Come and See: Loznitsa Crafts Overwhelming Nightmare of Modern War-torn Ukraine

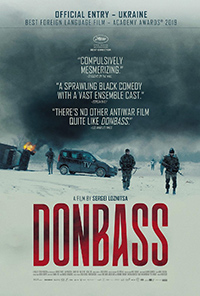

Dropping us directly into the wartime propaganda machine of modern-day eastern Ukraine, which has been torn asunder by the local government and pro-Russian separatists, Sergei Loznitsa delivers what’s simultaneously his most accessible and most brutal offering to date with the elliptical, vignette-styled Donbass. In many ways, this post-Orwellian exercise is most reminiscent of Loznitsa’s narrative debut My Joy (2010) in its violent deliberation of multiple characters consumed by a politically unsound landscape which has yielded a constant state of terror, paranoia, and incessant agitprop. Like the cinematic output of many of Loznitsa’s Soviet predecessors, there’s an overwhelming sense of being lost in translation for outsiders as pertains to certain cultural signifiers—and yet, despite the Kafkaesque sinkhole that is his latest, it’s a completely clear-eyed composite of hellish desperation and the contemporary detriments of systemic and unyielding propaganda.

Dropping us directly into the wartime propaganda machine of modern-day eastern Ukraine, which has been torn asunder by the local government and pro-Russian separatists, Sergei Loznitsa delivers what’s simultaneously his most accessible and most brutal offering to date with the elliptical, vignette-styled Donbass. In many ways, this post-Orwellian exercise is most reminiscent of Loznitsa’s narrative debut My Joy (2010) in its violent deliberation of multiple characters consumed by a politically unsound landscape which has yielded a constant state of terror, paranoia, and incessant agitprop. Like the cinematic output of many of Loznitsa’s Soviet predecessors, there’s an overwhelming sense of being lost in translation for outsiders as pertains to certain cultural signifiers—and yet, despite the Kafkaesque sinkhole that is his latest, it’s a completely clear-eyed composite of hellish desperation and the contemporary detriments of systemic and unyielding propaganda.

In the Donbass region of Eastern Ukraine, which borders Russia, a conflict raging since 2014 has left the area in extreme disorder. Various criminal gangs, who spar with local Russian troops and the Ukrainian regular army have created a world gone haywire. The civilian population has degraded significantly, and as someone somewhere once said, chaos reigns. We follow various sections of Donbass afflicted by this new world order, beginning with a band of locals being prepped to stage the aftermath of a fake attack for the ‘news.’ The sound of a bomb compels them to halt—but whether or not this is part of their scenario is unclear. Next, an outraged civilian dumps excrement on an official leading a government assembly, followed by a vitriolic standoff. Later, a woman of means attempts to drag her mother from the underground bomb shelter she inhabits with a bunch of other hapless people. Men are yanked off a bus and forced to undress, castigated by Russian troops for not defending the motherland on the frontline. Worse off is a Ukrainian army captive who is tied to a street pole and abused with vehemence by locals, some of whom question whether he’s an actor. Somehow, the comic insanity of an ensuing wedding makes the direct observations of violence even more discomfiting.

If the miserabilism of My Joy is an obvious point of comparison for Donbass, so is nearly every narrative and documentary feature of the director’s since then, of which he debuts one or the other on an annual basis. Reuniting with DP Oleg Mutu, Donbass is also similar, if more cohesive, than his esoteric reimagining of Dostoevsky’s A Gentle Creature, which formulated equally unnerving nightmares and dreamscapes (including a rape sequence even more horrifying for its visual implications). Beginning with the staging of a “fake news” item, it ends more or less where it begins, in an elliptical repetition of hellaciousness which gets worse with every revolution. A crescendo of meta-propaganda leaves us alone with closing credits which are merely a comfort for providing us with an escape, and a portrait of war-torn degradation as surely unforgettable as Elem Klimov’s war-horror standard Come and See (1985).

Difficult to digest and perhaps ultimately fodder for those die-hard art-house enthusiasts with a yen for masochism and misanthropy, Donbass is Loznitsa’s most masterful output to date—at the very least, in how it marries miserabilism with contemporary subtexts which once were envisioned as science-fiction and have now become a convoluted reality. In the staggering finale, it seems we are all merely doomed to reap what we sow, as the abused are fated to becomes the abuser and the world collapses in upon itself.

Reviewed on May 9th at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival. Un Certain Regard – Opening Night Film. 121 Mins.

★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆