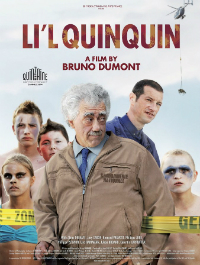

Life of Quinquin: Dumont’s Foray into Miniseries Format Filled with His Brand of Peculiar Humor

Provocative auteur Bruno Dumont lets loose his comedic side with a four part miniseries, Li’l Quinquin, shown as one long piece at the Cannes Film Festival. While it apparently will be released in English speaking territories in the same fashion, its purposeful structure does make it seem better served to be viewed in more than one sitting, where its bizarre weirdness has a better chance of really sinking in. But one has to remember that we’re talking about Dumont here, the director who grapples with existential ennui usually through the lens of religious discord or the bleak isolation of rural settings. So the project is indeed the most comedic offering of the director’s oeuvre, following last year’s captivating look at sculptor Camille Claudel starring Juliette Binoche. Yet it’s not standard comedy by any possible means. Filled with droll instances amongst its colorful cast of characters, strange murders and a bumbling police detective are the driving force behind yet another unique and compelling feature from Dumont.

Provocative auteur Bruno Dumont lets loose his comedic side with a four part miniseries, Li’l Quinquin, shown as one long piece at the Cannes Film Festival. While it apparently will be released in English speaking territories in the same fashion, its purposeful structure does make it seem better served to be viewed in more than one sitting, where its bizarre weirdness has a better chance of really sinking in. But one has to remember that we’re talking about Dumont here, the director who grapples with existential ennui usually through the lens of religious discord or the bleak isolation of rural settings. So the project is indeed the most comedic offering of the director’s oeuvre, following last year’s captivating look at sculptor Camille Claudel starring Juliette Binoche. Yet it’s not standard comedy by any possible means. Filled with droll instances amongst its colorful cast of characters, strange murders and a bumbling police detective are the driving force behind yet another unique and compelling feature from Dumont.

In a rural farming community in northern France, a young boy named Li’l Quinquin (Alan Delhaye), which actually means young kid, is the ringleader of a band of generally harmless young troublemakers. Short in stature and with a hearing aid, the rebellious young tyke loves lighting off firecrackers at inopportune moments while hanging out with buds and the apple of his eye, young Eve (Lucy Caron), who tends to carry her trumpet with her wherever she goes. When a dead cow is discovered in a bunker, the police discover that a human body has been stuffed inside the remains of the cow, though all seem unsure whether the remains were stuffed in the front or back end of the poor animal. Leading the investigation is Captain Van Der Weyden (Bernard Pruvost) and his partner, Carpentier (Philippe Jore). Weyden’s intense facial expressions and fidgety movements make him seem like he stepped right of a silent era comedy. In the next episode, a second body is discovered inside another cow, and a scenario begins to take place. The two corpses, both married, had been lovers. They suspect the husband of the dead female….only, he ends up being murdered, too.

If this sounds like familiar territory in the realm of Dumont, it’s because his 1999 sophomore film, Humanite, which won the Jury Prize at Cannes, concerns a peculiar police detective investigating the rape and murder of an 11 year old girl (Emmanuel Schotte took home a Best Actor prize, as well). Dumont mines a similar scenario for more comical effect and, to his credit, Li’l Quinquin feels even more impressive in this regard (which leads one to wonder, what would Twentynine Palms look like from a comedic angle)?

Bernard Pruvost’s hilarious performance as the rather strange and affected Van Der Weyden deserves considerable attention. He’s a complicated series of tics and slogans, an addlepated, impatient twit, stealing the spotlight from the eponymous child character Quinquin, an equally spirited personality. As we follow along with the investigation, a series of underlying issues in the community begin to surface, ranging from typical extramarital affair scenarios to more devious matters regarding race relations and ignorant views on immigration. And thus, the film also recalls Dumont’s 1997 debut, The Life of Jesus, about a group of unemployed young men that direct their anger toward Arab immigrants.

If you’re looking for a typical whodunit scenario, Bruno Dumont’s film is not the place to find it—nor would you want it to be. While Li’l Quinquin arguably works better if viewed in four separate pieces (to watch in one sitting does feel like a considerable undertaking), it’s another unique film from Dumont, whose knack for comedy is as delightfully off center as his more dramatic entries.

Reviewed on May 19th at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival – Directors’ Fortnight – 197 Minutes

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆