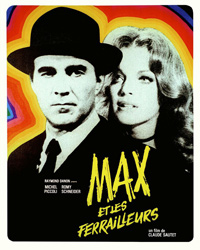

Crime and Punishment: Sautet’s Enthralling Policier an Obscure Neo-Noir

Following the international acclaim of his 1970 film The Things of Life, Claude Sautet re-teamed with his leads Michel Piccoli and Romy Schneider for a return to the criminal tendencies comprising his earlier filmography as a director. Less well known today than his 1960 classic Classe Tous Risques, Sautet’s 1971 devious psychological drama Max and the Junkmen is well worth reexamination in modern contexts. As has been pointed out before, Sautet’s genre efforts have long languished in the shadows of Jean-Pierre Meville’s filmography, with well-renowned crime sagas like Le Samourai (1967) and Le Cercle Rouge (1970) having already been released by the time Sautet hit his stride. But while Melville’s celebrated filmography focuses on precise elaboration, Sautet’s outings within genre tend to be character oriented, in particular lending this title a melancholy tint, doubled over in its final, dramatic climax.

Following the international acclaim of his 1970 film The Things of Life, Claude Sautet re-teamed with his leads Michel Piccoli and Romy Schneider for a return to the criminal tendencies comprising his earlier filmography as a director. Less well known today than his 1960 classic Classe Tous Risques, Sautet’s 1971 devious psychological drama Max and the Junkmen is well worth reexamination in modern contexts. As has been pointed out before, Sautet’s genre efforts have long languished in the shadows of Jean-Pierre Meville’s filmography, with well-renowned crime sagas like Le Samourai (1967) and Le Cercle Rouge (1970) having already been released by the time Sautet hit his stride. But while Melville’s celebrated filmography focuses on precise elaboration, Sautet’s outings within genre tend to be character oriented, in particular lending this title a melancholy tint, doubled over in its final, dramatic climax.

Former judge Max (Piccoli) is now a police inspector with a chip on his shoulder having seen too many criminals escape the clutches of justice thanks to a lack of hard evidence. A loner who came from a family of rich vintners, Max works for pleasure, and it’s his greatest desire to put criminals behind bars and perhaps gain the acclaim accompanying such feats. Fate deals him a chance to manipulate his destiny when he runs into Abel (Bernard Fresson), a mate of Max’s from decades ago. Abel doesn’t hold back explaining his current occupation, basically stealing scrap metal and random cars in order to gain money for the materials, while Max remains vague about what he does. After their chance encounter, Max visits the commissioner (Georges Wilson) and explains he has hard info on a group conspiring to commit a bank robbery—perhaps they can catch them red-handed and put them conveniently in prison. The commissioner takes the bait and contacts the inspector whose jurisdiction Abel and his gang are operating within, the fastidious Rosinsky (Francois Perier). Shocked at the news, Rosinsky insists Abel’s group is small time, and his informant, Dromedary (Henri-Jacques Huet) hasn’t divulged any such plans. Nevertheless, Max insists this is true, and uses Rosinsky to get information about Abel’s girlfriend, a beautiful German prostitute named Lily (Romy Schneider). Max approaches her as a client, posing as a bank manager, feeding her information she leaks to Abel and his crew, instigating them to commit the crime.

Max is clearly an appalling individual, and is brilliantly played by Piccoli as an increasingly agitated sort full of slight tics. His downfall happens to be the developing feelings he begins to have for the hesitant Lily, a very chic, arrestingly beautiful Schneider, so inviting we can believe she has the capability for chemistry with both the stiff Piccoli and the burly, kindhearted Fresson.

Max’s manipulations feel awfully similar to another recent despicable protagonist, the Jake Gyllenhaal character in 2014’s Nightcrawler, eschewing empathy for his fellow man in the pursuit for fame and glory of the socially sanctioned. DoP Rene Mathelin, known for his work on Yves Richards’ comedies, manages a perpetually overcast feel here, and Max and the Junkmen manages to be an emotionally potent mix of dangerous ideals and class struggles. The film didn’t see a theatrical release in the US until 2012, courtesy of Rialto Pictures, so its inclusion in this Sautet roadshow is an excellent opportunity to see a neglected French classic.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆