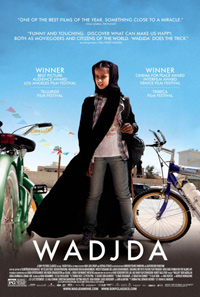

The Kid Without A Bike: Charming Ride Through Gender Politics in the Middle East

Even before the film appears on the screen there is a sense of added importance that permeates it. Just on the ground that this is not only the first ever feature film from a female Saudi Arabian director but also the first ever to be shot entirely inside the country, should makes this an event. Movie theaters are banned in the Middle Eastern Kingdom, and women live under highly restricted circumstances that forbid them even from driving, such facts make of Haifaa al-Mansour’s film a defiant move, even a political statement. But to judge a film solely on the politics that surrounded its production would be unproductive; however, with a work like Wadjda that is not necessary since it shines on its own merits.

Even before the film appears on the screen there is a sense of added importance that permeates it. Just on the ground that this is not only the first ever feature film from a female Saudi Arabian director but also the first ever to be shot entirely inside the country, should makes this an event. Movie theaters are banned in the Middle Eastern Kingdom, and women live under highly restricted circumstances that forbid them even from driving, such facts make of Haifaa al-Mansour’s film a defiant move, even a political statement. But to judge a film solely on the politics that surrounded its production would be unproductive; however, with a work like Wadjda that is not necessary since it shines on its own merits.

The title character, 10-year-old Wadjda (Waad Mohammed), seems unaffected by the cloud of machismo and Islamic limitations that cover her environment. She attends an all-girls school, as mandated by the religious establishment, but that doesn’t prevent her from having a young male friend Abdullah (Abdullrahman Algohani), whose bicycle becomes her object of desire. Not only does Wadjda need to figure out how to get the money for a bike, but also how to go around the ingrained belief that girls should not ride them because they risk their sacred virginity. That is why a situation that could be deemed a mundane premise in the Western world becomes a norm-challenging story, in which via the simplicity of a childhood desire other more profound concerns about civil liberties for women are expressed.

Wearing purple sneakers, listening to rock bands on the radio, and devising ingenious scams to achieve her goal, Wadjda separates herself from the rest of the girls. Her mother (Reem Abdullah) is conservative but never fully oppressive, she understands the parameters by which they must exist, but seems to find hope in her daughter’s actions, and that is the true spirit of the film, hopeful. Women must endure long drives to their place of employment and pay to be driven around to comply with the submission that is expected from them, such lack of freedom of mobility reinforces the significance for a young girl to have access to a bicycle. Yet, for all the support at home, Wadjda is faced with the realities of her gender at school. Girls her age are ready to be married off, little girls are guilt for standing in the view field of men, and others are accused of indecent conduct for holding hands.

This is a hard world to live in for a girl who has not been tainted with insecurity or self-pity, not once is Wadjda seen surrendering her individuality or giving in to what adults tell her is the right place for a girl. Young Waad Mohammed infuses Wadjda with mischievous heart-warming quality. She is a rascal and a sweetheart at once, one that will stop at nothing to get her cherished ride but who also feels utter love and respect for both of her parents, even if their relationship is doomed by the common practice of polygamy. It is outstanding how Haifaa al-Mansour was able to conceive a fantastically multilayered screenplay that pushes the boundaries of what femininity means not only in the extremely traditional society of Saudi Arabia but in the entire region.

Wadjda’s definitive plot to obtain the money she needs for her bicycle, which has been on a sort of layaway system by the local toy vendor, is to win her school’s Quran reading and trivia contest. She is determined to succeed and devotes her time to learning and practicing it, certainly for her ulterior motives, but nonetheless she learns, and she is rewarded for it. That is probably the director’s biggest achievement, by utilizing all burdens and troubles not as fixed punishments but as obstacles to overcome, she has made a film that speaks of woman in her country as intelligent, ambitious, and creative individuals who are not less virtuous in the religious sense by being so.