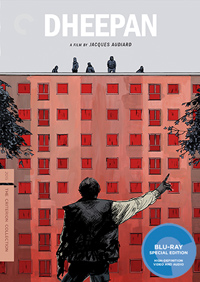

Almost exactly two years after he won the Palme d’Or for Dheepan at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, Jacques Audiard finagles his way into Criterion’s corridors for the first time with his celebrated seventh feature. The five time Cesar winner took home the top prize with his fourth round in the main competition (although he’d previously snagged Best Screenplay for A Self Made Hero in 1996 and the Grand Jury Prize in 2009 for his lauded A Prophet), but the controversial prestige was the result of purported contention among the Coen Bros. led jury, a voting body which seemed more intent on awarding Audiard for touching on topical refugee issues.

Almost exactly two years after he won the Palme d’Or for Dheepan at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, Jacques Audiard finagles his way into Criterion’s corridors for the first time with his celebrated seventh feature. The five time Cesar winner took home the top prize with his fourth round in the main competition (although he’d previously snagged Best Screenplay for A Self Made Hero in 1996 and the Grand Jury Prize in 2009 for his lauded A Prophet), but the controversial prestige was the result of purported contention among the Coen Bros. led jury, a voting body which seemed more intent on awarding Audiard for touching on topical refugee issues.

The downbeat narrative features a makeshift family thrown together as they assume the identities of dead causalities in war torn Sri Lanka. Seeking asylum in France, they’re placed in housing projects facing similar spurts of violent conflict. The film’s distinction didn’t translate into a similar international embrace, resulting in a meager domestic box office when US distributor released the title in May of 2016, while it was not submitted as France’s foreign language submission at the Academy Awards (in its place, Deniz Gamze Erguven’s Mustang was forwarded and went on to receive a nomination).

His family slaughtered, a Tamil fighter (Antonythasan Jesuthasan) is forced to flee Sri Lanka for France. Given papers of a deceased man named Dheepan, he is tossed into a posing as the husband of Yalini (Kalieaswari Srinivasan) and father of teenage daughter Illayaal (Claudine Vinasithamby). All having lost their loved ones, the shell shocked familial unit must fake their relationship in order to seek asylum from the French government, where they are eventually moved into a housing project outside of Paris which is dominated by gang activity.

As Dheepan assumes the role of the janitor for the establishment, Yalini is hired as the caretaker for a local invalid, whose son Brahim (Vincent Rottiers) is released from prison and begins to stir up trouble as he regains the territory he left behind. While the disparate couple depends on teenager Illayaal to assist in communicating in a language they do not know, the three of them eventually adapt to a sort of rhythm in their new capacity, eventually compromised by the growing aggression all around them.

Two years after its Palme d’Or win, Dheepan perhaps exists a bit more favorably outside of the festival competition battleground. Audiard, who began as a screenwriter before graduating to director in 1994 with See How They Fall, has managed to become one of France’s most notable auteurs over the past decade, remaking James Toback’s Fingers (1978) in 2005 with The Beat That My Heart Skipped, and breaking into international acclaim with A Prophet. Increasingly fixated on contemporary social issues, Dheepan finds the auteur at his most maudlin and ambitious, delivering a refugee melodrama told exclusively from the perspective of the racial other instead of formulating saviors and servitude from the usual Euro championed cloth. Initially titled Erran during production, Audiard’s film shares the name of a ghost, the dead man whose papers allow three people to flee. If only the remaining narrative were able to retain this same level of perversely poetic displacement.

The essence of Dheepan rides on the shoulders of its three central performances, particularly Antonythasan Jesuthasan, a celebrated playwright and novelist whose own background as a child soldier with Sri Lankan militant group Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in the 1980s supersedes Audiard’s film. While his history certainly imbues the film with some extra depth, the film also feels notably removed from the specifics of Sri Lanka’s Tamil warriors, so much so the film’s tangential sequence featuring figures from Dheepan’s past seeking him out in France rings false.

While Audiard prizes the perspective of its three refugees, the screenplay, which he co-wrote alongside Thomas Bidegain (director of the celebrated Les Cowboys, 2015), and Noe Debre, features the same overwrought beats of his previous 2012 feature, Rust and Bone, which similarly featured desperate characters in dire circumstances. Audiard unfortunately projects unnecessary melodrama onto a scenario which rushes through a rather wan romantic connection with Srinivasan’s Yalini and into a bloody finale of vigilantism, stripping away the subtleties which harrowed this newly formed family in the unfavorable housing project of the supposedly more affluent French culture.

Disc Review:

US distributor IFC lucked out in purchasing Dheepan in advance of its Cannes premiere, which in turn secured it a place in Criterion’s library. Presented here as a high-definition digital master in its original aspect ratio 2.40:1 with 5.1 surround audio, picture and sound quality are astutely mixed in the transfer of this social-realist mode photographed by first time DP Eponine Momenceau. Criterion includes an audio commentary track featuring Audiard and screenwriter Noe Debre along with several extra features.

Jacques Audiard:

Criterion conducted this twenty-one minute interview in Paris with Audiard in February 2017, who describes cinema as the act of “looking,” and credits cinema as having the power to engender visibility and dignity to those whose narratives have remained undefined.

Antonythasan Jesuthasan:

Criterion interviewed Jesuthasan in Paris in February 2017 for this twenty-one minute segment, who speaks of his childhood experiences.

Deleted Scenes:

Nine minutes worth of deleted scenes are included (with optional audio commentary).

Final Thoughts:

While Dheepan has elevated the international renown of Jacques Audiard, this familiar refugee saga is perhaps his least cohesively formulated melodrama to date.

Film Review: ★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆