Glancing over the cinematic output from any particular year in the 1970s confirms the era to stand as a fossilized epoch from America’s mainstream acceptance of the auteur. Mulling over the embalmed nectar of what’s been coined the era of New American Cinema, a heyday of prolific auteurs churning out priceless output at the often confused behest of the studio system, we find a trailblazer in this movement to have been ineffable, unparalleled Robert Altman, a director who rose up by accident after twenty years of television with the idiosyncratic box office success, M*A*S*H (1970), which was technically his third feature film (following the compromised Countdown, and the chilly but deliciously strange That Cold Day in the Park).

Glancing over the cinematic output from any particular year in the 1970s confirms the era to stand as a fossilized epoch from America’s mainstream acceptance of the auteur. Mulling over the embalmed nectar of what’s been coined the era of New American Cinema, a heyday of prolific auteurs churning out priceless output at the often confused behest of the studio system, we find a trailblazer in this movement to have been ineffable, unparalleled Robert Altman, a director who rose up by accident after twenty years of television with the idiosyncratic box office success, M*A*S*H (1970), which was technically his third feature film (following the compromised Countdown, and the chilly but deliciously strange That Cold Day in the Park).

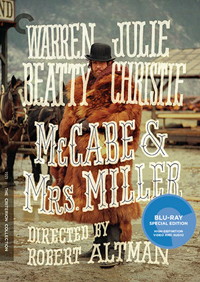

Not long after the dawn of this decade, a radical, brazen energy invigorated cinematic output. Sifting through 1971’s roster of Academy Award nominees is a dizzying recapitulation of American cinema yet to be topped, with names like Friedkin, Pakula, Nichols, Bogdonavich, Jewison, Schlesinger, Kubrick (not to mention the foreign auteurs in contention, with Petri, Bertolucci, Troell, Kurosawa, De Sica, and others) on the same platform. Nestled among these names is a Best Actress nod for Julie Christie in Altman’s daring anti-Western, McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Ultimately a box-office failure, like many of the titles from Altman’s most prolific period, it has been critically recuperated as a pillar within the genre whose rigid formulations he wished to denigrate and reinvent. Adapted from Edward Naughton’s novel McCabe, Altman claimed to tackle the most clichéd of Western narratives for his own purposes of gritty frontier realism in this tale of a man and a woman who alight in a developing mining town and open a whorehouse.

The inconsequential mining town, Presbyterian Church in the Pacific Northwest, is in the throes of development, industrial minded humans intent on wrenching it out of a wet, snowy primordial goop. Into this disorganized chaos arrives a mysterious stranger (Warren Beatty), who rides into town through the near constant drizzle. An amiable gambler, he sets up a game of cards in the local saloon while the other bar denizens whisper about him. The saloon owner (Rene Auberjonois) thinks his name is “Pudgy” McCabe and he once killed a man. But McCabe aims to open a whorehouse in this town predominantly inhabited by the men tasked with building it. Buying several ‘strumpets,’ as he calls them, he sets some ladies up in tents until a serviceable building can be erected. Meanwhile, a Cockney prostitute-turned-businesswoman arrives, Constance Miller (Julie Christie), who convinces McCabe to partner up with her as she knows how to tend to the women. Soon, the two have a lucrative business venture on their hands. But when Sears (Michael Murphy) and Hollander (Antony Holland) arrive, savvy business men who art part of a larger mining company, they make McCabe an offer to buy his business. Constance knows what it means if their offer is refused, but since McCabe is a gambling man, he just can’t seem to help but better his take.

What seems to be most appreciated in the Western genre are its familiar tropes, including a heroic figure, perhaps an illogical but dramatically necessary love interest, the threat of sinister forces, and eventually an overarching salvation no matter the ultimate consequences to narrative integrity. As critic and novelist Nathaniel Rich points out in his essay included in Criterion’s release, Altman had labored extensively in prized television artifacts of the genre, which would most likely explain his loathing for such staunch expectations.

McCabe and Mrs. Miller, like several of his other films, is an assault on the genre and audience expectations. Like Sergio Leone before him, Altman set out to show a more realistic landscape of an undeveloped American frontier. This was a place of injustice, disease, murder, misogyny, and a testament to not just the cheapness, but the frivolity and futility of human existence. Not only is McCabe and Mrs. Miller a bleak film, it’s an almost unsurpassably melancholy one. Amidst the tattered tents and bare infrastructures of Presbyterian Church, a town destined to be overruled by a vestigial capitalistic maw of industry, the snow and mud and endless muck makes this an overwhelmingly unpleasant location. And yet, Altman creates a sense of nostalgic beauty nevertheless. Much like Mark Rydell’s Canadian set D.H. Lawrence adaptation The Fox (1967), there’s an unbearable winter chill to the film, further enhanced by his then experimental visuals with DP Vilmos Zsigmond, who coats frames with a fog meant to instill an antique fragility. By the end of the decade, Altman would take this particular aesthetic to unsuccessful extremes with the sci-fi exercise Quintet (1979), this time with French DP Jean Boffety, who previously lensed Thieves Like Us (1974).

If there is such a thing as a perfect film, it could be a distinction argued for several of Altman’s films, specifically from this decade, where he plunged the medium to extradimensional depths, whether it be with his idiosyncratic rendering of dialogue (Nashville, 1975), or cinema as an abstract psychological painting (3 Women, 1977). But McCabe and Mrs. Miller is an early example of straddling both of these techniques. Assisting in the screenplay adaptation were his two leads, Beatty and Christie, the latter accomplishing a much more important role than the one outlined in Naughton’s novel, which accounts for her addition in the title. Christie is steely and scintillating as a resilient frontier woman who knows how to spin opportunity into advancement. Her complicated relationship with Beatty’s McCabe is elicited in subtle nuance—she’s attracted to him, but to bed him, she still has to smoke opium. Her change in demeanor is noted by McCabe, but he’s too self-involved to realize why. Beatty’s McCabe is surely the antithesis of the frontier hero, swallowed by his ridiculous fur coat and denying a vicious reputation (once owner of the silly nickname ‘Pudgy’) following him thanks to local saloon owner Rene Auberjonois, a man who seems a tad jealous at McCabe’s success. A host of other Altmanesque players round out a notable supporting cast, including his discovery Shelley Duvall (who starred in his previous Brewster McCloud, also a flop but one of his most effortlessly magical films), Michael Murphy, William Devane as a useless lawyer, and Keith Carradine as an unfortunate cowboy (who kinda sorta looks like the male version of Duvall at this age).

Firmly defining the landscape is Altman’s famed anachronistic use of three Leonard Cohen tracks which solidifies McCabe and Mrs. Miller as a poetic vision of a culture struggling to pull itself out of nature’s chaos—a cold-hearted and cruel hell.

Disc Review:

Heretofore, McCabe and Mrs. Miller existed on a middling transfer on an unimpressive DVD release, so Criterion’s new 4K digital restoration is the first proper release of the vintage title, one of several reasons to be excited for this indelible addition to their collection. Presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.40:1 from the original 35mm camera negative with the original monaural soundtrack remastered from the 35mm magnetic tracks, it’s an incredibly polished presentation. Plus, the disc is loaded with bonus features.

Way Out on a Limb:

Criterion produced this hour long 2016 documentary (its title a playful reference to an infamous book by Beatty’s sister, actress Shirley MacLaine) concerns the making of the film and features interviews with casting director Graeme Clifford, script supervisor Joan Tewkesbury, and actors Rene Auberjonois, Keith Carradine, and Michael Murphy.

Cari Beauchamp and Rick Jewell

Criterion produced this thirty-six minute 2016 conversation between film historians Cari Beauchamp and Rick Jewell, who discuss the title in reference to Altman’s career, the New Hollywood, and the western genre.

Behind the Scenes:

This nine minute featurette was shot on location in Canada in 1970 and documents the building of the film’s town.

Leon Ericksen:

The following is a thirty-seven minute excerpt from a 1999 interview at the Art Directors Guild Film Society in Los Angeles, which hosted a conversation between McCabe and Mrs. Miller’s production designer Leon Ericksen, led by his colleague, production designer Jack De Govia. The film’s art director, Al Locatelli, is also on hand.

Vilmos Zsigmond:

Two interviews featuring cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond (who passed away in 2016) where he discusses his work on McCabe and Mrs. Miller. The first is a 2005 interview with the American Society of Cinematographers by filmmaker and DP Michael Goi, while the second is from a 2008 documentary No Subtitles conducted by filmmaker and DP James Chressanthis.

Steve Schapiro Photo Gallery:

Photojournalist Steve Schapiro was hired to shoot “special photography” while he was a set photographer on McCabe and Mrs. Miller, and several stills have been curated from his archives for the release of this disc.

The Dick Cavett Show:

Film critic Pauline Kael appeared on The Dick Cavett show on July 6, 1971 to defend the film against early negative criticism, and a ten minute segment is included here.

Final Thoughts:

Like a beautiful but depressing dream, McCabe and Mrs. Miller can at last properly seep into the cultural subconscious with Criterion’s legitimizing restoration.

Film Review: ★★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆