Point of No Return: A Curtiz Classic Resurrected

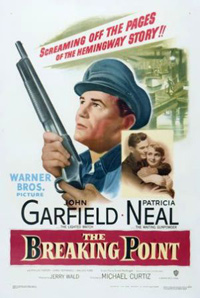

While history prizes a 1944 adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s story To Have and Have Not, there does exist a little seen (and more faithful to its source text) 1950 film version of the same story, helmed by Michael Curtiz, titled The Breaking Point. In retrospect, the earlier Howard Hawks version is all glitz and glamor and no guts, its claim to everlasting fame the guttural growl from Lauren Bacall concerning how to put your lips together to do something. Due to the insistence of screenwriter Ranald MacDougall (who wrote the screenplay for Curtiz’s Mildred Pierce and would later direct Ms. Crawford himself for his own debut in Queen Bee), the studio agreed to go forward with another adaptation, though got cold feet upon release due to star John Garfield being named in McCarthy’s witch hunt, and the film, unmarketed and unappreciated, came and went. Thankfully, this excellent film has been salvaged, and preserved with funding from Warner Bros. and the Film Foundation, and though it may not be ever own the reputation it deserves, it stands as one of the best Hemingway adaptations on the silver screen, and a damn fine film noir to boot.

While history prizes a 1944 adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s story To Have and Have Not, there does exist a little seen (and more faithful to its source text) 1950 film version of the same story, helmed by Michael Curtiz, titled The Breaking Point. In retrospect, the earlier Howard Hawks version is all glitz and glamor and no guts, its claim to everlasting fame the guttural growl from Lauren Bacall concerning how to put your lips together to do something. Due to the insistence of screenwriter Ranald MacDougall (who wrote the screenplay for Curtiz’s Mildred Pierce and would later direct Ms. Crawford himself for his own debut in Queen Bee), the studio agreed to go forward with another adaptation, though got cold feet upon release due to star John Garfield being named in McCarthy’s witch hunt, and the film, unmarketed and unappreciated, came and went. Thankfully, this excellent film has been salvaged, and preserved with funding from Warner Bros. and the Film Foundation, and though it may not be ever own the reputation it deserves, it stands as one of the best Hemingway adaptations on the silver screen, and a damn fine film noir to boot.

Harry Morgan (John Garfield) owns a charter boat, though he’s had considerable financial difficulties trying to keep both the boat and his dreams for it alive, trying to support his patient wife, Lucy (Phyllis Thaxter) and their two daughters, while also paying his employee and friend, Wesley (Juano Hernandez). Agreeing to transport a rich passenger (Ralph Dumke) while on a fishing trip taking them from Los Angeles to Mexico, he gets stiffed. He’s also saddled with the good-time dame his passenger brought along, the sassy and sexy Leona (Patricia Neal), and is forced to take a greasy lawyer, F.R. Duncan (Wallace Ford), up on an illegal deal transporting eight Chinese men to California just so he can afford to pull out of port. However, things go horribly wrong, and Morgan has to kill a man in self defense and skedaddle back to Los Angeles. However, as soon as he gets there, the coast guard is waiting to confiscate his boat, having been alerted by Mexican authorities. Meanwhile, his wife Lucy, having heard the rumors of a beautiful blonde on her hubby’s boat, gets agitated that Morgan’s eyes may be drifting. Between his financial trappings, his worried wife, a sexy temptress, and not to mention, blackmail and murder, Harry Morgan’s having a helluva time. With only Wesley as his friend and comrade, Harry Morgan is forced to take another deal from Duncan, or face losing his family.

While it may be arguable about Hawks or Curtiz being the more important auteur, it’s clear that Curtiz trumps his colleague with this effort. Whereas To Have and Have Not is consumed by the weight placed on Bogart and Bacall (and thus, is best remembered for their first, though it’s not their best, pairing) The Breaking Point is about a stubborn man, always doing things the hard way and thus, collapsing when he can’t carry the weight of the load. The three leads are all superbly effective, all thanks to a snappy, smart screenplay from MacDougall. You’d be hard pressed to find Garfield in better form. As for Patricia Neal, it’s hard to remember that she was an absolutely beautiful woman in the 1950s, and she’s got a look to match that scintillating voice in this picture—a woman of easy virtue never looked more damned sophisticated than Neal in her blonde bob. In one bar scene, Curtiz closes in on her wide open face, a large, white flower bursting open on her left shoulder, both beauties in full blossom. And while Phyllis Thaxter is in the less glamorous role as the mousy housewife, she’s absorbing and captivating as well. Early on in the film, she trembles feverishly, telling her rugged husband how “excited” she gets every time she thinks of him—-a hausfrau who still gets hot and bothered after two rambunctious kids, unpaid bills, and never ending housework. There’s just the right amount of chemistry, circumstance and subtlety on Thaxter’s part to make her just as memorable as the femme fatale. But her real chance to shine is when she gets to spar with Neal over the drunken Garfield, who can’t understand the hidden intent behind what they’re saying.

But above all this, The Breaking Point sports a closing shot that defines the racist, American hypocrisy of the 1950’s (though, one could argue that not much has changed), a final moment that was perhaps too subtle for audiences of the time period. You’ll have to watch The Breaking Point to catch it, but it does have something to do with non-white actor Juano Hernandez, whom the studio did not want to cast, but did so based on the absolute insistence of John Garfield. Because of this, Michael Curtiz was able to give us a brilliant final moment in one of his most unappreciated films.

Reviewed on June 23 at the 2012 Los Angeles Film Festival – Film Foundation Screening Program.

97 Min