Father Figure, Mother Tongue: Dulude-De Celles Curates Reconciliation

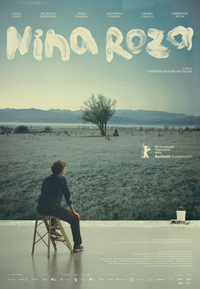

It turns out you can go home again…but don’t expect not to confront psychic wounds left untended, at least according to Nina Roza, the second narrative feature from Canadian filmmaker Geneviève Dulude-De Celles. The title refers to the names of two young girls who are of extreme significance to an art curator who immigrated to Montreal from Sofia, Bulgaria nearly thirty years ago. Professional circumstances allow for a coincidental reconciliation with his native country, but the results couldn’t be more personal. It’s a noiseless film, overtly a character study about one man’s journey towards discovering what actual role he’s playing in the curation of artists as well as examining the agency he may have denied his own child by neglecting her native heritage.

It turns out you can go home again…but don’t expect not to confront psychic wounds left untended, at least according to Nina Roza, the second narrative feature from Canadian filmmaker Geneviève Dulude-De Celles. The title refers to the names of two young girls who are of extreme significance to an art curator who immigrated to Montreal from Sofia, Bulgaria nearly thirty years ago. Professional circumstances allow for a coincidental reconciliation with his native country, but the results couldn’t be more personal. It’s a noiseless film, overtly a character study about one man’s journey towards discovering what actual role he’s playing in the curation of artists as well as examining the agency he may have denied his own child by neglecting her native heritage.

Nina Roza is a quiet film about interior emotional shifts, and utilizes subtlety, sometimes to its detriment. There are some striking similarities with another Montreal set Berlinale title, Memory Box (2021) from directors Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, where an immigrant family finally confronts forgotten memories from Beirut. Nina refers to Mihail’s (Galin Stoev) biological daughter, the first character we meeting in the opening credits, drifting away from a children’s birthday party and wishing to stay with her father for a few days, citing an unnamed existential ennui which has left her emotionally adrift in her marriage. Simultaneously, Mihail is made aware of a potential eight-year-old painting prodigy in a small Bulgarian village, who has just been signed by a notable Italian agent currently having trouble convincing the art world of her new client’s merits. Mihail’s colleague believes it’s a good opportunity to jump onboard while her art is still affordable, but someone needs to go meet the young girl and verify if she’s indeed a savant or being manipulated by her parents for publicity. Mihail îs originally from Bulgaria but seems to have significant trepidation about returning home, a place he fled when his wife died long ago. But once there, he meets Roza (Michelle Tzontchev), and after earning her trust, it appears she’s the real deal. But Roza has no interest in being uprooted in a planned transplant to Florence. Mihail must weigh if his involvement actually assists the child’s best interests.

While the Bulgarian countryside is certainly picturesque, there’s something surprisingly drab about DP Alexandre Nour Desjardins’ frames, especially considering it’s a film about art, both as a process and curation. And although Mihail’s correspondent with Roza does force him to reminisce about his daughter, Nina might as well be a ghost haunting the narrative for all we eventually learn about her (though adult Nina shows up just in time for one of dad’s speeches directly referencing her in the finale). Likewise what appears to be the real core of his trauma, involving his estranged sister, feels like the more central, meaty issue. The film treats this side character much like Mihail, an afterthought he addresses because he’s coincidentally in the area and also, finally, open to acknowledging his undefined absence. But this reconciliation is chummily administered, a mild spat cleared up over Bulgarian stew and cigarettes.

As Mihail, Galin Stoev is a stoic but inviting screen presence (and bears a striking resemblance to Italian actor Emilio Germano), but it’s unclear what exactly the resolution is. Yes, the journey is the destination in Nina Roza, but it’s a film that merely presents past and present situations regarding two young women who could potentially be assisted by mental health resources. Questions are posed, but potentially undesirable responses are not pondered.

Reviewed on February 16th at the 2026 Berlin International Film Festival (76th edition) – Main Competition. 103 mins.

★★½/☆☆☆☆☆