Till I Can Get My Satisfaction: Kurosawa’s Striking Psychosexual Marathon

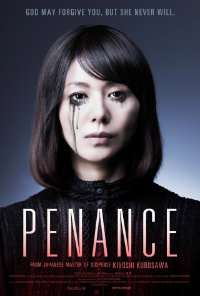

Past traumas hopelessly infecting the present factor significantly in Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s monolithic psychosexual thriller, Penance, a five part made-for-television miniseries that premiered back in 2012 for North American audiences at the Toronto Film Festival, now receiving a limited theatrical release. Like many of Kurosawa’s best known works, he explores the ripple effects of tragic circumstances and their continually endless warping effects, perhaps sometimes seen as a metaphor for cultural tendencies at large. His latest plays like a tangential murder mystery of crossed paths, finally looping back to a finale that leads to more complicated depths, not unlike something David Lynch would do in this similar format of impressively orchestrated subplots and characterizations that makes for viewing in one sitting a head spinning ordeal.

Past traumas hopelessly infecting the present factor significantly in Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s monolithic psychosexual thriller, Penance, a five part made-for-television miniseries that premiered back in 2012 for North American audiences at the Toronto Film Festival, now receiving a limited theatrical release. Like many of Kurosawa’s best known works, he explores the ripple effects of tragic circumstances and their continually endless warping effects, perhaps sometimes seen as a metaphor for cultural tendencies at large. His latest plays like a tangential murder mystery of crossed paths, finally looping back to a finale that leads to more complicated depths, not unlike something David Lynch would do in this similar format of impressively orchestrated subplots and characterizations that makes for viewing in one sitting a head spinning ordeal.

A young girl, Emili, is murdered at school, the killer leading her off in front of four of her young friends, all unable to state what the man looked like afterwards. As the police have no leads and the witnesses are unhelpful, Emili’s grieving mother, Asako (Kyoko Koizumi) vows that the four young girls owe her a penance for letting her daughter die and refusing to assist in catching the culprit.

Kurosawa’s works range from the incredibly heady (Charisma, 1999) to impressively unnerving (Cure, 1997) to the popularly supernatural (Pulse, 2001). Penance, like his similar sounding (at least on the surface) 2006 film Retribution, deals with the aftershocks of murder, depicted as a moment in time that literally poisons the livelihood of all those directly involved. Asako’s binding the four girls to complete a penance for their lack of support in finding the killer is really more of a curse, something that twists their lives into cruel, misshapen reflections of what they could have been. After a fifteen minute intro that finds Asako’s young daughter Emili murdered in the school gymnasium with four of her peers unable or unwilling to describe the man that took her there, we are treated to four forty minute segments revisiting the young women fifteen years later, each at last forced into a situation that allows them to fulfill their penance to Asako.

The first chapter, “French Doll” details a strange romance between Sae (Yu Aoi) and a mysterious and dapper suitor (Mirai Moriyama), who appears out of nowhere claiming to have been enamored with her since their youth. It turns out he has something to do with the rash of French dolls being stolen from households around the time of Emili’s murder. Since then, Sae has chosen to turn herself into a sort of doll modeled after the one stolen from her, a young woman bereft of womanly traits, virginal and repressed.

Next, we move on to Maki’s (Eiko Koike) story, “Emergency PTA Meeting,” wherein the young woman has become a rigid schoolteacher that terrifies her students into conservative submission, her free time spent in fencing practice. Constantly receiving complaints about her strict nature in the PTA, tides are turned when a knife wielding assailant attempts to attack children in the pool one day and Maki uses her skill to subdue him, which gives her temporary status as a hero. But it doesn’t last long. While the segment is more silly than creepy, it reaches heights of absurdity within its realm of nightmarish guilt, with Asako appearing once more at the finale to collect her payment of misery.

Then, we turn to the most somber psychologically complex chapter of the ensemble, that of Akiko (Sakura Ando) in “Brother and Sister Bear,” which shows the young woman retreating to a fantasy world in her head where she thinks she is a bear. Locked in a mental institution for a crime, she has asked to speak with Asako, who obliges with a visit. Akiko relays a strange tale involving her brother (Ryo Kase, who gets to play a much nicer protagonist in Hong Sang-soo’s Hill of Freedom, 2014), though Asako feels a bit stingy about granting the poor girl penance for her situation.

The final chapter of the four girls involves Yuka (Chizuru Murakami), a mildly amusing sociopath who challenges Asako’s promise. Pregnant from her sister’s husband (a bizarre situation that could have been an entertaining film on its own), Yuka happens to hear a voice on the radio that she recognizes as that of Emili’s killer. Seeking out Asako, she attempts to wheedle the woman by stating she will give her information about the killer if Asako will permit Yuka to seduce and marry Asako’s husband. Unfortunately for Yuka, she lapses into premature labor, making her vulnerable to Asako, who watches the woman writhe on the floor akin to that of Bette Davis watching Herbert Marshall bite the dust in The Little Foxes (1941). Eventually Asako relents and assists Yuka, which prompts the selfish young woman to share her clue.

This leads to the finale, a whole hour at last devoted to the greatest asset of Penance, the cruel and imperious mother played by Kyoko Koizumi (who starred in Kurosawa’s retreat from genre, Tokyo Sonata, 2008). It turns out that Emili’s death has roots in dastard deeds of Asako’s own doing, highlighting an elaborate ripple effect. Devoid of any real catharsis, it is Kurosawa’s painstaking orchestration of theme and varied tones that make Penance a real treat. Having released two other titles since then, including the woefully undistributed and highly intriguing Real, as well as Seventh Code (which picked up an award at the 2013 Rome Film Festival), the highly prolific Kurosawa shows no signs of fatigue with this impressively staged genre concept.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆