Last Train to Zhili: Bing Brings Youth Cycle to Circular Close

Wang Bing completes his ‘Youth’ trilogy with finale Youth (Homecoming), which features the most forgiving running time of the three segments at only two and a half hours. The Cannes premiered Youth (Spring) (read review) was an hour longer and Youth (Hard Times) (read review), which premiered several weeks earlier at the 2024 Locarno Film Festival, clocked in at nearly four hours. The entire project was shot between 2014 to 2019, mostly in China’s Zhili province, home to a multitude of garment workshops. The final chapter appropriately begins with some 2014 footage and ends in 2019, but most of its integral moments transpire at the end of 2015 and into the 2016 Chinese New Year. The subtitle of the finale is most certainly meant to be ironic, its subjects trapped between two ‘homes,’ the furious hamster wheel of the city and their remote hometowns, with families they are expected to support and return to on the annual national holiday.

Wang Bing completes his ‘Youth’ trilogy with finale Youth (Homecoming), which features the most forgiving running time of the three segments at only two and a half hours. The Cannes premiered Youth (Spring) (read review) was an hour longer and Youth (Hard Times) (read review), which premiered several weeks earlier at the 2024 Locarno Film Festival, clocked in at nearly four hours. The entire project was shot between 2014 to 2019, mostly in China’s Zhili province, home to a multitude of garment workshops. The final chapter appropriately begins with some 2014 footage and ends in 2019, but most of its integral moments transpire at the end of 2015 and into the 2016 Chinese New Year. The subtitle of the finale is most certainly meant to be ironic, its subjects trapped between two ‘homes,’ the furious hamster wheel of the city and their remote hometowns, with families they are expected to support and return to on the annual national holiday.

Bing’s trilogy presents a novel opportunity to observe rituals and behaviors under impossibly dysfunctional conditions, now from the vantage of a time capsule but without a sense much has changed in any positive regard. The spirit of this film is more akin to Spring, where opening footage in the factories conveys teens and twentysomethings dependent upon relationships fostered through propinquity, both romantic and otherwise. A handful of scenes in woefully unkempt bedrooms and living spaces find these youths in high spirits (as opposed to Hard Times, which delved much more into the dark side of lost wages, a dwindling industry, and intensifying, difficult working conditions).

In his somewhat meandering way, Bing focuses on a handful of subjects, though many more are featured. The 2014 opening introduces us to Shi Wei, reduced to muttering a phrase he’s likely repeated often, “Where there’s work, there’s life.” We return to Shi Wei two years later during his wedding celebration, one of the few purely entertaining segments across the entire trilogy.

A major portion of Homecoming focuses on a couple, Mu Fei and Dong Mingyan, leaving Zhili during Chinese New Year in 2016 to visit their parents, who live in relative proximity to each other. A cram packed train leads to a treacherous drive up mountainous dirt roads to arrive at Ludian District in Yunnan Province. Both families meet their children with relative enthusiasm, but an aside from Dong finds her contemplating how they’re supposed to make a future with her current working conditions. Eventually, her parents won’t be able to support themselves, and her work expectations don’t allow for physical assistance. Likewise, Mu’s father is upset his son couldn’t have arrived when he needed assistance with some bricklaying. The delayed visit has allowed many of the bricks to be stolen.

A later pair of characters include Fang Lingping and her boyfriend, who have a rather interesting relationship. He gaslights her about an aging face thanks to too much smiling, while she’s frustrated with his inability to properly sew. And then there’s Chen Quangtao, a young man who seems to exist in the shadow of an older sister (and doesn’t know how to chew with his mouth closed). As the holidays end, Bing sails back to the doldrums of Zhili. And yes, they’ve escaped the muddy roads, tuberculosis, and isolation, but they return to the drudgery of endless humming machines. Bing includes a brief stint in 2018 and then, fittingly, ends with the same holiday in 2019. If home is where the heart is, it isn’t clear if it’s a state of being actually reflected anywhere in these lengthy passages of time occupied by employment which will barely allow its workers to cover the cost of living. They exist in a place where there is no life without work, and their only option is to work until they’re been worn down to incapacitation.

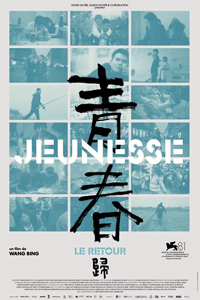

Reviewed on September 6th at the 2024 Venice Film Festival (81st edition) – In Competition section. 152 Minutes.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆