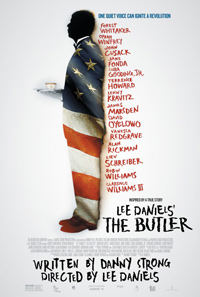

Once More With Feeling: Daniels’ Latest an Elegant, Necessary Recuperation

Previously berated by Armond White as helming the most racist film since The Birth of a Nation with his breakout 2009 hit, Precious, Lee Daniels’ shows his softer side with The Butler, a dizzying tunnel through several of America’s most tumultuous periods as seen through the eyes of a black butler working in the White House. White’s denouncement of Daniels is, in itself, indicative of the divisiveness inspired by unseemly or unwholesome portrayals of black characters in film, especially coming from a filmmaker like Daniels who has been operating outside of the cloying weight of a niche market. If the applause and accolades bestowed upon Precious were the result of (sub)conscious white guilt, the same guilt-ridden parties weren’t feeling quite as gracious for Daniels unfairly dismissed follow-up, 2012’s The Paperboy, a pulpy period piece that has brilliant flourishes of subversive elements that went largely unaddressed (what on earth do we do with the McConaughey character, a man who’s broken, busted visage presents us with a lurid metaphor of the cultural worth of a gay white man who sleeps with black men). A formidably cast epic that eclipses over seventy years of a man’s life in a landsape of evolving racism, Daniels lets his material speak for itself, while history calls the shots.

Previously berated by Armond White as helming the most racist film since The Birth of a Nation with his breakout 2009 hit, Precious, Lee Daniels’ shows his softer side with The Butler, a dizzying tunnel through several of America’s most tumultuous periods as seen through the eyes of a black butler working in the White House. White’s denouncement of Daniels is, in itself, indicative of the divisiveness inspired by unseemly or unwholesome portrayals of black characters in film, especially coming from a filmmaker like Daniels who has been operating outside of the cloying weight of a niche market. If the applause and accolades bestowed upon Precious were the result of (sub)conscious white guilt, the same guilt-ridden parties weren’t feeling quite as gracious for Daniels unfairly dismissed follow-up, 2012’s The Paperboy, a pulpy period piece that has brilliant flourishes of subversive elements that went largely unaddressed (what on earth do we do with the McConaughey character, a man who’s broken, busted visage presents us with a lurid metaphor of the cultural worth of a gay white man who sleeps with black men). A formidably cast epic that eclipses over seventy years of a man’s life in a landsape of evolving racism, Daniels lets his material speak for itself, while history calls the shots.

A fictionalized account based on Wil Haygood’s 2008 Washington Post article “A Butler Well Served by This Election,” which detailed the real life story of former White House butler Eugene Allen, Lee Daniel’s The Butler recounts these events through a character named Cecil Gaines (Forest Whitaker). Beginning in 1926, young Cecil resides on a cotton farm in Macon, Georgia. The vicious murder of his father at the hands of their employer, Thomas Westfall (Alex Pettyfer), causes Cecil’s mother Pearl (Mariah Carey) to unravel, while the Westfall matriarch (Vanessa Redgrave) trains Cecil as a house servant. As a young man, he sets off on his own, and a kindly father figure (Clarence Williams III) takes Cecil under his wing and trains him as a butler. Later receiving an offer to work at an elite hotel in Washington, D.C., Cecil relocates, and he leaves quite an impression on an administrator at the White House, where he is eventually offered a position.

Cecil is able to insure a comfortable middle-class existence for his wife Gloria (Oprah Winfrey) and sons Louis (David Oyelowo) and Charlie (Elijah Kelley), and makes lasting relationships with his fellow staff members Carter Wilson (Cuba Gooding Jr.) and James Holloway (Lenny Kravitz). But the changing cultural climate soon generates a rift between Cecil and his son Louis, who criticizes his father for being submissive, and soon takes off for school to join the Freedom Riders, and eventually the Black Panthers. While Gloria battles alcoholism and engages in an affair with Howard (Terrence Howard), the smarmy neighbor next door, Cecil is privy to the constant discussions happening within the Oval Office, his quiet and steadfast presence an imperatively visible figure to a host of presidents that would go on to make detrimental decisions pertaining to race relations in the US (not to mention, the long road to equal pay for black staff members at the White House). Just as unrest unspools in the country at large, so does the climate at the Gaines’ home.

Certainly, The Butler is the least sensational entry, thus far, in Daniels’ already illustrious filmography. The powerful story that unfolds, from a point of view that trumps historical familiarity, is allowed to tell itself, unfettered by an alarming amount of high profile cameos, and without the manipulative schmaltz of something like Forrest Gump. In fact, as its PG-13 rating indicates, Daniels doesn’t spend time reveling in exploitation, though there are a handful of emotionally traumatic sequences, including a vicious murder early on, and a volatile sit-in.

The Butler is hardly the sanitized gloss as depicted in The Help, and though he keeps a reserved distance from the despicable violence, moments of abject, racially charged hatred are bluntly unspooled. There are a lot of pretty faces in The Butler, but he doesn’t give the events a facelift. Instead, like Whitaker, we’re kept rather in the womb of the White House, privy to private snippets of conversations that precede momentous decisions and happenings. It’s a testament to Daniels and his bevy of showy stars that no one ever usurps the subtlety of Whitaker’s moving performance. A cavalcade of presidents, as portrayed by Robin Williams, James Marsden, Liev Schreiber, John Cusack, and Alan Rickman (and then, Jane Fonda as Nancy Reagan), are just blips on the radar. If anything, The Butler belongs to Whitaker and Oprah Winfrey, in her first role since 1998’s sorely underrated Beloved (and mention should be made of some resoundingly strong support from David Oyelowo). Winfrey’s performance as Gloria is candid and subtle. One of the most known figures in the world, she disappears imperceptibly into the role of a warm mother and unfulfilled housewife. This is, foremost, about one family’s struggles to reconcile despite the cultural forces that tear them apart. Daniels opens with a quote from Martin Luther King, Jr., “Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that,” which is the basic essence at hand here, as a father and son fight on opposing ends of the same struggle.

While based on the true story of real life butler Eugene Allen, we can assume certain liberties were taken in the construction of this fictionalized account, but that’s no matter. What should transcend political affiliations is a powerful finale, revisiting the results of the 2008 election with the added weight of the account we’ve just witnessed. In a year that’s bathed us in the aftermath of Trayvon Martin’s tragedy and the gross inappropriateness from the mouths of Paula Deen and Rae Dawn Chong, racism is not only and alive and well, but consciously cultivated and perpetuated in our culture.

While The Butler may be a mainstream effort from the delightfully offbeat Daniels (this is the project that he pursued after funding went unsecured for his MLK project Selma, now thrillingly in the hands of Ava DuVernay), one cannot overlook the importance of Gaines/Allen’s point of view and the global audience it has the capability of reaching. Daniels has crafted an elegant, artistic achievement that, more than anything, leaves us with the possibility of brighter things to come.