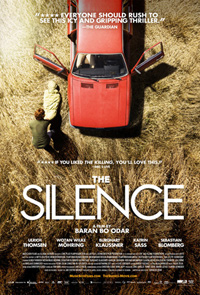

History of Violence: Odar’s Debut a Sweaty, Slow Burn

Swiss director Baran Bo Odar adapts Jan Costin Wagner’s novel The Silence for his film debut, a murder mystery thriller filmed in 2010, finally getting a much deserved theatrical release. Filmed in Germany and featuring a multitude of notable European names, including the presence of Danish actor Ulrich Thomsen, whose presence lends an odd twist to the proceedings, Odar’s film feels akin to a number of Scandinavian genre exercises that have been produced over the last several years. But whereas most thrillers focus on unraveling culprits, Odar’s film is an examination of ‘why’ terrible deeds happen, exposing a host of characters that are expertly developed, sometimes at a detriment to the pacing.

Swiss director Baran Bo Odar adapts Jan Costin Wagner’s novel The Silence for his film debut, a murder mystery thriller filmed in 2010, finally getting a much deserved theatrical release. Filmed in Germany and featuring a multitude of notable European names, including the presence of Danish actor Ulrich Thomsen, whose presence lends an odd twist to the proceedings, Odar’s film feels akin to a number of Scandinavian genre exercises that have been produced over the last several years. But whereas most thrillers focus on unraveling culprits, Odar’s film is an examination of ‘why’ terrible deeds happen, exposing a host of characters that are expertly developed, sometimes at a detriment to the pacing.

In the sweltering July sun in 1986, an 11 year-old girl named Pia is raped and murdered by Peer Sommer (Thomsen) as she crosses through a field on her bicycle. Peer’s friend and accomplice, Timo (Wotan Wilke Moehring) watches in anguish from Peer’s car, helping him clear up the aftermath. Pia’s mother (Katrin Sass) is left broken and alone, her daughter’s case unsolved. Now, twenty three years later, another young girl, Sinikka, is murdered in the same fashion and in the exact same spot as Pia, which sends the small German community reeling once again, desperate to discover if this is the return of a serial killer or a ruthless copycat.

Recently widowed detective David (Sebastian Blomberg) and his pregnant colleague Janna (Jule Boewe) are assigned the case, both of them at first focusing more on their significant personal situations than the case at hand. Meanwhile, the retired detective from Pia’s case, Krischan (Burghart Klaussner) attempts to be involved with the investigation, much to the chagrin of everyone else. And once the news story hits the media, Timo, who ran away from his friend back in 1986, is alerted, and he now has a wife and children of his own. The news of Sinikka unnerves him to such a degree that he makes his way back to Peer, once again faced with the possibility on acting on desires he has so desperately tried to keep at bay.

There’s an oddly suspended tension laced throughout The Silence, which thankfully keeps our interest even through a rather uneventful middle portion of the film, where a revolving door of characters and all their pent up emotional situations eclipse the focus of the film. While the killers are revealed in the very first frames in a gorgeously shot and uncomfortable sequence utilizing high angles and crane shots from cinematographer Nikolaus Summerer, (which switches directly to ground, earthbound shots as immediately as the narrative switches to present day), it’s their odd dynamic and only subtly defined motive that sets The Silence a cut above similar fare.

If you’re familiar with Thomsen’s incendiary turn in 1998’s The Celebration, his disposition as a warm and friendly pedophile here feels even more significant, as his Peer Sommer is definitely the least conflicted character. The rest of the key players are all significant actors with some major titles to their credits, each disappearing into well rounded and intelligently written characters. Bleak and corrosive, The Silence neither judges nor vilifies, but instead is a unique and compelling portrait of loneliness. Odar smartly avoids patronizing us, and while it definitely could have trimmed a good twenty minutes from its middle portion, The Silence never sells us short, instead giving us one final closed door in the face.