Shohei Imamura’s brutalist depiction of female resilience in his masterwork of 1963, The Insect Woman, echoes the beloved French filmmaker Marcel L’Herbier‘s monumental silent avant-garde narrative L’inhumaine, which translates to The Inhuman Woman, in both name and loosely, in theme. Centering its Frankensteinian tale of high class love, loss and reanimation around a hardened woman of the world whose apathy toward men of all classes guides her way through parties and performances, L’Herbier’s brilliant collaboration with fellow art deco artists like the painter Fernand Léger, the architect Robert Mallet-Stevens, and soon-to-be-filmmakers themselves, designers Alberto Cavalcanti and Claude Autant-Lara, is nothing short of a cinematic masterpiece of modern invention.

Making use of a beautiful and thrilling combination of highly stylized studio sets and on location shoots on the outskirts of Paris, L’inhumaine trains its often matted eye on the famed singer Claire (real life opera star Georgette Leblanc, playing here a deliciously cold hearted queen bee) as she courts royalty and rich bachelors alike with a stupendous sense of passivity, clearly stating early on that she has grown bored with humanity and now is solely interested in ‘higher beings.’ After being pursued by and subsequently rejected a boyish inventor named Einar, in an immensely expressive sequence of visual anxiety the innovator hops in his sports car and (seemingly) drives off a cliff to his death, cuing Claire to reflect on her apathy and us to ponder the quandaries of memorial pomp and revelry.

To our gleeful surprise, when Claire is summoned to identify the body, it is revealed that Einar has faked his own death in a ploy to draw his love interest into his industrialized abode where he can win her over with the mystical power of technological advances. Anticipating the flat screen television by nearly 80 years while riffing on the mechanical aesthetics of Vertov and the shadowy, angular design of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Einar’s workshop boasts of reverse live video broadcasts, and of special interest to Claire, a device that reverses death (a god-like power, possible proof of being a ‘higher being’). In the climatic final sequence during which Claire is poisoned by a jealous suitor and subsequently risen from the dead by her scientifically inclined Frankensteinian lover, L’Herbier amps up the emotional expressionism with the use of color tints (red for anger, green for jealousy, etc.), kinetic, early deep focus camera work, image overlays and increasingly Eisensteinian editing – a formidably flamboyant montage of circuitry, craftsman, visual eloquence and narrative tension that’s accentuated by both of the magnificent new scores composed by percussionist Aidje Tafial and the Alloy Orchestra.

Despite all its technical invention and stylistic foresight (the massively influential International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts in Paris, at which he was a jury member, was just a year from opening), L’Herbier’s L’inhumaine became a massive fiscal failure upon its release in November of 1924, putting great financial strain on the filmmaker’s relatively new production company Cinégraphic as it prepared for his next two productions, Feu Mathias Pascal (The Living Dead Man) and Le vertige, both released in 1926. Yet, as a cinematic achievement it remains a pillar of wild stylistic experimentation within a straightforward narrative construction, perfectly suited, as L’Herbier had originally intended, to bring high art and populist enjoyment together for a sweet embrace of serine movie magic.

Disc Review:

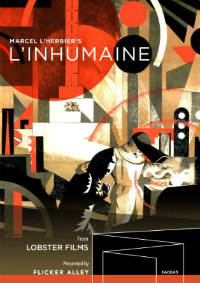

Having utilized the original nitrate negative, this brand-new restoration by Lobster Films not only exudes an astonishing amount of clarity and detail, but for the first time, also retains the dramatically infused tints of the original release. Supplemented with two stellar new scores, a fantastic electro jazz score from percussionist Aidje Tafial and the other, more traditional but no less enjoyable, by the Alloy Orchestra – both presented in uncompressed stereo tracks for fantastic fidelity. And to Flicker Alley has wrapped this lovely packaged in a classy clear case topped with some absolutely gorgeous nostalgically infused modernist artwork by Roam Creative.

Behind the Scenes of L’Inhumaine

Based on the ideas of Mireille Beaulieu, directed by Antoine Angé, and presented in French, this short visual essay explores where L’Herbier’s unique vision was born and how much his film forshadowed the coming art deco explosion that followed in its wake. 15 min

About the Recording of Aidje Tafial’s Music

Always a welcome extra, especially when involving newly composed pieces for silent film classics, this piece explores how Tafial composed his new score, where the instrumental decisions were made and witnesses the actual recording of the record in highly compressed time, highlighting just the most critical musical moments in the film. 18 min

Booklet

Featuring notes on the restoration and transfer, rare on-set production photos and Marcel L’Herbier’s filmography, this leaflet is centered around a lovely contextualizing essay on the film by Mireille Beaulieu, translated by Fabrice Zagury.

Final Thoughts:

The quintessential French auteur, Marcel L’Herbier was not only the director, but also served as screenwriter, editing supervisor, graphic designer, music supervisor and advertising supervisor on L’Inhumaine, forging ahead with a collaborative, but authoritative vision. Having had a phenomenal year of releases last year with their Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970 and Chaplin’s Essanay Comedies sets among others last year, Flicker Alley is on a red hot streak, continuing their exquisitely restored classic releases with yet another must have for silent film fans.

Film: ★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆