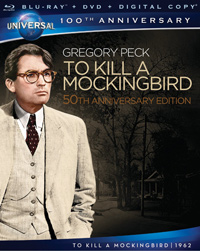

Universal Studios grants the all star treatment for the 50th Anniversary of a fundamental classic with Robert Mulligan’s adaptation of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. After all this time, the film hasn’t lost any of its potency as a document of rampant racism in 1932 Depression era South. But as powerful and as important as the film is, time has reinforced that, although as sensitively and honestly as it was made, this is a white man filtered tale of racism. More than a document of 1932, it betrays instead the social climate that both allowed such a film to be made and also informs the supposed liberal aspect of the film of 1962 era America, a taint that Lee’s novel was more easily able to avoid. As it stands, the film is one of the most significant examples of historical horror in the American classic film canon.

Universal Studios grants the all star treatment for the 50th Anniversary of a fundamental classic with Robert Mulligan’s adaptation of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. After all this time, the film hasn’t lost any of its potency as a document of rampant racism in 1932 Depression era South. But as powerful and as important as the film is, time has reinforced that, although as sensitively and honestly as it was made, this is a white man filtered tale of racism. More than a document of 1932, it betrays instead the social climate that both allowed such a film to be made and also informs the supposed liberal aspect of the film of 1962 era America, a taint that Lee’s novel was more easily able to avoid. As it stands, the film is one of the most significant examples of historical horror in the American classic film canon.

The title classically etched with a children’s crayon, we’re introduced to our 6 year old protagonist Scout (aka Jean-Louise) Finch (Mary Badham). Scout, an unabashed tomboy, caterwauls around the dusty southern town of Maycomb with her older brother Jem (Phillip Alford). Living with their stoic father, lawyer Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck) they are looked after by their black maid, Calpurnia (Estelle Evans). They befriend a new boy in town, Dill (played by John Megna, and apparently based on Truman Capote) who is sent to Maycomb during the summer to live with his aunt. The three youngsters share an obsessive fascination with the Radley house, their strange neighbors down the street. There’s legendary town gossip about the family, in particular, the Radley boy, coined Boo. Apparently, Boo only comes out at night, talked of between the children with gruesome, monsterish detail. Most of their antics revolve around trying to sneak a peak at the illustrious pariah, until the small town is suddenly brought to its knees when an ignorant white girl, Mayella Ewell (Collin Wilcox) and her hateful father (James Anderson) accuse Tom Robinson (Brock Peters), a black man, of raping her. Tensions rise when Atticus decides to represent Tom Robinson in court, resulting in an intense and gripping courtroom scene, climaxing in Atticus’ amazing closing statement. It’s no surprise that, despite obvious evidence that Mayella tried to seduce Tom and was viciously beaten by her father for it, he is found guilty.

No matter how many times you’ve seen To Kill a Mockingbird, or how long it’s been, the reading of the verdict, followed by Peck’s transfixing scene (perhaps his best on-screen moment ever), still manages to elicit a gasp, a visceral gut reaction. Peck deservedly won an Oscar for his role, but there are a few questionable moments concerning how black folks are portrayed that corroborate the racism of 1962. After the reading of the verdict, the black audience stands in the balcony, supposedly out of respect for Atticus. They wait for him to leave the courtroom before they disperse, out of respect for this great man. What about Tom Robinson? There was no type of reaction at all for him. Same goes for a scene right after, where we’ve discovered Tom’s been “accidentally” killed trying to escape (there’s an eye-roller for you) and Mr. Ewell calls on the Robinson household to find Atticus, demanding “Hey boy, fetch Atticus” to one of the men outside. There’s not even a beat skipped. No one reacts, out of fear we assume, for this small, toothless, straw hat wearing ignoramus. But then, that’s perhaps the point of the film. There’s a dense hopelessness about it, a specter that can’t be admonished even by the film’s “goes around what comes around” ending. Also, isn’t it strange that we never get to hear Mrs. Robinson speak? While our perspective is mainly from the children’s point of view, (besides Tom Robinson and Calpurnia, the black characters remain largely outside the frame), there’s an obvious discomfort with how the film handles the treatment of its black characters. In its defense, Fritz Lang made a film called Fury in 1936, the same decade this tale is set, in which he had to use a white man (Spencer Tracy) as a stand in for all the nameless and faceless black victims of lynch mobs. Twenty years later at least we could be a little more truthful.

Certainly, this is director Robert Mulligan’s most prolific title and his greatest achievement. Produced by Alan Pakula, the film also won Best Screenplay for Horton Foote, Best Art Direction, and nominations for Badham and Elmer Bernstein’s exceptional score. Much has been said about the wonderful performances of the children, but they’re the weakest part of the film. The narrative is told from the viewpoint of one, sometimes both of the children, but there’s a considerable distance we have from them. While Badham was Oscar nominated, her performance remains static throughout, the inner workings of her childhood thoughts and views of the world rarely surfacing.

The killing of the mockingbird refers to that spectral character of Boo Radley, who is personified by Robert DuVall in his onscreen debut, popping up to save Jem and Scout from the drunkenly murderous Mr. Ewell, who attempts to kill them in the woods late one night after a Halloween pageant. The sheriff deems that the publicity Boo would receive for accidentally killing Mr. Ewell would be too detrimental—after, all, why kill a mockingbird, a creature that exists only to give us joy with its musical talents? But after the poetry of this rationale falls away, you’re bound to come back to that haunting conclusion for Tom Robinson, who never had and never will have any justice, an unfortunate soul from those olden days, the victim of a horror that’s more palpably terrifying than any genre effort.

Disc Review:

The cultural influence of Harper Lee’s film and Robert Mulligan’s subsequent adaptation is undeniable. An enduring classic in many respects, it is just as much a dour reminder of the 1930’s as it is of filmmaking in the 1960’s. In all respects, it’s a brave piece of filmmaking. Arguably hindered by its white vantage point, it’s strangely more truthful than period pieces churned out depicting the time period in which it was filmed, such as 2011’s The Help (now there’s some serious whitewashing for you). Universal’s excellent Blu-ray transfer is presented in 1:85:1 and offers a DTS-HD Master audio 5.1 surround mix as well as the standard DTS 2.0 mix. As mentioned in the restoration feature, the process involved a series of ‘optical pushing’ in certain sequences, which becomes especially obvious in the courtroom scene involving the breakdown of Mayella Ewell. Overall, it’s a good transfer and the black and white cinematography is quite pristine throughout most of the film. While the extras pander to the altar of Gregory Peck as if he were the Olympian god that made the whole film possible, this 50th Year Anniversary edition is certainly a beautiful package.

Fearful Symmetry

Taking its title from William Blake’s poem, this feature length documentary by Charles Kiselyn concerns the making of To Kill a Mockingbird, featuring extensive interviews with Peck and other cast members. An informative feature.

A Conversation with Gregory Peck

This feature length documentary explores the life and career of Gregory Peck, with plenty of archive footage, interviews, film clips, intimate moments with family members, etc. An obvious treat for Gregory Peck fans, but it negates the necessity of the additional Peck extra features. For instance, there’s almost nothing about Robert Mulligan, except where he is mentioned as necessary in relation to Peck.

Academy Award Best Actor Acceptance Speech

Brief footage of Peck’s acceptance speech, presented to him by Sophia Loren is included. A rather humble and unremarkable speech, Peck thanks all the supporters of his work.

American Film Institute Lifetime Achievement Award

This is another acceptance speech from Peck in 1989 (from AFI, which he helped found in 1967), much later in his career and of considerably greater length. Peck mentions the decline of cinema, preaches that films shouldn’t only aspire to make money, quoting T.S. Eliot. Peck also thanks his wife and family and many of his leading ladies, many who were in the audience, including Jane Fonda, Dorothy McGuire, with a special thanks to Audrey Hepburn.

Excerpt From the Academy Tribute to Gregory Peck

Peck’s daughter introduces her four brothers and speaks about Peck as a father and how similar he was to Atticus Finch in real life. Again, interesting for the Peck aficionado, but feels a bit like Peck overdrive.

Scout Remembers

A 1999 interview with Mary Badham, cast as Scout as a young child, talks about her audition process and the close relationship that developed between her and Peck. Badham, who would only star in three more feature films in her lifetime, is constantly interrupted by film clips throughout the interview, until, appropriately, we are treated to what some of her favorite scenes with Peck were. A notable extra on a disc glorifying the film’s Oscar winning star.

Feature Commentary

Commentary from Robert Mulligan and producer Alan Pakula is available.

Theatrical Trailer

The film’s original theatrical trailer is included, which has Peck narrating as a selling point.

100 Years of Universal: Restoring the Classics

One of the most informative extras on the disc is this short feature which explains Universal’s restoration process of To Kill a Mockingbird and several other titles (though not everything will be restored—titles are selected by senior executives and film historians).

Final Thoughts:

The team at Universal has done wonders with this title and several others. The original grain of the film seems to be the problem when the images are magnified, so the restoration process includes optical pushing, which zooms in on the image. While at times this is easy to spot in Mockingbird, rather then remove the grain completely, a special process that ‘averages’ the grain across the image both before and after the optical push. Noticeable, perhaps, but the images are not only retained, but magnified and cleaned up.