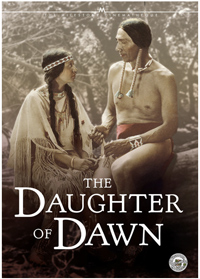

The story concerning the restoration of lost silent film The Daughter of Dawn (1920) nearly eclipses what amounts to as a fascinating achievement of its own merit. Much like the silent film production of Salome (1922), starring Nazimova, which professed to have been made by an entirely queer cast and crew, silent actor turned director Norbert Myles mounted this production consisting of an all-Native American cast (300 Kiowa and Comanche) who used their own homes and belongings for the on location shoot in the Wichita Mountains of Oklahoma. Shown once theatrically in Los Angeles in 1920, along with a couple of theaters in other cities, the title was never commercially released and fell into obscurity, considered a lost title for ninety years. But restoration began in 2005 after a nitrate print was located, which had fallen into the hands of a private detective who received it as payment for services rendered.

The story concerning the restoration of lost silent film The Daughter of Dawn (1920) nearly eclipses what amounts to as a fascinating achievement of its own merit. Much like the silent film production of Salome (1922), starring Nazimova, which professed to have been made by an entirely queer cast and crew, silent actor turned director Norbert Myles mounted this production consisting of an all-Native American cast (300 Kiowa and Comanche) who used their own homes and belongings for the on location shoot in the Wichita Mountains of Oklahoma. Shown once theatrically in Los Angeles in 1920, along with a couple of theaters in other cities, the title was never commercially released and fell into obscurity, considered a lost title for ninety years. But restoration began in 2005 after a nitrate print was located, which had fallen into the hands of a private detective who received it as payment for services rendered.

Simply, The Daughter of Dawn depicts a rather distressed love triangle concerning the titular princess (Esther LeBarre), the daughter of a Kiowa hunting chief (Hunting Horse), who requires her father’s consent before accepting a marriage offer. It just so happens two suitors come knocking at the same time, including Black Wolf (Jack Sankey-Doty), the more lucrative option to her father because he has a lot of ponies he can offer in exchange. But she loves White Eagle (White Parker), who only has his love to offer in return. Since her father doesn’t want to completely overlook his daughter’s wishes, he demands the rival suitors jump off a cliff, Medicine Bluff, and whoever survives wins her hand. At the deciding moment, White Eagle jumps and his injured while Black Wolf loses his nerve and his therefore banished from the tribe for cowardice. Another Kiowa maiden, Red Wing (Wanada Parker) has feelings for him, joining him in his exile, which is short-lived because Black Wolf links up with the enemy Comanche tribe and convinces them to go and steal the Kiowa women.

The Daughter of Dawn was certainly not the first title in the silent era to sport an all-Native American cast, and is pre-dated by 1914’s In the Land of the Headhunters (the oldest surviving film print from Canada). Writer Richard E. Banks reportedly spent twenty-five years living with various tribes, which accounts for the film’s maintained aim of accuracy. But the continued restoration of lost titles such as this revives the forgotten tidbits of diversity from the seventh art’s infancy, and these early chapters of Native Americans provide a stark contrast from other lost titles from more contemporary climes (like the recently restored The Exiles, Kent MacKenzie’s 1961 portrait of displaced Native Americans in Los Angeles).

Norbert Myles, who began as a silent film actor, would only direct two more features in the 1920s (Walloping Wallace; Faithful Wives) before working exclusively in make-up (he was responsible for Roy Bolger in 1939’s The Wizard of Oz), which is disappointing considering his achievement here. Although its dramatic thrust isn’t exactly significant, its portrait of Comanche, and particularly Kiowa cultural, is fascinating to behold.

Disc Review:

Milestone, commendably resurrecting historical and contemporary (Losing Ground) titles worthy of reconsideration and relevance in the cinematic canon, presents the title in 1.33:1. Restored by The Oklahoma Historical Society, the film receives a brand new orchestral score (from David Yeagley), since the original was not completed, and picture quality is quite impressive considering how many decades the print has languished. Several bonus documentaries produced by The Oklahoma Historical Society are included.

Introduction:

Dr. Bob Blackburn of the Oklahoma Historical Society introduces the film, speaking at the local filming site.

Finding the Film:

Bill Moore of the Oklahoma Historical Society discusses the film and how rare a find it is, detailing how it was found and brought to the Society in this six minute segment.

Heritage:

Darren Twohatchet, a video producer, is half Kiowa and Comanche and speaks on learning of the film, along with clips of several women who had memories or anecdotes on the film.

Heritage:

Dorothy Whitehorse, a Kiowa Indian, speaks of her girlhood and heritage in this six minute segment.

Magdalena Becker:

William D. Welge from the Oklahoma Historical Society speaks on missionary Magdalena Becker, assigned to a mission in Oklahoma among the Comanches in this three minute segment.

The Music Score:

Three separate individuals (Mark Parker, Benjamin Nilles, and John Cross) speak about the development of the orchestral score from the Oklahoma City University School of Music and Oklahoma City University Symphony.

Final Thoughts:

An unexpectedly interesting find, The Daughter of the Dawn is a capably directed artifact featuring a priceless visual examination of its subject.

Film Review: ★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆