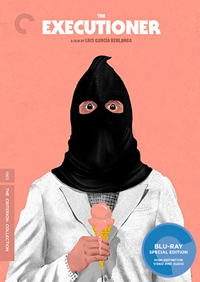

Aided by significant cultural and social subtexts, Luis Garcia Berlanga’s seminal 1963 film The Executioner is a black comedy delivering all the gallows’ humor its title promises. An examination of capital punishment as merely one aspect of the problematic, bureaucratic social maneuverings of a country still in the grip of Franco’s dictatorship, it’s one of the prolific filmmaker’s most ripe, notable works—and yet, as one of the most critically celebrated directors from Spain, his international renown is lodged (along with several others) under the formidable shadow of Luis Bunuel’s cinematic legacy (the scandalous reception of the 1961 Palme d’Or winning film Viridiana is also credited as another factor in the immediate disparagement of Berlanga’s title), while the execution of Spanish politician and Communist party leader Julian Grimau Garcia in April of 1963 also put pressure on Francoist Spain to denounce Berlanga’s topical treatment. Premiering out of the 1963 Venice Film Festival, Berlanga won the FIPRESCI prize, and the film was critically embraced upon a US release in 1965 (under the title Not On Your Life). In Spain, the film was regarded as communist and bolstered the continual interference of the censors thwarting Berlanga’s films, and it would take four years to mount his next effort, Las Piranas (aka La Boutique), which would film in Argentina.

Aided by significant cultural and social subtexts, Luis Garcia Berlanga’s seminal 1963 film The Executioner is a black comedy delivering all the gallows’ humor its title promises. An examination of capital punishment as merely one aspect of the problematic, bureaucratic social maneuverings of a country still in the grip of Franco’s dictatorship, it’s one of the prolific filmmaker’s most ripe, notable works—and yet, as one of the most critically celebrated directors from Spain, his international renown is lodged (along with several others) under the formidable shadow of Luis Bunuel’s cinematic legacy (the scandalous reception of the 1961 Palme d’Or winning film Viridiana is also credited as another factor in the immediate disparagement of Berlanga’s title), while the execution of Spanish politician and Communist party leader Julian Grimau Garcia in April of 1963 also put pressure on Francoist Spain to denounce Berlanga’s topical treatment. Premiering out of the 1963 Venice Film Festival, Berlanga won the FIPRESCI prize, and the film was critically embraced upon a US release in 1965 (under the title Not On Your Life). In Spain, the film was regarded as communist and bolstered the continual interference of the censors thwarting Berlanga’s films, and it would take four years to mount his next effort, Las Piranas (aka La Boutique), which would film in Argentina.

Amadeo (Jose Isbert), an aging executioner in early 1960s Spain, finds himself at the end of his career without a successor. This isn’t much of a surprise since his profession isn’t a popular one, but because he’s nearing retirement, his government allotted apartment will soon be taken away from him, where he lives with his beautiful daughter Carmen (Emma Penella). Because of her father’s profession, suitors for Carmen are few and far between, so they’re both equally delighted when Jose (Nino Manfredi), a handsome young apprentice to the local undertaker, walks into their lives by coincidence. Reluctantly, he is drawn into Amadeo and Carmen’s small circle, and is forced into one innocent concession after another, including marriage, eventually agreeing to replace his father-in-law as the executioner so they may keep their apartment. But when push comes to shove, Jose is convinced he’s not the man for the job.

Berlanga’s The Executioner isn’t too dissimilar from another dark farce recently restored by Criterion, Nagisa Oshima’s 1968 title Death by Hanging, wherein Japanese authorities bungle the execution of a Korean immigrant. Berlanga is more interested in how social cues are executed as a complicated series of traps for people, skirting around a scenario which hinges on the Kafkaesque, providing us with a perspective of an executioner as another victim of circumstance. The scenario is one of seven collaborations with Berlanga’s longtime screenwriter Rafael Azcona and stars admired character actor Jose Isbert (he would pass away at the age of 80 three years later in 1966) as the elderly executioner, who had previously appeared in Berlanga’s award winning Welcome, Mr. Marshall! (1953), a film famously derided as anti-American by Edward G. Robinson at the Cannes Film Festival. Isbert’s Amadeo is the wily manipulator of the film (confirmed magnificently in the film’s closing moments), and one gets the sense, as his successor, Manfredi will eventually be assuming the same characteristics.

The effortlessly entertaining but increasingly macabre plot clips along rather quickly. Amadeo’s griping about how his profession was once appreciated, even admired by his ‘clients,’ begins the narrative’s cultural critiques—not only are the condemned resentful of their sentence, but no one can seem to appreciate Spain’s humane use of the garrote. “The Americans are worse with their electric chairs,” he spits, commiserating with Nino Manfredi’s apprentice undertaker on the hearse back to town after his latest kill. Of course, his fate is sealed upon meeting his beautiful daughter, played by Emma Penella, a young woman eager for interaction since most men are turned away by her father’s profession, a perfect fit for Jose, who can relate to this predicament. But carnal knowledge leads to his ultimate undoing—and not because his union with Carmen has resulted in the making of a new life, but to save his own. Amadeo is capable of killing, as Carmen reminds Jose when he asks why she informs her father of their misdeed.

Manfredi would receive international renown in the 1970s thanks to items like Bread and Chocolate (1974), but the young actor proves to be quite adept at playing a passive schlep here (and predates another early role in Pietrangeli’s I Knew Her Well, 1965). The conflict culminates in the film’s best sequence, wherein a clergyman is forced to counsel the newly appointed executioner and his first victim, while both men are dragged unwillingly to the site of execution. But Berlanga’s film contains many subtle critiques, including a rather flippant aside where a woman approaches a bookstore owner to see if he has anything on Bergman or Antonioni (ironically, both those auteurs would pass away on July 30, 2007). “Bergman the actress?” he asks. “Nevermind,” says the woman, walking on.

Disc Review:

Criterion presents the film with a newly restored 4K digital transfer from the original 35mm camera negative, with uncompressed monaural soundtrack, presented in the original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. Picture and sound quality are superb, and it’s a beautiful example of masterful DP Tonino Delli Colli (Salo; Death and the Maiden; Life is Beautiful), culminating in a chilling longshot where Manfredi is dragged into the death chamber, his white hat symbolically left behind in the stark, outer chamber, a semblance of his civilized identity literally checked at the door. Several notable extra features, including a new interview with Pedro Almodovar, are included.

Pedro Almodovar:

In this brief four minute interview recorded in 2016, director Pedro Almodovar explains why The Executioner is one of his favorite movies, claiming all of Spanish cinema is derived from Bunuel and Berlanga (he credits part of the reason Berlanga is less well known outside of Spain is the impossibility of subtitling his group sequences, with usually five or six characters in the frame talking—which would be akin to subtitling Robert Altman for non-English language speakers).

Bad Spaniard:

A new hour long documentary profiles Berlanga and his essence, offering an analysis of The Executioner through interviews with his son Jose Luis Berlanga, critic Carlos F. Heredero (who credits him with accentuating the grotesque), writers Fernando R. Lafuente and Bernardo Sanchez Salas, and Rafael Maluenda, director of the Berlanga Film Museum.

La Mitad Invisible:

A 2009 episode of the television program “La Mitad Insivisble” explores why Berlanga’s The Executioner is one of the most beloved films in Spanish cinema (which aired a year prior to the auteur’s death).

Final Thoughts:

Criterion’s resurrection of Berlanga’s celebrated title should result in a renewed interest in his extensive, politically minded filmography, but The Executioner is certainly a hidden gem for lovers of morbid, grotesque social comedies.

Film Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review:★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆