The Mind is Its Own Place: Konchalovsky Returns with a Grueling, Haunting Holocaust Triptych

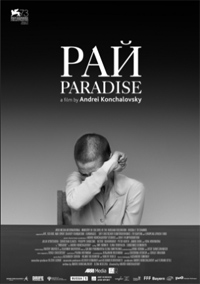

In all likelihood, there will never be an end to cinematic representations of the Holocaust, at least not as long as the moving image exists as a narrative platform. We’ll continue to have weepy melodramas, biopics, adventure films, and garishly mounted spectacles reenacting the visceral violence of the generation defining war. Villainous Nazis have been utilized metaphorically and allegorically, across all widespread types of honorable vehicles as well as exploitative, manipulative showboating. But few cut to the quick in the guise of anxiety-laced poetry as Russian director Andrei Konchalovsky’s latest film, the beautifully photographed Paradise, which premiered at the 2016 Venice Film Festival where he won Best Director (interestingly, alongside Francois Ozon’s Frantz, which utilizes a similar visual palette to examine tenuous relationships between a German woman and a French man following the war). Konchalovsky, an iconic figure from Russia’s cinematic landscape, who toiled as screenwriter for Tarkovsky before embarking on his own directorial career in the mid-1960s, which included a lengthy stay in Hollywood from the mid-1980s to early 1990s (yielding such output as Runaway Train and Tango & Cash), concocts something shockingly visceral with this German-Russian co-production. A curiously styled hybrid of docu-confessionals interspersed with a myriad of non-linear flashbacks to crank up a triptych inspired narrative about three intersecting people moving from Nazi occupied France to the hellish barracks of a squalid concentration camp, it can’t be described as a pleasant experience, but it’s certainly well-crafted and unforgettable.

In all likelihood, there will never be an end to cinematic representations of the Holocaust, at least not as long as the moving image exists as a narrative platform. We’ll continue to have weepy melodramas, biopics, adventure films, and garishly mounted spectacles reenacting the visceral violence of the generation defining war. Villainous Nazis have been utilized metaphorically and allegorically, across all widespread types of honorable vehicles as well as exploitative, manipulative showboating. But few cut to the quick in the guise of anxiety-laced poetry as Russian director Andrei Konchalovsky’s latest film, the beautifully photographed Paradise, which premiered at the 2016 Venice Film Festival where he won Best Director (interestingly, alongside Francois Ozon’s Frantz, which utilizes a similar visual palette to examine tenuous relationships between a German woman and a French man following the war). Konchalovsky, an iconic figure from Russia’s cinematic landscape, who toiled as screenwriter for Tarkovsky before embarking on his own directorial career in the mid-1960s, which included a lengthy stay in Hollywood from the mid-1980s to early 1990s (yielding such output as Runaway Train and Tango & Cash), concocts something shockingly visceral with this German-Russian co-production. A curiously styled hybrid of docu-confessionals interspersed with a myriad of non-linear flashbacks to crank up a triptych inspired narrative about three intersecting people moving from Nazi occupied France to the hellish barracks of a squalid concentration camp, it can’t be described as a pleasant experience, but it’s certainly well-crafted and unforgettable.

In 1942 France, Olga (Julia Vysotskaya), a Russian Countess working as a Vogue fashion editor, is arrested for harboring two Jewish children. Interrogated by French police officer Jules (Philippe Duquesne), a daffy yes man who tries to explain to his wife though they’re technically in collusion with the Gestapo, his role is not the same thing, Olga attempts to seduce him to gain leverage. Unfortunately, Jules meets a tragic end at the hands of the French Resistance, and Olga is transported to a concentration camp for her crimes. As luck would have it, she is chanced upon by SS Officer Helmut (Christian Clauss), a handsome and formidable Aryan idealist who has risen quickly through the ranks to become an Ubermensch, tasked with auditing the internal machinations of the camps (where there seems to be an awful lot of corruption going on). Years prior, Olga and Helmut had been lovers during a chance encounter in Italy, a moment he is eager to recreate. As Hitler’s foothold wanes, the reintroduced lovers try to formulate a plan of escape.

The cinematic legacy of the Holocaust is a daunting and unprecedented one, and there’s a certain perverse audacity involved in continually resurrecting it. Harrowing and unforgettable though it may be, 2015’s Son of Saul, for instance, like Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, aren’t items to be consumed casually, and such titles often warrant defense against those willing to dismiss these attempts as art-house torture porn. Konchalovsky easily ends up in the ballpark of fellow countryman Elem Klimov, whose 1985 title Come and See, is certainly one of the most formidable attempts to convey the ravages of WWII. Like Klimov, Konchalovsky dangles Biblical inspiration at us from the title. Whereas Come and See was a phrase lifted from Revelations, Paradise evokes both Hitler’s desire to create a German themed heaven-on-earth as well as Milton’s timeless poem Paradise Lost, a depiction of the fall of man into utter degradation.

Konchalovsky reunites with scribe Elena Kiseleva and DP Aleksandr Simonov (both of whom were involved with his 2014 title The Postman’s White Nights), to concoct a visually poetic, often stunningly elegant examination of suffering, sacrifice, and the dangerousness of zealous national and religious identity. In many way, the film’s particular style recalls the early Jean-Pierre Melville title Le Silence de la Mer (1949), where a sympathetic Conrad Vernon stars as a Nazi soldier in occupied France. Similar to Laszlo Nemes’ Son of Saul, the film was shot in the boxy Academy aspect ratio, which gives the confessional sequences a somber austerity, the reels fizzling out and fading as if we’re watching these melancholic ghosts on the edge of deterioration and disintegration.

With Paradise, we are often stuck vis-à-vis with our three main characters, each positioned against a sterile background as if being interviewed by an unseen person. Come to find, where and how these fit into the film’s larger framework is much more mysterious than anticipated, and early hints assist in keeping us on edge as to their fates—there’s little by way to suggest redemption for anyone. Often, characters are positioned in such a way they are cut out or blocked from the frame, which plays into the film’s visual motifs suggesting Helmut and his cohorts are haunted by their actions, recounting grueling testimony of horrible viciousness inflicted on people. Dark phantoms seep out of the woods while Helmut stops to relieve himself, and characters stare off several times, paralyzed by either a trauma they’ve recalled or a hallucination they may have conjured.

The sound design assists this as well—no amount of classical music or braying orchestral sessions can drown out the wails and screams of humans dying en masse nearby. Several key frames show characters besmirched in darkness, and light (or wind) from the windows streams in, or a film projector, slicing through darkness—the characters, (and to the same extent, those of us in the audience) are merely ignorant figures in the dark, casually enlightened in small, broad strokes, and here reflecting ideals or images of their lives past, before perpetually being marred by their roles or unfortunate entrapment in Hitler’s machine. How Simonov hangs on certain images, an empty beach chair, a cigarette on an ant-hill, or Olga’s legs as she dips them into a pool of water, ease us into magical cinematic moments before we are quickly flayed by moments of incredible cruelty.

Centering this magnificently is a formidable performance from Julia Vysotskaya as a Russian princess turned member of the French resistance—her relationship with Helmut isn’t the romanticized fluff of something like Allied (2016)—this is as a persuasive portrait of madness and survival evoked on screen (and Konchalovsky lends just a brief, minute moment of such distressed levity it only curdles the despair), and from an actress who works very infrequently, and usually only with Konchalovsky. Also of note outside of the principles is Vera Voronkova, whose face recalls the aged beauty of an Ingrid Bergman as the kapo, the near thankless position of the barrack’s leader where Olga is prisoner. Newcomer Christian Clauss is also impressive as an Aryan nobleman, whose class anguish feels like he’d been lifted right out of a Visconti lineup.

Konchalovsky and Kiseleva’s screenplay is filled with book-ending coincidences, chance meetings in the concentration camp, such as Olga happening upon the very boys she had thought would define her legacy of rebelliousness against the Nazis, now stuck in the same boat. Similarly, Helmut not only meets up with the one woman from his limited passionate past, but the specter of his cultural ego in the form of Chekov, whose Jewish love interest, a woman who famously rebuffed him and was supposedly the reason for his anti-Semitism, recently was killed in the very concentration camp he’s meant to monitor for its in-house integrity.

Again, much like Son of Saul, Konchalovsky demands a certain amount of suspension of disbelief with these intersections—for what could possibly generate or further dramatic tension in hell on earth? The film was initially known under the title Ray, possibly an allusion to the visual language established by its frequent uses of beams of light—only proving, despite its color scheme, very little about this world or ours can be defined in black and white. With its ironic international title formatted grimly over Olga as she’s shoved unwillingly into a French prison cell for her role in hiding young Jewish children, Konchalovsky’s latest masterwork is a pervasive scream of anguish from the not-too-distant past.

Reviewed on January 7th at the 2017 Palm Springs Film Festival – 130 Mins.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆