The Kids Are All Right: Barbosa Explores Brazil’s Class Fissures in Evenhanded Debut

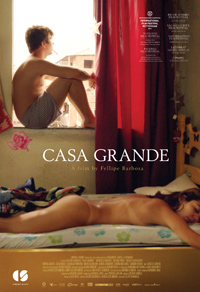

Familiar dramatic conflicts are elevated by strong performances and astute characterizations in Brazilian director Fellipe Barbosa’s directorial debut, Casa Grande. An exploration of significant class issues, a recurrent trope in many recent socially minded offerings from an increasingly exciting and prolific new generation of filmmakers in Brazil, Barbosa’s film premiered at the Rotterdam Film Festival about a year before Anna Muylaert’s Sundance debut, The Second Mother, a similar economically tinged drama from the perspective of the working class characters.

Familiar dramatic conflicts are elevated by strong performances and astute characterizations in Brazilian director Fellipe Barbosa’s directorial debut, Casa Grande. An exploration of significant class issues, a recurrent trope in many recent socially minded offerings from an increasingly exciting and prolific new generation of filmmakers in Brazil, Barbosa’s film premiered at the Rotterdam Film Festival about a year before Anna Muylaert’s Sundance debut, The Second Mother, a similar economically tinged drama from the perspective of the working class characters.

Barbosa captures the shameful downfall of a well-to-do white family on their initial descent into financial ruin as witnessed by their 17-year-old son as he grows from clueless, privileged teen to rebellious, outspoken personality who discovers how to speak for himself. Though its subject matter might seem a bit too by the book, especially when removed from a specific cultural context, Barbosa crafts compelling, authentic characters to hold your attention.

Hugo (Marcello Novaes) and Sonia (Suzana Pires) are an affluent couple living in an upscale suburban community of Rio de Janeiro. Ambivalent towards their teenage children Nathalie (Alice Melo) and Jean (Thales Cavalcanti), they can only manage superficial bouts of communication, which is exactly why the kids aren’t informed of their parents’ growing economic troubles. Initially, these money problems are imperceptible, and the paralyzed attitude of Hugo and Sonia would seem to indicate otherwise, even after the mysterious firing of their driver, which begins to cause a sort of unravelling for their son.

Unlike the juxtaposing, intersecting drama of Kleber Mendonca Filho’s 2012 hit Neighboring Sounds, the family at the heart of Casa Grande is defined by the economic symbol of the title, hunched up in privileged isolation in the suburbs of Rio. A group of women visiting Sonia hardly seem alarmed when the security alarm sounds at one point. “It’s always animals,” she calmly explains, “never people.” Besides exemplifying why the rich make such easy targets for criminal activity thanks to their ignorance and obliviousness to reality, it explains Jean’s rather delayed awakening to the faults of his parents, something his younger sister Nathalie already seems vehemently aware of.

Barbosa inflects much of the family’s intimate conversations with topical issues, such as the new government sanctions demanding a 40% quota of minorities within the country’s various institutions, an action accompanied by the general diatribes from a generally unchallenged majority.

And so, we witness Jean as he becomes attracted to all the ideals his laissez-faire family deems inappropriate. He regularly shares a bed with the maid, and the family’s firing of their driver forces Jean into public transportation to get back and forth from school, where he meets a mixed race young woman he becomes romantically involved with. It’s not so much Jean embraces an ‘urban’ sensibility, but finds he’s attracted to more tangible, authentic human connections than those stale motions enacted by his nuclear family.

In one darkly comic aside, Barbosa makes good on his depiction of a popular tactic wherein criminals call random homes demanding ransom for kids. During one of Jean’s escapades, Sonia receives such a call. Since she’s quite open to suggestion, she’s convinced she’s heard the voice of her son on the other line, even though the narrative makes it clear this is not the case.

Shot by Neighboring Sounds DoP Pedro Sotero, Casa Grande takes place almost completely in the safety and sterility of this nuclear family’s privileged zones, and its minor dramatic instances only tend to transpire whenever Hugo is forced to interact with the outside world. But Barbosa keeps all of this low-key and observational, even as he sets up a family’s economic meltdown usually accompanied by severe genre flourishes in films of similar subject matter. However, the film eventually settles gingerly into a coming-of-age vein which brings the finale to a somewhat touching moment of emotional fulfillment.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆