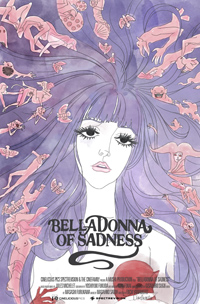

The Devil Inside: Yamamoto’s Cult Classic Restored to Gloriously Problematic Perversity

Cinelicious resurrects one of the most disturbing, sleazy and undeniably artistic animation endeavors ever made, Belladonna of Sadness, graced with a stupendous 4K restoration from an original 35mm negative. Made in 1973 by Eiichi Yamamoto, it was the final release from heralded Japanese anime studio Mushi Production (famed for a variety of successful anime series, such as “Astro Boy”), meant to be the third part of their Animerama trilogy of erotic animation efforts (following 1001 Nights the first X rated animation film ever, Cleopatra). Adapted from an 1862 feminist source novel from Jules Michelet, La Sorciere (aka Satanism and Witchcraft), which detailed the history of witchcraft as a rebellion against the church and feudalism, (meant to provide women and peasants with a sense of agency), Yamamoto crafts something much more insidious and offbeat with this striking feature, an odd juxtaposition of feminist empathies and (perhaps) the unintentional yet inherent misogyny in this rendering, calibrated specifically for the dual titillation and repulsion of the male gaze.

Cinelicious resurrects one of the most disturbing, sleazy and undeniably artistic animation endeavors ever made, Belladonna of Sadness, graced with a stupendous 4K restoration from an original 35mm negative. Made in 1973 by Eiichi Yamamoto, it was the final release from heralded Japanese anime studio Mushi Production (famed for a variety of successful anime series, such as “Astro Boy”), meant to be the third part of their Animerama trilogy of erotic animation efforts (following 1001 Nights the first X rated animation film ever, Cleopatra). Adapted from an 1862 feminist source novel from Jules Michelet, La Sorciere (aka Satanism and Witchcraft), which detailed the history of witchcraft as a rebellion against the church and feudalism, (meant to provide women and peasants with a sense of agency), Yamamoto crafts something much more insidious and offbeat with this striking feature, an odd juxtaposition of feminist empathies and (perhaps) the unintentional yet inherent misogyny in this rendering, calibrated specifically for the dual titillation and repulsion of the male gaze.

Opening with the film’s only moment of joy, a cheerful ditty announces the eternal bliss of Jean and Jeanne (Aiko Nagayama and Katsuyuki Ito), a peasant couple about to be married. However, they’re unable to afford the customary marriage tax which must be paid to the local baron (Masaya Takahashi). The baron’s cruel wife, jealous of the peasant woman’s incredible beauty, suggests the baron not only engage his prima nocta rights and claim her chastity, but allow all the other villagers access to her before she may return to her husband. Nearly ruining their marriage before it’s begun, the desolate Jeanne follows in Faust’s footsteps, engaging Satan in a bargain after the cheerful evildoer appears to her in the shape of a small phallus-like being, confirming through her will, he will grow. Exchanging earthly pleasures for survival techniques and magical powers to heal, Jeanne grows to be a feared pariah of the community until the Black Death ravages the land and her secrets involving the poison from the Belladonna flower allows her to save many people. Her reputation alarms the baron’s wife once more, who calls for the bewitched peasant woman to be scourged beneath the bowels of the castle until her flesh relinquishes the devil.

No description of what transpires on screen within the frames of Belladonna of Sadness can quite do it justice, but suffice it to say those with tastes for the extremely offbeat should relish this daring, eventually hysterical odyssey. Sexually perverse but not nearly as tawdry or gratuitous as described, Yamamoto skirts around the problematic exploitation of the female body by maintaining the perturbing, alarming core of woman as a controlled object, her desirability a double edged sword which allows her little agency. And though Satan crawls in and out of the frame, he’s never on hand as a preemptive fixture, instead gleefully sidling into her bed so she may be allowed to volley slight recourse. Countless approximations of vaginal imagery also abound, but there’s nothing innately sexy about what’s happening on screen, instead presenting sexual congress as a means of necessary yet unbalanced exchange for woman, with the ultimate prize represented as Satan breaking down Jeanne so she offers herself as his wife but of her own free will.

And although Belladonna of Sadness surpasses its own confounding limits by mutating in a rather endless (arguably tedious) montage of psychedelic, orgiastic mash-ups (including a complete break in tone where the film warps into an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink spasm), it contains an endless array of striking, unforgettable imagery. Jeanne’s rape sequence is more distressing than most live-action attempts of such a devastating act, her pale white body torn asunder by the pulsing, blood-red screen, the pool shattering into a clot of bats. Likewise, the penis-shaped devil is another introduction to behold in awe as a creepy, weird, and a significant visual metaphor.

Although the film’s bold, lascivious worship of Jeanne’s body equates to the same desecration enacted upon her as the actions of the cruel royals (the cartoon baron slightly resembles a perpetually sour Bill Nighy) and fickle villagers, it cannot be championed as the feminist promulgation Yamamoto hints at. However, it’s an audacious artifact from a fallen studio, hailing from a vintage era of antiquated acceptable representations—but it’s also one of the most resplendent and sublime theatrical releases, restoration or otherwise, you might see this year.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆