Examining Eyes, Hearts & Minds: Oppenheimer Sees This Time From The Viewpoint of the Victims

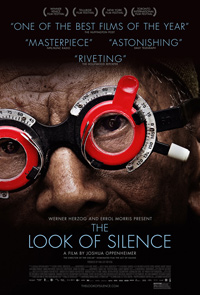

Joshua Oppenheimer rocked the world of cinema with his groundbreaking debut fever dream, The Act of Killing, which bore witness to former Indonesian death squad leaders boastfully admitting to the murder of countless government labeled “communists” via the reenactment of such events in the style of classic American movies which they looked to for inspiration. His Venice Grand Jury Prize winning follow-up, The Look of Silence, takes an even more sobering stance on the subject, this time reflecting on Indonesia’s unique political circumstance from the perspective of those whose friends and family were killed by the murderers who are still in power and continue to live among the community they are forced to share. Less formally daring than its predecessor, yet even more emotionally involving, Oppenheimer’s latest film is, in a word, shattering.

Joshua Oppenheimer rocked the world of cinema with his groundbreaking debut fever dream, The Act of Killing, which bore witness to former Indonesian death squad leaders boastfully admitting to the murder of countless government labeled “communists” via the reenactment of such events in the style of classic American movies which they looked to for inspiration. His Venice Grand Jury Prize winning follow-up, The Look of Silence, takes an even more sobering stance on the subject, this time reflecting on Indonesia’s unique political circumstance from the perspective of those whose friends and family were killed by the murderers who are still in power and continue to live among the community they are forced to share. Less formally daring than its predecessor, yet even more emotionally involving, Oppenheimer’s latest film is, in a word, shattering.

A warmly reserved and headstrong optometrist named Adi, whose brother was one of the thousands slain at the hands of the death squads and whose son is now being taught in school by the men who took part in the mass killings, serves as film’s central character and emotional core. He was only a child when the events took place, but over the last few decades he’s gleaned bits and pieces of his brother, Ramli’s story from his chatty visits to those in his community needing their eyes checked. Most people, afraid of what acknowledging the horrors of the past will inspire, clam up, repeating the local mantra, ‘The past is past,’ never letting the tension in the air settle.

These eye exams serve two cinematic purposes: 1) To compose a beautiful metaphor for the search for historical clarity. 2) To provide the safest, most organic way for Adi to do what in the current political climate of Indonesia is thought to be unthinkable – in face to face conversation, ask known death squad leaders to admit their guilt and acknowledge what they did was morally wrong.

Thanks to Oppenheimer’s lengthy filmmaking relationship with these men, they are able to set up each meeting under the pretense that these men need their eyes checked. Simple in premise, but deathly serious in practice, each interview was setup so thoroughly that according to Oppenheimer, get away vehicles and flights out of the country for Adi and his family were purchased in advance just in case things went awry. These are intense, heartbreaking, horrifying conversations, yet Audi handles them without raising his voice, somehow managing to separate the withering human before him and the atrocities he once committed.

Edited within these confrontations are extended sequences of the same killers that come under Adi’s questioning, gleefully admitting to torturing their victims and drinking their blood (as not to go crazy from killing too many) before dumping their mangled bodies in the Snake River. A pair of these men get into grotesque detail about how they took pleasure in ending Ramli’s life. They claim he was stabbed several times in the ribs, his stomach opened up, but he somehow managed to escape, crawled through rice paddies and made it home before being taken once again. His mother was told he was being escorted to the hospital, but instead he was dragged, bound and beaten to the river bank where they removed his genitals and was thrown to his watery grave. The Act of Killing was a fully stocked hall of horrors, but nothing in its lengthy running time tops the heartlessness on display here.

Adi’s continuously audacious bravery is incredible to behold, and what’s more is his warmth and empathy within his method of attack. His inquisitions first test the depths of admission before dropping the bomb that they may be responsible for not only the murder of his brother, but the pain and suffering that continues to seethe within him, his family and the community at large.

Among the many shocking sequences that make up the astounding, crucial work that is The Look of Silence, Adi’s father, now 103 years old, blind and senile, remains the most haunting imagery in the film. Scrambling about in the dark behind his eyelids, terrified, the old man is filmed by his own son as he calls out for help, lost in what he believes to be a stranger’s abode. Like this man, there are generations of innocent Indonesian victims trapped within metaphoric walls where remembrance is fear itself. The past is not past, but present until admission and forgiveness is a viable option.

Reviewed on September 7th at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival – TIFF Docs Programme. 98 Minutes

★★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆