This week’s edition of Tuesday Blus includes the following titles: Moses and Aaron (1975) – Grasshopper, For Love of Ivy (1968) – Kino, The Garden of Allah (1938) – Kino, plus DVD review of Happy Hour (2015) – Icarus.

Moses and Aaron (1975)

Film Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Grasshopper Film makes good on its release of the back catalogue from famed directing duo Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet with a Blu-ray transfer of their celebrated 1975 title Moses and Aaron, a filmed adaptation of the unfinished Schoenberg opera which premiered out of competition at the Cannes Film Festival and has been largely unavailable until now. Set entirely within the confines of an Italian amphitheater, the story of the Exodus unfolds in three parts. Schoenberg’s ominously offbeat music assists the celebrated long takes of Straub and Huillet, which together make an idiosyncratic experience (not unlike Bruno Dumont’s recent Jeannette, the Childhood of Joan of Arc which plays with certain cinematic and musical sensibilities).

Grasshopper Film makes good on its release of the back catalogue from famed directing duo Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet with a Blu-ray transfer of their celebrated 1975 title Moses and Aaron, a filmed adaptation of the unfinished Schoenberg opera which premiered out of competition at the Cannes Film Festival and has been largely unavailable until now. Set entirely within the confines of an Italian amphitheater, the story of the Exodus unfolds in three parts. Schoenberg’s ominously offbeat music assists the celebrated long takes of Straub and Huillet, which together make an idiosyncratic experience (not unlike Bruno Dumont’s recent Jeannette, the Childhood of Joan of Arc which plays with certain cinematic and musical sensibilities).

Moses (Gunter Reich) sing-talk battles with his brother Aaron (Louis Devos) for the ear of the downtrodden Jewish people, who argue over the capabilities of God vs. the pagan deities the latter brother professes to worship. The famed staff turning into a snake and the eventual Golden Calf make their grand entrances in this foreboding musical which takes the Biblical fable into the more Greek tragedy territory than a religious experience.

Compelling and formidable, Straub and Huillet turn Schoenberg’s opera into a fascinating cinematic experience which charts the regression of an oppressed people faced with deciding between hedonism or righteousness after experiencing a sense of hope and freedom.

Grasshopper presents Moses and Aaron as a new digital restoration which attempts to convey the title’s significant technical feats. Also, the package includes three short films from Straub and Huillet, including Machorka-Muff (1962), Not Reconciled (1964), and Introduction to Arnold Schoenberg’s Accompaniment to a Cinematographic Scene (1972).

***

Happy Hour (2015)

Film Review: ★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Unless one was lucky enough to catch it on its festival circuit tour after a celebrated premiere in competition at the 2015 Locarno Film Festival, or at its US showcase at MoMA in August of 2016, then Happy Hour, the latest feature from Ryusuke Hamaguchi, was unfortunately out of reach for most cineastes. The five-hour plus odyssey concerning four women and their ultimate relationship woes in contemporary Japan has all the sincerity and authenticity of an actual Girls Trip (although any real comparison between this and Hollywood spectacle should end here), and nabbed Best Actress awards out of Locarno for each of its four leads, all making exceptional debuts.

Unless one was lucky enough to catch it on its festival circuit tour after a celebrated premiere in competition at the 2015 Locarno Film Festival, or at its US showcase at MoMA in August of 2016, then Happy Hour, the latest feature from Ryusuke Hamaguchi, was unfortunately out of reach for most cineastes. The five-hour plus odyssey concerning four women and their ultimate relationship woes in contemporary Japan has all the sincerity and authenticity of an actual Girls Trip (although any real comparison between this and Hollywood spectacle should end here), and nabbed Best Actress awards out of Locarno for each of its four leads, all making exceptional debuts.

Beginning on somewhat of a Koreeda-ish note before it snakes into something like an Ozu inspired miniseries for its leading quartet of women, all in their mid-30s, begins at the end of another annual vacation they take together. We don’t get much of a sense of them beyond their mildly polite exchanges, all of which reveal three of them to be currently married while Akari (Sachie Tanaka), a no-nonsense nurse with a penchant for bluntness, is the only divorced member of the group. Slowly and painstakingly, we piece together their relationships, which was established at the behest of Jun (Rira Kawamura), who brought all the women together to form their current formation. Jun is closest with Sakurako (Hazuki Kikuchi), who she has known since high-school, and was the meddler responsible for her friend’s marriage with her reserved husband. But as Jun attempts to obtain a divorce from her own husband, who refuses to grant her wish, leading to a drawn-out court battle, the women each face their own relationship dilemmas, including fourth member Fumi (Maiko Mihara), who at last realizes she isn’t getting what she needs out of her own marriage. When Jun suddenly disappears, the remaining three set out to find her even as they question their own possibilities.

With Happy Hour, Hamaguchi weaves a compelling portrait of daily lives upset by existential dilemmas—are each of the women living up to their own potential? When Jun and her significant ennui disappear Antonioni style from the proceedings, the rest of them are forced to contend with the concept of absence—particularly of their group’s nucleus. Hamaguchi allows for several extensive sequences to play out across the five-hour running time, many of which are enriching and sometimes devastating conversations in which epiphanies occur, self-realizations are granted, and the strength and nature of friendship is tested. With great warmth and poignancy, Hamaguchi’s Happy Hour is perhaps one of the most satisfyingly nuanced portraits of the profundity lurking beneath the day-to-day grind.

Icarus releases Happy Hour on DVD only in this 2-disc transfer in 1.85:1. Picture and sound quality allows for proper submersion, but a Blu-ray offering would have been ideal (especially considering no extra features are included).

***

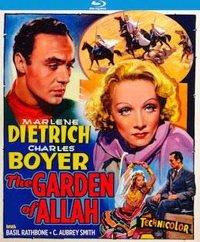

The Garden of Allah (1938)

Film Review: ★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

An antiquated melodrama from the 1930s, the star-crossed romance between Marlene Dietrich and Charles Boyer in The Garden of Allah, seems like an item which would be better known. Based on a 1904 novel by Robert Hichens (a famed British author perhaps better known for The Paradine Case, which Hitchcock adapted in 1947), this was Dietrich’s first motion picture in Technicolor and snagged two Oscar nominations (albeit for Best Assistant Director and a nod for Max Steiner’s score, which could be called ‘sweeping’) and was the third mounting of the material (silent versions were made in 1917 and 1927). Arriving just as Dietrich’s relationship with Josef Von Sternberg had ended (their last collaboration arrived the year prior, 1935’s The Devil is a Woman), this was perhaps the most anticipated venture for the 1930s icon that year (she would also headline films for Frank Bozarge and Henry Hathaway, the latter of which has fallen into obscurity) as producer David O. Selznick famously bought off actress Merle Oberon, who had been promised the role, so Dietrich could step in.

Dietrich stars as the convent raised Domini Enfilden, a woman who spent her entire adult life caring for her ailing father. When he passes, she seeks spiritual solace from the sisters who urge her to leave the city so she may find herself in the desert, a breeding ground for self-reflection and the locale which suggests the film’s title. Rather than learning to define her identity, Domini falls head over heels in love with a Russian traveler, Boris Androvsky (played by the French actor Charles Boyer), who just so happens to be a Trappist monk who only recently fled his temple after breaking his vows and losing his faith. United over a skirmish involving an exotic dancer (actress Tilly Losch, making her first screen appearance and who would only star in a handful of Hollywood films), they become traveling partners and eventually husband and wife. When forced to engage with ANY kind of religious conversations or figures, Androvsky behaves like a vampire in sunlight, and his secret is eventually uncovered by Basil Rathbone’s Count Ferdinand Anteoni. The incredibly pious Domini is shocked that a holy man would dare to break his vows for any kind of worldly reasons, and their third act dramatic conflict revolves around Androvsky ‘doing the right thing.’

While Dietrich had heretofore starred as boundary pushing vixen for Von Sternberg, this attempt to buttonhole her wiles simply doesn’t work (her eyebrows, for instance, always seem to tell a different story than whatever’s being relayed onscreen). It is, perhaps, her most unbelievable performance in a prolific career which spanned from the 1920s to the early 1960s. Polish émigré Richard Boleslawski seems more intent on establishing the lush ambience of the setting rather than coaxing any real feeling between his leads. A noted supporting cast includes Joseph Schildkraut (who would win a Best Supporting Actor Oscar two years later for The Life of Emile Zola) as a comical tour guide and John Carradine (who is obviously not the correct racial make-up) as a mystical sand diviner.

Kino Lorber presents the film in 1.33:1 in this transfer, which looks as if some portions of the print could benefit from a restoration (the film’s cinematography, which received an Honorary Award for Harold Rossen and W. Howard Greene, both uncredited, is its strongest asset). No extra features are included in the packaging.

***

For Love of Ivy (1968)

Film Review: ★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

One of the most prominent actor’s directors of the 1950s, director Daniel Mann (not be confused with Delbert Mann, director of Marty) was an early prominent figure out of the Actors Studio, whose influences can be credited for the rise of James Dean. Directing Shirley Booth to an Oscar in his 1952 debut Come Back, Little Sheba (which he had also directed on stage), the decade was incredibly notable for Mann, who also brought Anna Magnani and Elizabeth Taylor to Academy Awards glory for The Rose Tattoo (1955) and Butterfield 8 (1960)—and the former competed at the Oscars against Susan Hayward for I’ll Cry Tomorrow, which Mann also directed. By the 1960s, Mann’s influence began to wane with the changing tide of Hollywood, and his prominent item of note in the decade is the spy spoof Our Man Flint (1966). Before sliding into genre by the 1970s (he directed the first version of Willard in 1971), Mann helmed the Sidney Poitier vehicle For Love of Ivy, which perhaps seemed progressive during the period but now is most notable for how antiquated its racial politics are, despite being based on an original story from Poitier.

Abbey Lincoln stars as Ivy, a young housekeeper for an affluent white family. After announcing her wish to take leave of the Austin’s, grown children Gena (Lauri Peters) and Tim (Beau Bridges) panic, devising a plot to set Ivy up with a beau so she’ll stay on rather than pursuing a secretarial degree in New York City. Approaching Jack Parks (Sidney Poitier) into taking Ivy on a date after convincing the man, who works as an executive for their father’s (Carroll O’Connor) trucking company, it will be a wise career movie, the two eventually hit it off despite their differing levels of sophistication. However, Ivy soon learns of the scheme while Jack faces heat for an illegal night-time operation he oversees using the company’s trucks.

Featuring a soundtrack from Quincy Jones (who was nominated for an Oscar here), and a supporting cast which includes “All in the Family” star Carroll O’Connor (in a minor role) and a young Beau Bridges (Golden Globe nominated) as a privileged, meddling twentysomething, perhaps the best reason to revisit Ivy is for a chance to see famed jazz vocalist Abbey Lincoln in a Golden Globe nominated performance (though a better, grittier film is 1964’s Nothing But a Man) as the sympathetic title character, a maid for a white family attempting to better herself by leaving the comforts (and complacency) of their home. While the film does try to give us a side of Poitier we don’t see (especially as this came a year after his iconic role as the squeaky-clean genius academic in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?) since he runs an illegal gambling racket at night in the backs of elaborate big-rigs, the actor’s presence tends to negate any semblance of actual wrong-doing. What’s most irritating is having to watch two first-rate performers waddle around in the prose of this white perspective—after all, their ‘one-of-a-kind’ romance, as it’s described, is at the behest of the progressive whites they’re ‘lucky’ enough to be working for—and their romance is meant as a tool to keep Ivy in her place in the white family’s kitchen. Of course, the assumption of the children, that they just need to find a certain ‘kind’ of black man to romance their maid, is nothing new from the viewpoint of the heteronormative majority (the tactic continued to be used in celebrated film narratives decades later, as the same kind of demeaning set-up accompanies the Alfre Woodard/Danny Glover narrative of Lawrence Kasdan’s 1991 film Grand Canyon).

Kino Lorber presents For Love of Ivy in 1.85:1. Picture and sound quality are serviceable in this Blu-ray update of Daniel Mann’s title. No extra features are included in the packaging.

***