (a man who once believed circumstances were the root of criminality, only to believe the exact opposite now). Little by little, Shigemori soon questions his own professional ambitions.

In the scheme of Kore-eda’s filmography, The Third Murder is akin to his 2009 Air Doll in its deliberation on discordant, adult themes. Incest and murder exist as dueling specters of a debate regarding nature vs. nurture in this melodrama which is curiously predicated on showing us the murderer before going through a series of backtracking resolutions which eventually casts what we thought we knew for certain into doubt. Less a courtroom drama than an investigative procedural, Kore-eda spends the prolonged set-up utilizing conversations to unveil extensive exposition regarding Misumi’s criminal history as well as differentiations in charges which will potentially reduce the sentence (another recurring thorn in Shigemori’s side as he is charged with being a certain type of meddlesome attorney). “You don’t need to understand or empathize to defend a client,” he professes to his other associates (who exchange a jovial banter similar to the occupational snippets of last year’s After the Storm).

As the crisply efficient Shigemori (played with a serene cool by Fukuyama Masaharu of Koreeda’s celebrated Like Father, Like Son, 2013) begins to become invested in the strange fluctuations in his client’s demeanor, what becomes an initial clear-cut strategy to change the charges from murder and burglary to murder and theft eventually reveals a professional undoing for the attorney.

For all the laborious deliberations on guilt and circumstance, it’s how Kore-eda’s usual DP Mikiya Takamoto slyly begins to collapse Shigemori and Misumi’s visual profiles until they are overlaid onto one another (at the same time, we become consumed by the reserved, steely palette up until a finale which seems even more striking for its inviting rays of sunlight). Likewise, the film features two young girls who eventually provide the gateway for both men, each harboring their own guilt for the daughter’s they’ve neglected due to professional or personal choice, and the surrogate promise of redemption via the emotionally compromised and physically crippled Sakie (returning from Kore-eda duty in his 2015 Our Little Sister). Her eventual predicament reveals Shigemori to share similar sentiments to Misumi, whose crime he eventually feels is justified. And here’s where The Third Murder (third time’s the charm, perhaps) begins to tighten its philosophical slipknot. Are there people who should have never been born as well as those who deserve death? And who, by right, should have the ability to judge them?

Notions of provocation leading to a certain sense of justification, as well the inevitable decency of a proper burial for all creatures great and small unites the thought processes of both men to reveal how easily it is to warp what begins as a rational sensibility. Tasked with defending the guilty and finding a loophole to either lessen or dismiss his client’s charges, Shigemori is de facto a player on the opposite side of the law, an apparent mentality long before his emotional investment. Approaching the murdered businessman’s family and their rejection of his client’s apology letter, he berates their coldness. “These days victims think they can get away with anything.”

As sharply observed as any subjects and characters Hirokazu Kore-eda gravitates towards (and sometimes bit too methodically so), The Third Murder attempts to examine the monstrous side of mankind, and how we’ve decided to explain, rationalize, or maybe even accept it.

Reviewed on September 8th at the 2017 Toronto International Film Festival – Masters Programme. 124 Mins

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆