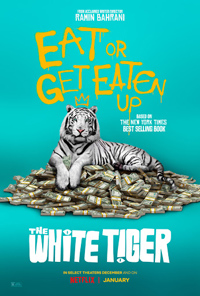

Caste Him If You Can: Bahrani Returns with Genre-Tinged Social Issue Saga

American filmmaker Ramin Bahrani remains an unpredictable cinematic master, a signature of his output ever since his arrival on the festival circuit in the late 2000s, when Roger Ebert hailed his 2007 sophomore film Chop Shop as one of the best films of the decade, all the way through his last offering, the HBO produced remake of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (2018). Over a decade later, Bahrani’s interests may seem to fluctuate in a superficial sense but are also intriguingly linked.

American filmmaker Ramin Bahrani remains an unpredictable cinematic master, a signature of his output ever since his arrival on the festival circuit in the late 2000s, when Roger Ebert hailed his 2007 sophomore film Chop Shop as one of the best films of the decade, all the way through his last offering, the HBO produced remake of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (2018). Over a decade later, Bahrani’s interests may seem to fluctuate in a superficial sense but are also intriguingly linked.

His latest film The White Tiger, an adaptation of the 2008 novel by Aravind Adiga, brings the director to India, a country whose cinematic output remains associated with Bollywood productions (although several arthouse directors have risen to acclaim over the past decade, including Anurag Kashyap and Chaitanya Tamhane, among others). Although it has enough going on to satisfy those who appreciate the fodder of soap opera, it’s another interesting class-conscious melodrama which is bolstered by an empathetic lead performance from Adarsh Gourav.

Balram Halwai (Gourav) is born into a low caste in a rural Indian village. While he shows promise as a student and is invited to pursue a higher education, he’s instead forced into assisting his father’s business, an establishment forever indebted to the wealthy family controlling all operations of the community, lorded over by a man known as The Stork (Mahesh Manjrekar of Slumdog Millionaire, 2008). The Stork’s eldest son The Mongoose (Vijay Maurya) is a particular terror to the villagers, and his father’s eventual demise leads Balram to remain a provider for his extended family, controlled by the family matriarch (Kamlesh Gill). When The Stork’s youngest son Ashok (Rajkummar Rao) returns from New York alongside his new bride Pinky (Priyanka Chopra), Balram sees a chance to become a driver for the new young master.

Finagling his way into driving lessons through empty promises, Balram manipulates his way into the family and attempts to ascend the hierarchy amongst the servants. Ashok and Pinky don’t believe in the same values as their elders, attempting to educate Balram about the ways of the world, blurring lines of authority and friendship. When Pinky is involved in a tragic accident of her own causing, the family sets up Balram as the scapegoat for her actions. Narrating his own story from the vantage point of safety and success, Balram relays how this incident eventually opened his eyes to the falsehoods instilled by his culture, the brainwashing of the lower castes to behave as caged roosters, resigned to their fate of subservience.

The White Tiger plays like the third chapter in a thematically related trilogy from Bahrani, which began with 2012’s At Any Price, a sort of Arthur Miller-esque tale set in American farm country. Likewise, 2014’s 99 Homes, a formidable social drama/thriller addressing those caught on opposing sides of the US housing crises. His latest plays like a kissing cousin to Richard Wright’s classic novel Native Son, at least in how a dramatic catalyst of a “servant” involved in a murder and its aftershocks are predicated on a hierarchy of human worth. But the framed narrative, which posits Balram as the titular ‘once-in-a-generation’ natural anomaly, makes efforts to show how he’s also stuck in cultural cage. Collapsing the analogy of India’s lower castes as being brainwashed by a rooster-cage mechanism, a visual parallel with Balram visiting a white tiger at the zoo cements Bahrani’s obvious commentary.

A framed narrative, which finds Balram narrating his own story, supposedly as a chance to present himself to a visiting Chinese businessman in Delhi, somewhat robs the film of its potential tension and anxiety, but this hardly seems to matter. Although with a running time topping two hours, it seems a pity we couldn’t explore some of the more tangential characters even as Bahrani does his best to include their energies. If The Stork and The Mongoose are simply vile representatives of the privileged, the manipulations of both Balram’s grandmother and The Great Socialist (Swaroop Sampat) are intriguing females using what power they have for survival through control. Instead, we’re left to dissect the troubling nexus of Ashok and Pinky, representative of a liberal minded younger generation adopting views of the West who are irrevocably compromised by their inability to see how they are a complex part of the same problem.

If Priyanka Chopra is utilized sparingly, whose presence in the cast elevates the film’s international attention (same with Ava DuVernay executive producing), it’s really Rajkummar Rao who spends the bulk of the film proving the flaws of being liberal minded without actual empathy or enlightenment. A persuasive score from Danny Bensi and Saunder Jurriaans (“Ozark”; The Devil All the Time, 2020) and moody cinematography from Paulo Carnera (Bad Tales, 2020) aligns the tone with neo-noir, but like with 99 Homes, Bahrani’s choice to hew closer to social and moral dilemmas strikes more of a melodramatic formulation.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆