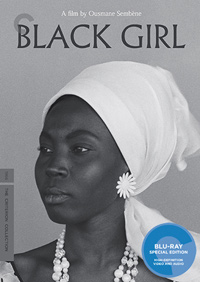

To speak of African cinema, one must begin with a discussion of Ousmane Sembene, the Senegalese auteur credited as the father of African film. Active from the 1960s until the early 2000s, he would only unveil nine theatrical features across his five decades of work, and most of these were made prior to the 1980s. Yet his contributions to cinema remain indelible, beginning with his superb 1966 debut, Black Girl, the first film to be released by a sub-Saharan director, a slim yet strikingly efficient portrait about race, class, and servitude in a world whose post-colonial attitudes are merely euphemistic. Arguably Sembene’s most internationally renowned title, the title’s format and use of its protagonist’s omniscient, often tragic and eloquent narration makes Sembene’s initial offering a clear comrade to the era’s developing Nouvelle Vague. The time and place is significant, set only six years after Senegal gained independent sovereignty from France. Ironically, the film proves progressive attitudes are almost always initially a myth as it focuses on a woman who is complicit in her own servitude/slavery, now a state referred to as something else but with the same emotional ramifications.

To speak of African cinema, one must begin with a discussion of Ousmane Sembene, the Senegalese auteur credited as the father of African film. Active from the 1960s until the early 2000s, he would only unveil nine theatrical features across his five decades of work, and most of these were made prior to the 1980s. Yet his contributions to cinema remain indelible, beginning with his superb 1966 debut, Black Girl, the first film to be released by a sub-Saharan director, a slim yet strikingly efficient portrait about race, class, and servitude in a world whose post-colonial attitudes are merely euphemistic. Arguably Sembene’s most internationally renowned title, the title’s format and use of its protagonist’s omniscient, often tragic and eloquent narration makes Sembene’s initial offering a clear comrade to the era’s developing Nouvelle Vague. The time and place is significant, set only six years after Senegal gained independent sovereignty from France. Ironically, the film proves progressive attitudes are almost always initially a myth as it focuses on a woman who is complicit in her own servitude/slavery, now a state referred to as something else but with the same emotional ramifications.

Diouana (M’bissine Therese Diop) believes she has found a way out of Dakar when she is offered employment by a wealthy white couple (Anne-Marie Jelinke, Robert Fontaine) who live in Antibes, France. However, once she arrives in her new capacity as a housemaid/servant/babysitter, Diouana realizes she is at the mercy of these white people who are wholly ambivalent towards her own desires or happiness in her new realm. Eventually, her attitude causes extreme conflict with the Madame of the house, who demands Diouana dress plainly and in a maid’s uniform at all times.

Sembene opens his film ruefully, a shot of a glaringly white ship bringing Diouana to her new quarters. Such imagery conjures a host of negative associations, not only because of the color of the receptacle bringing its hopeful young woman to a demeaning new existence, but also the historical ghosts of those slave ships which forcibly uprooted denizens of the dark continent to be used as chattel for the Americans a century prior. In this supposedly progressive new era, what is it saying about African peoples who now willingly board boats to become prisoners for wealthy white people in foreign countries?

What follows plays like the oral diary of Diouana, quickly disillusioned by her inability to exact any agency, trapped by cultural limitations in a rather dull existence in Antibes, antagonized by her white employer, a woman also obviously dissatisfied by social customs. Bored and spoiled, Anne-Marie Jelinek’s Madame (the only screen credit of the performer) reveals her own subconscious racism, a white woman who believes herself to be better than her servant, unwilling and uninterested in directly communicating with her. As the Monsieur, Robert Fontaine (who has a Klaus Kinski sort-of vibe), is equally unable to see anything from Diouana’s perspective. Sembene includes an incredibly insightful moment when he reads aloud a letter from her mother in Senegal, a document Diouana cannot read and her mother did not write. Requesting money from her silent daughter, the guilty white master immediately begins to write a letter in what he believes to be Diouana’s voice, never considering (as her narration tells us), her mother never wrote the letter and it’s as much a potential scam as their reply will be, a document unable to convey how Diouana truly feels because she herself cannot write it.

All around Diouana is a constrictive system of control. At home, she flippantly allows a handsome suitor (Momar Nar Sene) to court her, a man who chastises her for gaily skipping across a public monument. Diouana somewhat ignores these controlling masculine tendencies because she knows she has a brighter future in France, detailing how her passive ambivalence, which the Madame probably read as a ‘white’ trait (judging from her disdain for the other women desperately clamoring for work on the street), secured her this opportunity. Eventually, her repeated refrain is, “Why am I here?” Eventually this becomes the essence of lamentation, and Sembene’s visual motifs take on a jagged cruelty, such as a local mask Diouana gives her employers as a gift. Early on, we see this black mask as a dark speck looming in the great expanse of a white wall, eventually serving as a double symbol for Diouana, who is not allowed to be herself and is literally drowning in the sea of uncompromising whiteness around her. Madame’s guests snicker about her blackness and her unresponsiveness, referring to her as having the instincts of an animal.

The original French language title La Noir de… more aptly conveys Sembene’s intentions, as this translates to The Black Girl of…, signifying she is owned by someone (rather than the potentially defiant read one could project on Black Girl). As the titular figure, M’bissine Therese Diop (who’s only other credit is Sembene’s 1971 title Emitai) gives a formally characterized, complex performance with a series of stone-faced facial expressions which eventually boil over into reckless abandon and then hopelessness. Sembene’s inclusion of her narration serves to enhance these subtle changes, as well as the notable juxtapositions to her daydreamy memories in Senegal just prior to her move to France.

Diouana plays like the deliciously rebellious sister of Helga Crane, the main protagonist in Nella Larsen’s underrated novel Passing (1929), another black woman refusing to be demeaned for her race or gender, but whose pride eventually brings tragic demise. Tonally, Black Girl is also reminiscent of Octave Mirabeau’s The Diary of a Chambermaid, and of the three film adaptations of this text, Sembene’s compares to Luis Bunuel’s 1964 version starring Jeanne Moreau as Celestine, a maid with equal disdain for the frivolous cruelty of the wealthy and the privileged. Fifty years later, Sembene’s film remains the prototype on the same cinematic subjects, including for Jean-Paul Civeyrac’s 2014 title My Friend Victoria, a Doris Lessing adaptation about a young black woman whose life is marked irrevocably by her interactions with a wealthy white family. Half a century after Sembene’s trailblazing Black Girl, we exist within a world which still dominated and informed by a white, masculine climate.

Disc Review:

Fittingly, Criterion’s first Ousmane Sembene inclusion is his 1966 debut (one can only hope they save other portions of his filmography from obscurity), treated to a new 4K digital restoration, presented in 1.37:1 with an uncompressed monaural soundtrack. The film’s scintillating black and white cinematography, including beautifully photographing portions of Senegal as well as the Antibes its main character so rarely gets to see, are pristine in this transfer. Criterion outfits the release with some not to be missed bonus features, including Sembene’s first 1963 short film.

On Ousmane Sembene:

Criterion conducted this twenty minute 2016 interview with filmmaker and professor of French Samba Gasjigo (the 2015 documentary Sembene!) to discuss characteristics of Ousmane Sembene’s work.

M’Bissine Therese Diop:

Criterion conducted this twelve minute 2016 interview with M’Bissine Therese Diop who discusses her role in Sembene’s film. The actor discusses her initial interests in dressmaking rather than cinema.

On Black Girl:

Filmmaker and cultural theorist Manthia Diawara is on hand for this twenty-one minute 2016 interview courtesy of Criterion, discussing the analyzing the significance of Black Girl.

Color Sequence:

The British Film Institute restored this single color sequence from an original 35mm print originally shot for Black Girl, which was later replaced by a black and white counterpart to match the rest of the film. The minute long sequence is meant to convey Diouana’s sense of wonder as she arrives in Antibes.

Prix Jean Vigo:

Black Girl was awarded the Prix Jean Vigo and this two minute excerpt from a March 22, 1966 broadcast of the French television program JT de 20h features an appearance by Sembene.

Borom Sarret:

Ousmane Sembene won first prize at the 1963 Tours Film Festival in France for his directorial debut, the short film Borom Sarret. The twenty minute film has been restored and included in its entirety here.

Sembene – The Making of African Cinema:

Manthia Diawara and Ngugi wa Thiong;o made this hour long documentary in 1994 which focuses on the philosophies and aesthetics of Sembene’s cinema through conversation with Diawara, film students, and director John Singleton (Boyz n the Hood; Poetic Justice).

Final Thoughts:

One of the most notable titles from African cinema as well as the 1960s, Sembene’s portrait of a young Senegalese woman whose dreams are swiftly crushed by the cruelty of white privilege is as emotionally potent today as it was five decades ago.

Film Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆