The Boys in the Choir: Polk’s Antiquated Rendition of the Rural Gay Narrative

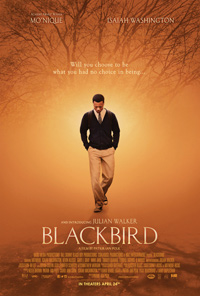

The blatant underrepresentation of black gay characters in film, whatever letter they’re placed into on the inclusive LGBT spectrum, is simply not reason enough to appreciate the elemental contrivances of Patrik-Ian Polk’s Blackbird, an independent film rife with cliché in its euphemistic depiction of the rural queer experience that does little to elevate the film’s archaic nature.

The blatant underrepresentation of black gay characters in film, whatever letter they’re placed into on the inclusive LGBT spectrum, is simply not reason enough to appreciate the elemental contrivances of Patrik-Ian Polk’s Blackbird, an independent film rife with cliché in its euphemistic depiction of the rural queer experience that does little to elevate the film’s archaic nature.

The title has been inadvertently thrown into a higher caliber pop culture zeitgeist thanks to its distinction as Mo’Nique’s first post-Oscar role since her 2009 win for Best Supporting Actress in Precious. The significant media coverage concerning potential fallout between herself and director Lee Daniels should enhance the film’s shelf-life beyond the trappings of a niche market. Produced by the actress and her agent/husband Sidney Hicks, the project feels very much like the well-intentioned labor of love they meant for it to be, albeit one marred by a series of unfortunate creative choices that render the film’s emotional potential inert.

Known for his popular and groundbreaking 2004 television series “Noah’s Arc,” Polk is one of a select few names consistently committed to the portrayal of black gay men with his output, graduating to film with Noah’s Arc: Jumping the Broom in 2008 and The Skinny in 2012. He’s switching gears here with Blackbird, intriguingly based on a 1986 novel by Larry Duplechan, adapted by screenwriter Rikki Beadle Blair (also a multi-talented voice in gay indie film, directing and writing in starring in his own features, such as 2010’s KickOff). But Polk and Blair don’t seem quite adept at mounting melodrama, and Blackbird often plays like a regressive artifact of first stage queer film.

Polk also injected a bit of his own biography into the proceedings, filmed in his hometown of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, which perhaps lends the film a detached, period feel. Randy and Efram are fairly stereotypical, each residing on one side of the virgin/whore dichotomy often used to differentiate between female archetypes in cinema.

Kudos to Mo’Nique’s portrayal of religious fanaticism as the mental illness it looks and sounds like, but unfortunately her Claire Rousseau devolves into the wrong kind of camp, another wacky, weird, abusive matriarchal figure. Bashing into her son’s boyfriend’s car with a baseball bat, Mo’Nique roils into a religious fury reminiscent of Margaret White in Carrie, afraid of the uncontrollable, natural sexuality of her progeny.

Isaiah Washington strikes a more appropriate figure as Randy’s liberal minded father. This portrait of southern, familial angst could have been more successful had we left behind several tangents, notably the kidnapping of Randy’s younger sister, which his mother cites is God’s punishment of the family for his gayness—a line of thought magically rationalized at the finale.

Add to that an incredibly underdeveloped subplot involving Randy’s second sight and a whole host of gay rites of passage squeezed through a fantasy template, and Blackbird feels like a television season cut into one extended special. It doesn’t help that filmmaker John Cassavetes, the Godfather of Independent Film, gets name dropped in here.

Blackbird often looks more accomplished than it sounds, and some very talented younger performers struggle to overcome contrivance, such as actors playing Randy’s friends, like Nicole Lovince and Gary LeRoi Gray (who might have made a better Randy). Newcomer Julian Walker’s performance often feels like we’re watching high school theater, and isn’t up to the task of portraying the subtleties needed for a conflicted character such as Randy. Perhaps in decades past, a coming of age tale like this would have made sense, where Randy’s (slightly) older lover would initiate him into the world of secret sexcapades of the promiscuous lives of gay men (once again portrayed as punishable lifestyle replete with STDs and eventual drug addiction that chaste characters nimbly bypass), but by today’s modern standards, this routine isn’t filtered through these same channels.

It’s with great misgivings that one cannot endorse the good intentions of a film like Blackbird, as content featuring characters like Randy, set within the staunchly conservative world of religious black communities, needs to be made more often and more prominently for our consumption. And perhaps Polk’s adaptation is a film meant for them, those people living in a fantasy world where it’s appropriate to condemn people based on who they want to love. But we’ve moved beyond a point where intentions aren’t enough, and the familiar floridness of Blackbird renders it both inarticulate and flimsy, especially if compared to recent fare like Dee Rees’ beautiful Pariah (2011).

★½/☆☆☆☆☆