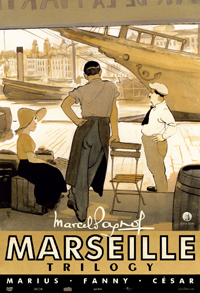

In 2017’s first major (and highly impressive) restoration, Janus films breathes new life into novelist/playwright/director Marcel Pagnol’s indelible Marseille Trilogy, a triptych of films each helmed by different auteurs in 1930s France, standing as the most effective Provencal saga ever committed to film (even though the material has been adapted several times for theater and television in the decades since). Beginning with 1931’s Marius, followed by 1932’s Fanny, and 1936’s Cesar (which Pagnol also directed, by then a notable filmmaker himself), the three indistinct chapters play like a seamless and immersive experience in its depiction of a way of life during a particular time period. Simple but sincere, Pagnol’s attenuated dialogue unfolds as if in real time with an authenticity quite rare for adapted stage plays. Gorgeously restored, the original trilogy has finally been made available in all its craftily detailed glory.

In 2017’s first major (and highly impressive) restoration, Janus films breathes new life into novelist/playwright/director Marcel Pagnol’s indelible Marseille Trilogy, a triptych of films each helmed by different auteurs in 1930s France, standing as the most effective Provencal saga ever committed to film (even though the material has been adapted several times for theater and television in the decades since). Beginning with 1931’s Marius, followed by 1932’s Fanny, and 1936’s Cesar (which Pagnol also directed, by then a notable filmmaker himself), the three indistinct chapters play like a seamless and immersive experience in its depiction of a way of life during a particular time period. Simple but sincere, Pagnol’s attenuated dialogue unfolds as if in real time with an authenticity quite rare for adapted stage plays. Gorgeously restored, the original trilogy has finally been made available in all its craftily detailed glory.

If Marius or Fanny are film titles which seem familiar to contemporary art-house auds, it would most likely be thanks to actor Daniel Auteuil, who directed remakes of the first two installments in 2013 (with his rendition of Cesar still supposedly on the way). Auteuil got his feet wet adapting Pagnol in 2011 with The Well Digger’s Daughter, a similarly structured story about a beautiful young peasant woman who becomes pregnant out of wedlock, much to her father’s violent chagrin. The Marseille Trilogy seems to have aged somewhat better, in that it’s socially conservative mores of the period are less harshly dictated, and the focus is rather on the thwarted romance between its central characters, a combination of self-inflicted martyrdom mixed with traditional expectations. While not quite the deplorable heights of Greek tragedy, this six-hour plus saga manages to remain compelling on this sole simmering notion, where cuckolding and incestuous nightmares haunt the periphery.

Pagnol’s trilogy begins with its most notable director, Alexandre Korda, the Hungarian born British filmmaker who would come to be known for his English language features (the Vivien Leigh headlined That Hamilton Woman, 1941). Marius sets the tone for the domestic tragedy threading the trilogy together, and takes its time establishing the characteristics of the ornery but jovial bar owner Cesar (a winning performance from Raimu), his disinterested son Marius (Pierre Fresnay), and the latter’s troubled romance with his childhood sweetheart Fanny (Orane Demazis), a cockle monger alongside her mother Honorine Cabanis (Alida Rouffe), a woman more concerned with avoiding scandal more than anything else. Prosperous sail maker and lonely widower Panisse (Fernand Charpin) has his sights set on Fanny’s hand despite their concerning age difference. Marius must decide on saving Fanny from a humdrum life by marrying her or pursue his actual love, a life of adventure on the seas. Fanny knows of his real dream, and she pushes him to realize it…but not before getting pregnant, unbeknownst to Marius. The virtue of womanhood is at stake in the film’s moral center. “Honor is like a match, it can only be used once,” is a foreboding reference to the consequences both Marius and Fanny must face.

In the 1932 sequel Fanny, director Marc Allegret takes over to document the fallout of Marius’ decision to abscond. Cesar spends the first portion of the film distraught at having been left by his son (Fanny doesn’t even pop up for the first half hour), seeking solace in their loneliness together. But the nagging problem of Fanny’s pregnancy brings Panisse’s proposition back into play. Cesar is against their marriage, vowing to rear Fanny and the child himself (neither are too keen on telling Marius, who leaves mention of Fanny out of his letters to dad as he writes home). For the sake of the child, Fanny accepts Panisse’s proposal, who knows the child isn’t his (he wasn’t able to conceive with his first wife, further making Fanny more lucrative). Blunt conversations about cuckoldry ensure—Panisse knows he isn’t a catch for Fanny, but her pregnancy out of wedlock has lowered her social worth as well.

Pagnol himself steps in to direct 1936’s final chapter, Cesar, which opens nearly two decades where we left off with Fanny. Panisse is on his deathbed, though jocular as always, dismayed the priest makes a sudden appearance even before his diagnosis isn’t dire enough to warrant the visit just yet. We find the once fraught relationship between Cesar and Panisse easily smoothed over, although neither of them want to tell Cesariot (Andre Fouche) that Marius is really his father and Cesar his grandfather. Fanny eventually breaks the news, which causes immediate conflict between mother and son. The film takes on the tone of screwball comedy when Cesariot takes a secret visit to see Marius, now a mechanic in Toulon, under the guise of a journalist, while Fanny and Cesar hire a boatswain to spy on him, thinking he is meeting a young woman in secret. Pagnol’s directed chapter happens to be one of the more visually innovative, utilizing swipe transitions and offering a bit more jaunty energy thanks to shifting locales (as compared to the static sequences of dialogue in the earlier two films). Eventually, Cesar leads us to the

Despite its simplicity, Pagnol’s Marseille Trilogy is a richly textured character driven triptych of films detailing a certain time, place, and sentiment. As several remakes can attest, the difficulty in re-capturing Pagnol’s particular mise-en-scene has not been accomplished in any of the adaptations since.

Marius Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Fanny Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Cesar Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆