Reviews

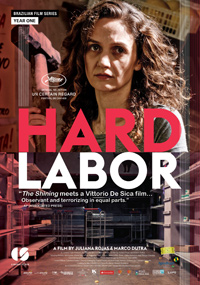

Hard Labor (Trabalhar Cansa) | Review

There’s a Ghost in Me: Dutra and Rojas Explore the Reductive State of Capitalism

The changing socioeconomic landscape in Brazil has had a direct impact on the burgeoning cinematic landscape as well. The country’s move into a capitalist economy has resulted in significant shifts, whether that is what defines a sense of neighborhood and community in recent offerings from Sergio Bianchi with The Tenants (2009) or Kleber Mendonca Filho’s Neighboring Sounds (2012) or the opportunities afforded members of the working class causing unavoidable fissures in traditional behaviors, like The Second Mother (2015). In Hard Labor, the directorial debut of Marco Dutra and Juliana Rojas, gender and class expectations are bungled in unexpected ways, where social upsets reveal the rotting infrastructure from within. Filled with allegorical instances, the striking debut unfolds with the delirious menace one would expect from a horror film, yet stays invested in the daily banalities of aching social reminders of limitations. With power and responsibility comes a certain paranoid terror, while the failure of fulfilling one’s obligations presents its own set of primordial backpedaling.

Just as Otavio (Marat Descartes) loses his white collar job, his wife Helena (Helena Albegaria) realizes her own dream as a business owner when she rents a dilapidated store front and revitalizes it as a neighborhood grocery. As Otavio trudges around to futile job interviews in a market that’s changed vastly since he was last forced to compete in it, Helena hires a working class maid, Paula (Naloana Lima) to look after their daughter. But Helena receives a rather chilly welcome from the locals, and strange things begin to happen, including a lack of knowledge concerning the whereabouts of the former tenants.

Hard Labor premiered in the 2011 Un Certain Regard sidebar at the Cannes Film Festival (Mexican director Everardo Valerio Gout’s Days of Grace also played in the fest’s lineup and just saw US theatrical release this year), and unfolds like the kind of insidious social commentary unleashed following a cultural release from a dreadful political regime. Everywhere we look we find evidence of foundations rotting from the inside out. Though the country may be coming into a new economic age, you can’t simply put another coat of paint on something and call it brand new.

Rights for the working class may be available, but as evidenced by Helena’s hiring of Paula ‘off the books’ (meaning she won’t have health benefits options or other expected frills) and her eventual treatment of the workers at her homegrown grocery store, it’s oftentimes only lip service. Playing around with gender roles as Helena overtakes the responsibilities of breadwinner, a changing social climate only seems to render opportunities for the middle-class white male obsolete, or at least that’s the message Dutra and Rojas instigate, a popular nightmare for the heteronormative within increasingly oversaturated job markets.

But as Dutra and Rojas make deliberate efforts to show the painstaking restructuring of Helena and Otavio’s lives, dreams quickly become nightmares. Kernels of something terrifying lurking on the periphery of their lives begins to nag at them, meanwhile enhancing our sense of unease. A vicious barking dog, strange animal remains, and a stinky seepage oozing up through the cracks on the floor of the grocery store doesn’t bode well for Helena’s business. As her curiosity gets the best of her, she takes a chisel to the wall and discovers something disturbing holed up inside, something that makes her store seem like it rests atop a gateway to hell.

Subtle, without ever breaking out into an onslaught, horror seems used more as a metaphor for society’s mutated ills, not too terribly unlike the cannibal family from Jorge Michel Grau’s We Are What We Are (2010). If anything, the struggling suburban family portrayed here feels like a prologue to something much direr. A howl of primitive rage sends us off into the credits, a final descent into the madness in store for those demoted to the lower depths. Weird and offbeat, it’s a film poised to aggravate due to a refusal to commit to clear cut explanations. But as Brazilian cinema continues to gain a stronghold in the Latin American market, perhaps inconspicuous items such as Hard Labor won’t struggle for years to secure theatrical release.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.