Munster’s Ball: Ivory’s First Crack at James is Ripe for Restoration

Arguably, Henry James, the famed American author whose most notable acclaim was received in his later years at the turn of the century, could be classified as an ‘acquired taste.’ Master of the compound sentence, in direct opposition to the spare ‘American’ style popularized several decades later by the likes of Hemingway, James style is distinctive across his body of work, often dealing with Americans confounded and flabbergasted by their interactions with expatriates and Old World Europe, often floundering or suffocating under the weight of rigid social customs and expectations.

Arguably, Henry James, the famed American author whose most notable acclaim was received in his later years at the turn of the century, could be classified as an ‘acquired taste.’ Master of the compound sentence, in direct opposition to the spare ‘American’ style popularized several decades later by the likes of Hemingway, James style is distinctive across his body of work, often dealing with Americans confounded and flabbergasted by their interactions with expatriates and Old World Europe, often floundering or suffocating under the weight of rigid social customs and expectations.

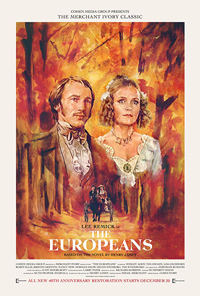

Cohen Media Group continues to unspool its rich restorations of the Merchant Ivory collection, re-releasing what’s perhaps considered both a minor James novel as well as an obscured title from James Ivory—the 1979 adaptation of The Europeans. In many ways, it was this film which established the Merchant Ivory brand, re-creating classic literature with sumptuous attention to detail. It was the first of Ivory’s six films to compete at Cannes (his last would be his 2000 adaptation of The Golden Bowl, his final James adaptation) and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Costume Design. In Ivory’s catalogue, it is perhaps his 1984 adaptation of James’ The Bostonians which best withstood the test of time in comparison to his more lauded E.M. Forster classics, such as Howards End (1992), Maurice (1987), or A Room with a View (1985).

Baroness Eugenia Munster (Lee Remick) and her brother Felix Young (Tim Woodward, son of Edward Woodward) arrive unexpectedly from Europe to visit their American cousins who live in the Boston suburbs. It’s the 1850s and the Baroness’ husband, an apparently mercurial prince, is attempting to dissolve their marriage, which would leave her, sans a title, merely penniless. Their visitation upon the Wentworth house is met with a sense of innate wonder by the children of the family, including the increasingly wayward Clifford (Tim Choate) and his sisters Charlotte (Nancy New) and the tempestuous Gertrude (Lisa Eichhorn). Their father (Wesly Addy) seems less inclined to accept them without question. Budding pastor Mr. Brand (Norman Snow) has been futilely pursuing Gertrude, who takes an immediate fancy to Felix. Meanwhile, Eugenia carries on a troubling (according to their parents) friendship with Clifford and Robert Acton (Robin Ellis), one of the cousins from the other side of the Wentworth tribe. Robert and his dubious sister Lizzie (Kristin Griffith) have a sizeable inheritance at their disposable, but it would seem Felix secures a future much more quickly than Eugenia, who is forced to make a rather unenthusiastic decision.

Based on James’ 1878 novel, which the author himself classified as “A Sketch,” James and usual scribe Ruth Prawer Jhabvala stick close to the template of the text, with many passages of dialogue lifted freely from its pages. The opening credits belie this sentiment, a series of hand sketches reflecting the essence of the quiet solitude of Boston suburbia in the mid-nineteenth century.

Just as James’ novel was a sketch (and as such, is much shorter than his later tomes afforded his most famous characters), so does Ivory’s film depend on the superficiality of the narrative, which finds a group of rather rigid Americans brought to romantic precipices by the arrival of their colorful European cousins, a brother and sister looking to retain their titles but seek an economic stability about to be torn away from them.

As in the novel, one cannot believe in either of their motivations, and there remains a sinister specter of suspicion, vocalized only by two of the American elders who have lived long enough to take this unexpected visitation at more than face value. But Ivory’s film, like the novel, does little to guide us between the lines, and while on its surface The Europeans is a series of amusing vignettes, its autumnal beauty ends with a chill of missed calculations for one sibling and a doomed yielding of freedom for the other.

As the troubled Baroness Munster, Lee Remick is arguably too beautiful (not unlike Julie Christie in Schlesinger’s Far From the Madding Crowd), and one of the few departures from the text allows Ellis as her enchanted suitor to fantasize about her capriciousness (and altogether untrustworthiness based on her actions and penchant for little white lies). Tim Woodward is allowed to be a bit more lively as her brother Felix, a young man adrift but seizes, perhaps a bit too conveniently, on the chance of marrying the black sheep of the Wentworth’s. His passages with Lisa Eichhorn’s Gertrude tend to focus on how they are both ‘strange,’ and it’s her inability to ‘understand’ Felix, or perhaps his motivations, which remains transfixing to her.

Although superficially predictable, and its two relationships (and one failed one) which make up the third act, The Europeans might not seem to be about anything, an argument lobbed at several of James’ texts. But like his famed The Turn of the Screw, this is an exercise in dueling perspectives, and beyond the tenets of their culture, nothing really defines either the Americans or the Europeans beyond the former group seemingly existing in a dull vacuum and the latter seeking a way to ensure their continued survival.

The idea of no one questioning (besides the brief dismay of Addy’s enjoyably stern patriarch) the union of Felix and Gertrude, or the inevitable dysfunction which will arise out of her former suitor Mr. Brand marrying her sister Charlotte, points to the naiveté of these quiet Americans and the sinister machinations of the Baroness and her brother. Likewise, as the Emerson-reading invalid Mrs. Acton, Helen Stenborg perhaps walks away with the only authentically emotional sequence in The Europeans, knowing her son’s feelings for the Baroness and attempting to delay her departure for him despite her disinterest in a woman her daughter has painted as pretentious and worldly.

Beautifully photographed by Larry Pizer, The Europeans conveys an unstated death pallor which overshadows its otherwise jaunty proceedings. We can never really get to know the Baroness and her brother because to do so would mean they’d reveal their true intentions, which might be something they can’t succinctly define—and this dollop of James’ Bostonians formulates a culture too afraid to know itself—not even enough to protect itself from the more pleasant of parasites.

★★★/☆☆☆☆☆