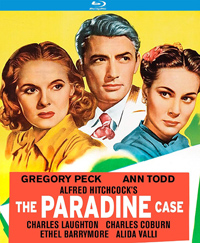

One of Alfred Hitchcock’s neglected masterpieces is his 1947 courtroom psychodrama The Paradine Case, the director’s last contractual obligation under David O. Selznick, which resulted in some untoward casting compromises. A study in shifting power struggles laid over what would appear to be a routine courtroom drama, this subtle study on displaced objects of desire features some of Hitchcock’s most impressive visual language as regards paranoia, suspicion, and control.

One of Alfred Hitchcock’s neglected masterpieces is his 1947 courtroom psychodrama The Paradine Case, the director’s last contractual obligation under David O. Selznick, which resulted in some untoward casting compromises. A study in shifting power struggles laid over what would appear to be a routine courtroom drama, this subtle study on displaced objects of desire features some of Hitchcock’s most impressive visual language as regards paranoia, suspicion, and control.

Lensed by Oscar winning DP Lee Garmes (who knew a thing or two about obsessively framed females having shot Marlene Dietrich in Josef von Sternberg’s Morocco and Shanghai Express), Gregory Peck becomes uneasily infatuated with his client Alida Valli, an impeccable beauty charged with murdering her blind husband. Confusing his duties as lawyer with his desire to be her lover, lust and love create a subtext about the blind leading the blind as Hitchcock coils us tighter than Valli’s coiffed tresses into its visual frenzy.

When Maddalena Paradine (Alida Valli) finds herself arrested for suspicion of poisoning her rich, blind husband, a decorated WWI hero, family solicitor Sir Simon Flaquer (Charles Coburn) acquires the services of the young but famous barrister Tony Keane (Peck). Upon consulting his new client, Keane finds himself falling in love with her, despite his eleven-year marriage to his wife Gay (Ann Todd). As the case progresses, Keane attempts to point suspicion at Paradine’s faithful French Canadian valet Andre Latour (Louis Jordan) much to the chagrin of his beautiful, aloof client.

The Paradine Case arrived after Hitchcock’s pair of Ingrid Bergman starrers Spellbound (1945) and Notorious (1946), reuniting him with star Gregory Peck of the former title, and before his then revolutionary Rope (1948), which had an undeniably queer subtext and was composed of ten seamless shots. Hitchcock was apparently keen to cast Bergman again (who would later appear in the unsuccessful Under Capricorn in 1949) and even Greta Garbo, but was rumored to have relinquished his principals and final cut of the film to producer David O. Selznick, with only Ann Todd hand selected by the director.

Whatever his purported lack of enthusiasm, it certainly isn’t apparent in the intoxicating close-ups of Valli, in what would be the Italian star’s introduction to a short-lived Hollywood career (following a scandal, she would return to Europe to appear in iconic films from Georges Franju and Luchino Visconti, her later career spiked with healthy doses of exploitation and genre films, such as Argento’s Suspiria). And yet, she’s a rather cold and inexpressive object of desire, keeping her overly helpful barrister at arm’s length. Notably, her dead husband was a blind man, leading Peck’s Keane to observe she was “his eyes,” and Valli would later appear as the procurer of young women for devious medical experiments in Eyes without a Face. But here, she’s the center point in this murder of a nobleman, tainted by her relationship with his slavish valet, the winsome Louis Jordan. A jealous tension between the valet and the barrister informs the dramatic tension of the second half as we deduce just how dysfunctional the Paradine household was.

Class and gender issues are the intersecting forces at play in The Paradine Case, and how control can be usurped, at certain times, from the hands of the white, patriarchal hierarchy. Seemingly as a stand-in for Hitchcock himself is Charles Laughton as a sneering judge (as his wife, a doddering Ethel Barrymore scored an Oscar nod for Best Supporting Actress), a master manipulator merely tolerated by beautiful women contending with his control, and one who finds Peck an overly emotional presence in the courtroom yet deviously makes a pass at Ann Todd during an otherwise uneventful dinner party. Todd, as boring and bland as her distressed trophy wife tends to be, is arguably the only real emotional component, having to contend with her husband’s obvious attraction to a toxic femme fatale, and one whose fate will ultimately dictate the future of her marriage. In retrospect, her name provides a coincidental alignment with Jordan’s Latour, the other powerless paramour—when a wife’s name is Gay and her husband is no longer attracted to her, there’s something unavoidably ‘queer’ afoot.

The coded confusion of Louis Jordan’s handsome valet is also of interest. Hitchcock reportedly regretted casting the handsome actor, wishing to have suggested something a bit more degrading by forcing Maddalina Paradine to not only desire someone below her station physically as well as socially, but also enhancing the slight of her physical rejection of her hotshot lawyer.

Much ado is made of how ‘queer’ Jordan’s valet is long before he appears on screen, an overprotective servant who is painted as a misogynistic dog who loathes women and wishes only to serve the will of his master. “He despises all women,” we’re told, although this invariably is not the case. However, his powerlessness and subsequent tragic behavior leaves a shadow of a doubt about his own desires—which Paradine did he actually want to serve?

Because all of these toxic subtexts are all left naggingly unconfirmed, audiences are forced to contend with the superficial courthouse antics of The Paradine Case, which isn’t quite as turbulent as all the unspoken elements underneath it. Andre Bazin raved about the film and Hitchcock’s accomplishment here with a “famous impression of anxiety…due entirely to his speed and his frames of arrivals and departures.” In particular, Bazin cites one of the film’s most stunning sequences as the camera pans around Jordan on the witness stand as Valli remains the centrifugal force.

The Paradine Case isn’t so much about any of its main characters in pursuit of justice, but, perversely, for the fulfillment of each of their own selfish physical desires. Peck’s usual irrefutable nobility is questioned from his first instance with Valli, as is Laughton’s ability to be impartial. Todd’s reluctant sacrifice for her husband’s erotic fulfillment is questionable, and Valli’s inscrutable femme fatale married a blind nobleman for his money but obviously forced another to meet her more amorous needs.

Adapted from a 1933 novel by Robert Hichens, Hitchcock’s wife Alma Reville received credit for an adaptation she took over from James Bridie and Ben Hecht (Leave Her to Heaven), although Selznick apparently retooled this as well. The film’s neurotic energies belie something much more devious than its simplified finale of punishment and forgiveness outwardly implies, as no one’s cravings are actually satisfied. Most likely, it’s no mistake Reville imbued Todd’s long suffering wife the only possible pseudo satisfaction, returned to a marriage where she’s only too aware of her husband’s limited desire for her.

Disc Review:

Kino Lorber releases this Hitchcock title as part of their Studio Classics, presented in 1.33:1. Picture and sound quality are pristine (the release offers a restoration comparison), and Garmes’ sumptuous close-ups and Valli are accentuated by a score from Franz Waxman. Kino takes pains to include several bonus features (including an audio commentary track from Hitchcock authors Stephen Rebello and Bill Krohn).

Hitchcock/Truffaut – Icon Interviews Icon:

A thirteen minute audio clip of a moderated interview between Francois Truffaut and Hitchcock pertaining to The Paradine Case.

Cecilia & Carey Peck:

Gregroy Peck’s children Cecilia and Carey share memories their father shared with them on Hitchcock in this eight minute segment.

1949 Radio Play:

The 1949 radio play version is included here, with Joseph Cotton in Peck’s role, while Alida Valli and Louis Jordan reprise theirs.

Peter Bogdanovich Interviews Hitchcock:

A near sixteen minute audio excerpt of Peter Bogdanovich interviewing Hitchcock on The Paradine Case is included here.

Final Thoughts:

More than just an excellent example of Hitchcock’s craftsmanship, The Paradine Case is an intriguing stew of subverted desire and the denial of satisfaction, and remains one of the auteur’s most subtly perverse offerings.

Film Rating: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Rating: ★★★/☆☆☆☆☆