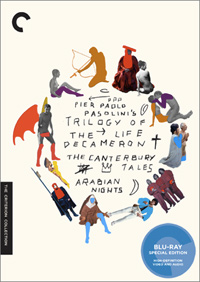

His life tragically and brutally cut short by a still unknown assassin, Italian auteur Pier Paolo Pasolini’s last completed project, known as the Trilogy of Life, gets the master treatment from Criterion this month, which includes three films based on classic literary anthologies, The Decameron (1971), The Canterbury Tales (1972), and Arabian Nights (1975). Pasolini was one third done with his next project, to be called the Trilogy of Death, of which his last film, Salo (1975), was the first installment. Upon each of their initial releases, the Life films were all equally greeted with controversy, celebration, and a distinct notoriety, but all overshadowed by the infamy of Salo, which stands on many lists as one of the most difficult to watch films of all time (and was the first Pasolini title to be inducted into Criterion’s annals). Pasolini’s overall motif encapsulated in these three features is a celebration of life, a recalcitrant joyousness in the pre-modernized world, juxtaposing vulgarity and piety, the sacred and profane.

His life tragically and brutally cut short by a still unknown assassin, Italian auteur Pier Paolo Pasolini’s last completed project, known as the Trilogy of Life, gets the master treatment from Criterion this month, which includes three films based on classic literary anthologies, The Decameron (1971), The Canterbury Tales (1972), and Arabian Nights (1975). Pasolini was one third done with his next project, to be called the Trilogy of Death, of which his last film, Salo (1975), was the first installment. Upon each of their initial releases, the Life films were all equally greeted with controversy, celebration, and a distinct notoriety, but all overshadowed by the infamy of Salo, which stands on many lists as one of the most difficult to watch films of all time (and was the first Pasolini title to be inducted into Criterion’s annals). Pasolini’s overall motif encapsulated in these three features is a celebration of life, a recalcitrant joyousness in the pre-modernized world, juxtaposing vulgarity and piety, the sacred and profane.

The first of the trilogy is an adaptation of nine tales from Boccaccio’s 14th century work, The Decameron (which was comprised of a hundred tales, spanning a time frame of ten days, as indicated by the title, a framework abandoned here), each tale picked, it seems, for its advanced erotic content. Framed by a tale of a con artist, Ciappelletto (Pasolini regular Franco Citti, appearing in all three films), who pops up intermittently in the first half of the film, only to fool a priest on his deathbed, we’re ushered swiftly into a revolving door of characters that harpoon religious dogmas and explore ribald sexual liaisons. There’s Andreuccio of Perugia (Ninetto Davoli, also appearing in all three films), swindled out of his money in an elaborate con by a woman posing as his half sister, quickly falls (besides a literal cess pool) in with a group of robbers, only to be swindled again. A man poses as a deaf mute in a cloister of sexually repressed nuns, only to become their sexual relief; a woman tricks her husband into cleaning out a giant clay vase while she’s ravaged by her lover; three brothers murder their sister’s lower class lover, only to see her unearth the body and place his head in a potted plant of basil to be watered by her tears; a young girl concocts a plan to let her parents sleep on the rooftop so her young lover can sleep with her; a perverted priest fools a farmer into copulating with his wife as he pretends to transform her into a donkey; two friends try to discover what happens after death; and Pasolini himself appears a Allevio di Giotto, a painter that inspires a team to create a church mural. During the second half of the feature, Pasolini also recreates live action representations of several Giotto paintings, where Sylvana Mangano makes an appearance as the Virgin Mary in place of Christ. The films ends with Pasolini pointedly musing, “Why complete a work when it’s so beautiful just to dream it?”

The second film, based on Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales stars Pasolini as the author, and it’s framed amongst a group of Pilgrims making a journey to Canterbury, each telling a tale to pass the time. Here we get eight separate tales, beginning with the Merchant’s tale, concerning a young woman (Josephine Chaplin, daughter of Charlie) who marries a horny old man, but when he is blinded, she boldly continues her flagrant indiscretions with her lover. Then there’s the Friar’s tale, concerning homosexual blackmail, and then Franco Citti returns as the devil, who comes to witness human misery; three young boys discover a treasure and turn on each other; a wife and her lover trick her husband into hiding himself away to prepare for the next great flood while they copulate, only to be interrupted by her other lover; Ninetto Davoli returns as a mischievous adolescent in an ode to Chaplin’s silent cinema; the Wife of Bath sends several husbands to death with her sexual appetite, until she meets a match of sorts; two young scholars approach a farmer that’s been robbing their grain, only to bed his wife and daughter; and then there’s the show stopping final sequence where an angel takes a friar to hell to witness what happens to friars that get sent there.

The last film, Arabian Nights focuses, again, on the erotic tales from the collection, creating a landscape of sexual explorations across Africa, Nepal, and the Middle East. The film is framed by a young man, Nur Ed Din (Franco Merli) who comes in possession of a young slave girl, Zumurrud (Ines Pellegrini) who gets to choose him as her master. When they are separated, Nur Ed does all he can to be reunited with his love, who escapes the clutches of her abductors, and, posing as a man, manages to become the king of a nearby city. The narrative structure of Arabian Nights becomes even less cohesive, and we’re treated to a whirling cascade of separate storylines, ranging from Franco Citti, here a red haired demon with a princess tucked away in isolation; Ninetto Davoli as a man named Aziz, engaged to his cousin Aziza, only to fall in love at the last minute with a seductive woman who throws a cloth at him from her window, and we find him relating his story to Taj (Francesco Paolo Governale), a wandering desert prince. There’s stories framed within stories, and more overtly violent sequences (including a castration scene), while also managing to be the most sexually free of the three films.

Disc Review:

Criterion’s digital restorations of the three Pasolini titles makes for the best way possible to experience these sumptuously photographed pieces of art. Pasolini’s work has been described as the cinema of poetry, and between the decadent art direction and multifaceted storylines, there’s a barrage of imagery and content that demands multiple viewings. For the uninitiated, this trilogy is perhaps the lightest introduction to an auteur fascinated with the darker and depraved elements of human existence. As far as extras go, Criterion has outdone themselves with superb visual essays and documentaries on each disc, featuring expert background about each film production, which only serve to enhance the viewing experience. Pasolini was described and denounced as a naïve realist, which also serves as criticism of how many of his films looked, though Tonino Delli Colli’s lavish photography on display here would hardly seem to warrant such dismissal. There’s breathtaking shot compositions, brimming with varied on screen action and visually jarring moments, such as a close up on Mangano’s stunning Virgin Mary that leap off the screen. The sound mix is exemplary, and for the hardcore junkies, Criterion includes the Pasolini approved English dubbed version of The Canterbury Tales.

Extra Features: The Decameron

On “The Decameron”

A visual essay by film scholar Patrick Rumble discusses the carnivalesque celebration of the film, and Pasolini’s confusing presence as a gay Catholic Marxist artist. Rumble discusses Pasolini’s working relationship with Fellini (he would be involved with Nights of Cabiria and La Dolce Vita) which ended after Fellini apparently didn’t care for Pasolini’s style on his 1961 directorial debut, Accattone. Rumbles goes on to cite The Decameron as the most political film Pasolini ever made.

The Lost Body of Alibech

A forty-five minute documentary from 2005 by Roberto Chiesi explains a lost sequence from The Decameron, excised by Pasolini at the last minute before the film’s premiere at the Berlin Film Festival. The sequence is recreated with the script and production stills.

Via Pasolini

A twenty-seven minute documentary from 2005 featuring archival footage of Pasolini as he discusses his views on language, film, and modern society. We learn of his tempered, dramatic relationship with his father, and how every time an artist opens his mouth, he commits an act of protest. When asked what type of people he loves in an interview, Pasolini explains that he loves simple people, those that have not become empty words, a type of lucidity only found there or amongst a very high level of culture. The documentary ends with news footage from when his corpse was found.

Trailers

The original theatrical trailer, marketing the film as a bawdy, outrageous new film from the infamous director.

Extra Features: The Canterbury Tales

Interview with Sam Rohdie

An interview with film scholar Sam Rohdie discusses how the Friar’s tale is not exploring homophobia but issues of money, and claims that Pasolini’s citations are art and literature and not the history of cinema. Pasolini, with this trilogy, favors a structure of gags over narrative.

Pasolini and the Secret Humiliation of Chaucer

This 2006 documentary by Roberto Chiesi discusses Pasolini’s frame of mind during the making of this feature, a film which is described here as “common to the point of being degrading.” Apparently, Pasolini’s muse, Ninetto Davoli, who had been in a relationship with the director since he was 15 years old, had left the director for a woman, ending a 9 year relationship. Going through a significant depression, Pasolini had a hard time continuing with this trilogy meant to celebrate life. Clips and materials are included in this 47 minute documentary that discuss Pasolini’s take on this film, which he considered metalinguistic, a “a film about film.” One particular cut sequence, involving the tale of Sir Thorpas, told by Chaucer himself, is fleshed out with production stills and transcripts from the original script.

2012 Ennio Morricone Interview

This 2012 interview with composer Ennio Morricone, who scored Pasolini’s films from The Hawks and the Sparrows (1966) going forward, discusses Pasolini’s innate professionalism, though Morricone admits that by the time of the trilogy, he was simply doing as Pasolini dictated.

2012 Dante Ferretti Interview

This 2012 interview, also for Criterion, with art director Ferretti, reveals many of the same details about Pasolini’s working behavior as Morricone—he was a professional that never used informal address with his colleagues. Ferretti discusses the artwork of Giotto (who Pasolini portrays in The Decameron), and how his work influenced the design of that film.

Extra Features: The Canterbury Tales

Introduction by Pasolini

Arabian Nights premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1974, and this footage shows Pasolini at the fest, fielding questions about his inspiration for the film, how he chose stories that seemed the most beautiful from his memories as a child.

On “Arabian Nights”

Film scholar Tony Rayns discusses how the trilogy represents Pasolini’s attempt to be positive for the first time in his life. Interestingly, Rayns discusses the involvement of Ninetto Davoli here, as the film serves as Pasolini’s farewell to the actor, who left him the year before. For the first time Davoli is featured nude in one of Pasolini’s films, and the story he appears in bears similarities to their real life relationship (not to mention he undergoes the film’s most brutal act of violence).

Deleted Scenes

Several deleted scenes are included, accompanied by transcriptions from the original script.

Pasolini and the Form of the City

A sixteen minute documentary from 1974 shows Pasolini and Paolo Brunatto discussing the cities of Orte and Sabaudia, and how Pasolini chose them for their perfection and style as a way to dictate a film.

Final Thoughts:

Ever the controversial provocateur, Pasolini’s work, even this carnivalesque celebration of life, remains divisive, amazing, and timeless. Devoid of linear narrative structure, all three of these films are really more of a merry-go-round of human experiences with sexuality, religion, life, and death. Certainly, these represent a departure from his previous filmography, and Criterion includes as part of the set, a 1975 “abjuration” of the trilogy published by Pasolini, where he writes, “I reject my Trilogy of Life, although I do not regret having made it.” His last film, Salo, would see him returning to the degradation of humanity with a fierce vengeance. While his Life trilogy can be glossed over as simplistic, hedonistic explorations of the human experience, they exist as the product of a genius at his most positive, his intentions tempered and crumbling even as he created them. They’re light, entertaining, and beautiful to behold, like paintings in motion, and feature one of the most stunningly bombastic sequences of cinema at the end of The Canterbury Tales where Pasolini gives us a portrait of hell, a rocky, smoking terrain, where the hypocritical holy are sent to be shit out of the devil’s bright red ass (literally). Criterion brings us this amazing trilogy to a new, beautiful restoration, and thankfully includes a dense amount of special features material to wade through.