The Workshop Around the Corner: Bing Threads Through Textile Manufacturing

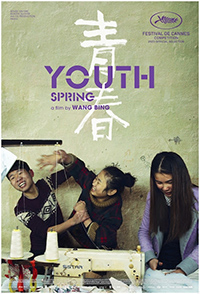

Having filmed from 2014 to 2019 in the city of Zhili, Youth (Spring), one of the latest projects from director Wang Bing, is potentially the first part of a forthcoming ten hour series. Those familiar with his style will recognize his practical methods of capturing life unfolding, even if this often means forging through elements both banal and potentially mundane, with this latest three-and-a-half-hour exercise being no exception. However, it’s also something of a refreshing departure for Bing considering the subject matter isn’t involving a laser focus on death and degradation. In fact, as its title suggests, there’s a certain jauntiness in the film’s energy as it follows a myriad of teenagers and young adults through their work routines and the intimacies of their daily grinds in bustling textile manufacturing hub. That’s not to say there isn’t a certain inevitable laboriousness in observing their endeavors, but it captures a sense of Sisyphean starkness in the reality of labor often ignored.

Having filmed from 2014 to 2019 in the city of Zhili, Youth (Spring), one of the latest projects from director Wang Bing, is potentially the first part of a forthcoming ten hour series. Those familiar with his style will recognize his practical methods of capturing life unfolding, even if this often means forging through elements both banal and potentially mundane, with this latest three-and-a-half-hour exercise being no exception. However, it’s also something of a refreshing departure for Bing considering the subject matter isn’t involving a laser focus on death and degradation. In fact, as its title suggests, there’s a certain jauntiness in the film’s energy as it follows a myriad of teenagers and young adults through their work routines and the intimacies of their daily grinds in bustling textile manufacturing hub. That’s not to say there isn’t a certain inevitable laboriousness in observing their endeavors, but it captures a sense of Sisyphean starkness in the reality of labor often ignored.

Not unlike his eight hour opus Dead Souls (2018), wherein aging survivors of Mao Zedong’s work camps from the 1950s and 1960s, were interviewed about their experiences (and many of whom died before the film premiered), Bing flashes introductions of his subjects across the screen, often including age and specific workshop location. Of course, we are fed some tidbits at the end regarding the 300,000 migrant workers filtering through Zhili, but the focus here is pared down in relation to the statistics. Instead we glean a series of recurring themes, including workers constantly trying to get paid their worth despite workshop owners trying to please consumers who are quick to proclaim a shop’s prices are too high.

Expectedly, there’s a constant drive to complete their output on time, and Bing focuses on the furious, fast-paced sewing they’ve become accustomed to. Shop talk often includes who’s the fastest of any given crew, and the film opens on a jovial competition between co-workers trying to out-sew one another. In some instances, more dire circumstances are percolating, such as a young woman waiting to schedule her abortion after a bevy of orders are filled.

But mistakes are also an inevitability, and bitter bickering occurs when complex orders have to be re-done. As a constant reminder, these young laborers often reveal their age through their behavior, the men vying for attention of the women, sometimes leading to questionable workplace behavior (although ‘harassment’ is laughingly acknowledged), with the women usually exerting control of the situations documented here. Bing captures a rather uncomfortable melee when some joking goes too far, leading to hurt feelings and tears when the shop owner has to step in to regulate.

More interesting, perhaps innately as a departure from the sterility of the manufacturing shops and their constant whirring, are Bing’s exploration of their living situations. Many are crammed into spaces resembling a hostel or dormitory, the workers are often packed into one living space. Though their sleeping places might be separated by gender, it appears they all often have to share the same washroom. This leads to a mixture of annoyance and potential flirtation. Eventually, we’re led to some of the more outspoken workers acting as bargaining agents for their colleagues, demanding higher wages and other compensations, to which the shop owner doesn’t necessarily have to be amenable. In the last portion of this documentary, one gets the sense a deal is easily procured potentially because the interaction is being filmed. Workers have the option of trying their hand in other shops, but this can be a dead end – one gets a reputation for being unreliable quite quickly, so it’s a profession which seems to suggest better the devil you know.

Although Bing’s fly-on-the-wall stance can be a bit grueling in one sitting, his scale and purpose are always impressive. It’s more palatable than the distressing Mrs. Fang (2017), where we slowly watch a woman wither away and die in less than satisfactory medical care conditions, but beneath the surface of its mostly cheerful participants, there’s a dark irony suggested by the title, where the bloom of youth is frittered away by a never ending struggle to survive in a machine designed to wear its parts down to nothing.

Reviewed on May 18th at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival – Competition. 212 Mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆