Reviews

Padre Padrone | Taviani Retrospective Review

I Never Sang for My Father: The Taviani Brothers and the Prison of Patriarchy

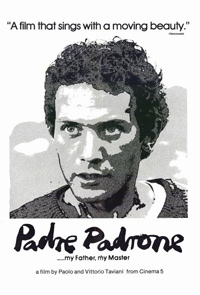

For many, Italian directing duo Paolo and Vittorio Taviani are best remembered for their output from the late 70s to late 80s, coming to prominence on the international circuit and unveiling a string of notable titles before falling out of critical favor by the mid-1990s. In 2012, the brothers made a resurgence winning the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival, which resulted in bringing their old classics back to new, contemporary audiences. A retrospective featuring new restorations of three important titles begins with one of their most lauded films, 1977’s Padre Padrone, which took home the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival (notably, Roberto Rossellini was the jury president, whose 1946 film Paisan inspired the brothers as filmmakers). Based on a memoir (Gavino Ledda’s The One That Got Away) and originally intended for television, the neo-realist imbibed bildungsroman is a powerful denunciation of patriarchy as well as a testament to the power of education.

For many, Italian directing duo Paolo and Vittorio Taviani are best remembered for their output from the late 70s to late 80s, coming to prominence on the international circuit and unveiling a string of notable titles before falling out of critical favor by the mid-1990s. In 2012, the brothers made a resurgence winning the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival, which resulted in bringing their old classics back to new, contemporary audiences. A retrospective featuring new restorations of three important titles begins with one of their most lauded films, 1977’s Padre Padrone, which took home the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival (notably, Roberto Rossellini was the jury president, whose 1946 film Paisan inspired the brothers as filmmakers). Based on a memoir (Gavino Ledda’s The One That Got Away) and originally intended for television, the neo-realist imbibed bildungsroman is a powerful denunciation of patriarchy as well as a testament to the power of education.

While in his first year of primary school, Gavino Ledda (Fabrizio Forte) is yanked out of class by his ornery father Efisio (Omero Antonutti), who demands his son’s help looking after his sheep, their poverty trumping the need for an education. Never allowed to return to school again, Gavino grows up in desolation, desperately reaching out to animals and other humans he crosses paths with (including a duo of accordion playing thieves). When he becomes of age (now played by Severio Marconi), Gavino’s father enlists his son in the Italian army where the young man meets a comrade (Nanni Moretti) who teaches him how to read and speak proper Italian. Gavino proves to have an aptitude for learning and plans to leave the army to pursue a degree in dialects. But this proves easier said than done when he’s forced to return to Efisio and contend with his father’s ignorance.

“Poverty is all that’s compulsory,” barks Gavino’s father, wrapping his walking stick at the school teacher as he extracts his son for good from school. He further chastises the laughing children, warning their turn is next. This moment is looped back to in the final frames, indicating a warning beyond the frame—through Gavino Ledda’s impressive tenacity (who appears within the film to introduce and conclude), he managed to overcome the handicaps of rural isolation, but this will not be the case for most children born into similar scenarios. The Tavianis’ title is a play on language (the translation being Father and Master), highlighting the similarity between labels with overlapping connotations.

While Sardinia takes on a sort of glacial beauty around him, we realize immediately how stunted Gavino’s life has become, evidenced in the eluding of thrashes from his abusive father. More uncomfortably, the directors don’t shy away from the sexual realities of such an existence, with many young boys experiencing their first coital moments with animals. A creative voice-over represents young, inarticulate Gavino’s interactions with the world, imagining an argument with the goats who cruelly defecate in the milk he collects (resulting in more moments of animal abuse).

As Gavino grows, an expressive performance from Saverio Marconi elicits great sympathy, particularly in a final showdown where he must finally take leave of his father’s homestead. A tender caress morphs immediately into a gesture of implied violence. Speech and what’s depicted as the privilege of agency becomes a subconscious motif, for Gavino grows up being nearly mute, and again loses his voice upon returning to his father’s farm as an adult. Having grown up only speaking Sardinian, a dialect of Italian, he can’t effectively understand his commanding officer in the army.

Among the supporting cast, a young Nanni Moretti co-stars as Ledda’s comrade who initially gives the young man lessons so he can communicate, while DP Mario Masini (who had a varied filmography, including works of animation and the famous giallo The Perfume of the Woman in Black, 1974) brings the film out of barrenness into a graceful achievement for Ledda. At its most potent, this ‘freely depicted’ portrait of Ledda’s life shows the possibility of breaking free from a continuous cycle of disadvantage.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Los Angeles based Nicholas Bell is IONCINEMA.com's Chief Film Critic and covers film festivals such as Sundance, Berlin, Cannes and TIFF. He is part of the critic groups on Rotten Tomatoes, The Los Angeles Film Critics Association (LAFCA), the Online Film Critics Society (OFCS) and GALECA. His top 3 for 2021: France (Bruno Dumont), Passing (Rebecca Hall) and Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro). He was a jury member at the 2019 Cleveland International Film Festival.