What Women Want: Feng’s Lusciously Filmed Satire a Wearying Critique on Cultural Custom

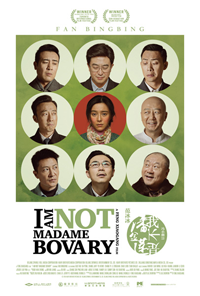

Prolific Chinese director Xiaogang Feng, whose films are often well-regarded box office hits back home, unveils his most internationally lauded effort to date with the impudently titled I Am Not Madame Bovary. A withering legal system satire obsessively detailing one woman’s struggle to achieve a sort-of vengeance while reclaiming her sullied reputation, writer Liu Zhenyun adapts from his own novel I Did Not Kill My Husband, which is perhaps a more fitting title for those presuming Flaubert’s tragic heroine casts a dark shadow here. In many ways, this literary toned melodrama plays like a more genteel version of Kafka, wherein a woman engages in endless battle with a slippery bureaucratic process designed specifically to elude her success. At times bleak and frustrating, Feng’s curious decision to frame the film almost entirely in a circular orb (as if we’re viewing her struggle through a telescope, with pronounced digressions) lends the film a fragile antiquity, often succeeding in a such wonderfully detailed spheroid frames he achieves a breathless bit of visual poetry. Paired with a complex performance from lead actress Bingbing Fan (who Westerners know as Blink from the X-Men franchise), an otherwise slight, arguably trite narrative makes this sharply observed beauty of a film all the more bitter and brittle.

Prolific Chinese director Xiaogang Feng, whose films are often well-regarded box office hits back home, unveils his most internationally lauded effort to date with the impudently titled I Am Not Madame Bovary. A withering legal system satire obsessively detailing one woman’s struggle to achieve a sort-of vengeance while reclaiming her sullied reputation, writer Liu Zhenyun adapts from his own novel I Did Not Kill My Husband, which is perhaps a more fitting title for those presuming Flaubert’s tragic heroine casts a dark shadow here. In many ways, this literary toned melodrama plays like a more genteel version of Kafka, wherein a woman engages in endless battle with a slippery bureaucratic process designed specifically to elude her success. At times bleak and frustrating, Feng’s curious decision to frame the film almost entirely in a circular orb (as if we’re viewing her struggle through a telescope, with pronounced digressions) lends the film a fragile antiquity, often succeeding in a such wonderfully detailed spheroid frames he achieves a breathless bit of visual poetry. Paired with a complex performance from lead actress Bingbing Fan (who Westerners know as Blink from the X-Men franchise), an otherwise slight, arguably trite narrative makes this sharply observed beauty of a film all the more bitter and brittle.

A narrator (Feng) gives us a brief overview of the history behind the legend of Pan Jinlian, a 17th Century adulteress whose name does not yield desirable connotation for those unlucky enough to be compared to her. But our modern narrative begins ten years in the past from contemporary climes, concerning the struggle of Li Xuelian (Bingbing Fan), who seeks the services of a judge she suggests is a distant relation to help her divorce the ex-husband she has already divorced. It turns out Lian’s ex-husband Qin Yuhe (Li Zonghan) hatched a plot with his wife to divorce her so they could secure a better apartment. But upon receiving the property, Qin Yuhe married another woman. For the next ten years, Lian struggles to navigate a murky justice system to regain her reputation and dignity with varying degrees of success thanks to a transitioning totalitarian governing body, with each significant player afforded his own set of motivations and angles.

Having won top prize at the 2016 San Sebastian Film Festival, I Am Not Madame Bovary should allow Feng more distinction abroad—he’s snagged plenty of awards throughout a career which began in 1994 with his debut feature Lost My Love, and picked up a special mention in Venice for 2006’s The Banquet (a glossy, bustling, action oriented adaptation of Hamlet). Feng provides intermittent narration himself, which, along with DP Luo Pan’s sumptuous and crisp frames, enhances Lian’s posturing as a tragic literary heroine. The framing morphs into a square aspect ratio when she makes two different journeys to Beijing, which isn’t explained, but signifies a segue from the bubble of Lian’s existence (her hopes, dreams, and desires to regain her dignity) with the guise of the real world, a brutal system of lines, divisions, and the semblance of justice. Madame Bovary (who is not mentioned in the Chinese title), is referenced via Feng’s narration, but the real specter haunting his film is Pan Jinlian, an infamous adulteress from Chinese folklore, and whose name is a shorthand colloquialism for a fallen woman, which Lian has been deemed following her sham divorce (in Western terms, think Jezebel).

What transpires plays like a delirious sister film to Ronit and Shlomi Elkabetz’s Gett: The Trial of Vivian Amsalem (2014), wherein a woman is forced to go to great lengths to secure a divorce. Considering the navigation of a complicated system of ownership, Feng’s title also is reminiscent of Luis Garcia Berlanga’s recently restored The Executioner (1963), an acute social satire about the lengths people are forced to retain property or obtain love under Fascist rule.

Although Fan’s Lian isn’t allowed a characterization beyond her struggle, Feng’s film allows for a gentle examination of how choices and actions directly affect others. In one of the film’s more poignant moments, the contemporary version of Lian has a chance encounter with an official who she succeeded in getting fired from his post for his ineptitude. To explain herself, she reveals the secret circumstances which led to her agreement with her husband, and we come to realize just how deeply she’s a woman scorned before Feng carries us away on a moment as matter-of-fact and brisk as an autumn gust of wind.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆