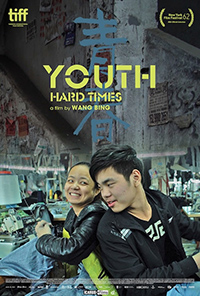

Make the Best of Us: Bing’s ‘Youth’ Cycle Expands Into the Gloom

The middle part of Wang Bing’s Youth trilogy, Youth (Hard Times) perhaps more properly addresses the bleak realities of his observational endeavor, cobbled together into a cohesive structure from footage shot between 2014 and 2019. Following the Cannes premiered 2023 film Youth (Spring) (read review), which felt a rather cynical moniker for subjects tethered to Sisyphean work routines in their prime, his second installment, which appears to be more systematically edited into a time frame from 2015, suggests a more blatant, world weary scope. At a running time of nearly four hours, its immersive, repetitive structure, while inherently Bing’s signature, feels more punishing if only because there’s no real room for levity in its lengthy, often grueling discourse of late teens and twenty-somethings struggling to make ends meet in thankless textile shops.

The middle part of Wang Bing’s Youth trilogy, Youth (Hard Times) perhaps more properly addresses the bleak realities of his observational endeavor, cobbled together into a cohesive structure from footage shot between 2014 and 2019. Following the Cannes premiered 2023 film Youth (Spring) (read review), which felt a rather cynical moniker for subjects tethered to Sisyphean work routines in their prime, his second installment, which appears to be more systematically edited into a time frame from 2015, suggests a more blatant, world weary scope. At a running time of nearly four hours, its immersive, repetitive structure, while inherently Bing’s signature, feels more punishing if only because there’s no real room for levity in its lengthy, often grueling discourse of late teens and twenty-somethings struggling to make ends meet in thankless textile shops.

Returning to Zhili, a province where seasonal migrant workers descend into workshops which each seem to have their own idiosyncratic rules and hierarchies, Bing’s continuation taps immediately into a collective anxiety. The common thread amongst these shards of narratives finds a growing practice where corrupt workshop owners finagle ways out of paying their employees. An early agonizing chapter finds a young man at a loss for collecting his wages because he’s unable to produce the paybook demanded by his current employer, even though he has a picture of it. Through a series of conversations, his pleas are to no avail.

Another increasingly common practice witnessed is the abandonment of the staff by workshop owners, who, unable to pay delayed wages, simply disappear. Law enforcement doesn’t see such complaints as a priority, and so, the unlucky employees go unpaid, salvaging whatever materials they can from the equipment left behind (though usually to wary buyers who have their own profiteering scam).

As we watch these young men and women work, a pattern develops as they endlessly barter for locked-in rates regarding whatever materials they’re completing. Those who are speediest seem the best positioned, but their conversations are almost constantly consumed by comparing how much they earn for what kind of work. Not surprisingly, many of the young women seem to receive the worst pay for their output. A main refrain is “we earn enough to live,” and, it would seem not even that much for many of the young people who are expected to send money back home to assist their families. While there are brief moments of cute flirtation and, again, even some singing, these are far more fleeting than more generous moments of levity in Youth (Spring).

Bing, who often spends many years observing communities and gathering footage, tends to highlight both historical miseries, as in the exceptional Dead Souls (2018), where survivors of Mao Zedong’s workcamps relay their experiences, and contemporary ones, like witnessing a woman’s slow death in Madame Fang (2017). While the cryptically titled third chapter, Youth (Homecoming) awaits, it would seem there is not a better title than the Dickensian Youth (Hard Times), which may be presenting the same, long-winded information over and over again, but then, how else could we possibly relate to how deadening these realities can be?

Reviewed on August 13th at the 2024 Locarno Film Festival (77th edition) — Concorso Internazionale section. 227 Mins.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆