At the time of its production, Louis Malle’s 1978 title Pretty Baby (the title derived from the Tony Jackson song) was quite the scandal, a period piece frankly depicting child prostitution in turn of the century New Orleans. But like many provocative titles from the period (another being Richard Brooks’ Looking For Mr. Goodbar), decades of suppression has resulted in unavailability and a disappearance from modern cinematic conversations. Recently made available courtesy of the Warner Bros. Archive collection (solely on DVD) this is property begging for a more masterful restoration.

At the time of its production, Louis Malle’s 1978 title Pretty Baby (the title derived from the Tony Jackson song) was quite the scandal, a period piece frankly depicting child prostitution in turn of the century New Orleans. But like many provocative titles from the period (another being Richard Brooks’ Looking For Mr. Goodbar), decades of suppression has resulted in unavailability and a disappearance from modern cinematic conversations. Recently made available courtesy of the Warner Bros. Archive collection (solely on DVD) this is property begging for a more masterful restoration.

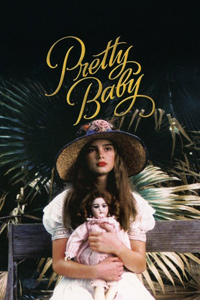

In the Red Lights district of 1917 New Orleans, legal prostitution is on the wane as a surge of conservative, religious rhetoric begins to sweep through the country. Nell (Francis Faye) owns a booming brothel in the famed Storyville district, and one of her most notable employees is Hattie (Susan Sarandon), whose twelve-year-old daughter Violet (Brooke Shields) has grown up within the house. When a curious photographer, E.J. Bellocq (Keith Carradine) arrives on Nell’s stoop in hopes to photograph her women, Hattie and Violet are the only ones awake, and thus begins a rather obsessive relationship between the soft spoken artist and his subjects. Hattie, however, has her sights set on leaving the brothel, while Violet’s beauty enables Nell to request a hefty price for the man wanting to buy her virginity. When Hattie leaves with her fiancé, Violet is left to fend for herself.

Premiering at the 1978 Cannes Film Festival, where it picked up the Technical Grand Prize, many dismissed Malle’s controversial title as child pornography, mostly thanks to a nude sequence featuring 12 year old Brooke Shields. However, Pretty Baby is neither exploitational nor pornographic, instead a rather sad coming-of-age tale from a particularly inhumane historical moment for those (particularly women and children) operating on the social periphery. In many ways, Malle captures a poetic nostalgia not unlike Peter Bogdanovich’s comedic rehash of the birth of cinema in his 1976 film Nickelodeon, though this is certainly a much less celebratory subject matter. The comparison is perhaps is enhanced by the film’s screenplay from Polly Platt, ex-wife and longtime collaborator of Bogadanovich.

A delightful mix of notable actors compose the vibrant supporting characters in the brothel, including piano player Antonio Fargas (in a sequence where bidders vie for the virginity of Shields, Malle holds tight on his face to capture a complex mix of emotions), and fellow prostitutes such as a heavily accented Diana Scarwid (the grown up version of Christina Crawford in Mommie Dearest) and horror icon Barbara Steele. Moments featuring these lounging beauties recall the dreamy malaise of the prostitutes from Woody Allen’s Shadows and Fog (1991). Famed show tune singer Francis Faye appears in her only significant cinematic performance as Nell, the pickled brothel owner. An entertainer known for having a shtick comparable to Mae West and her endless stream of double entendre, she’s the only real distraction, grazing over bits of dialogue with notable stiltedness, especially in more banal sequences were she simply seems bored, though she comes to life dramatically in juicier bits.

The film’s most interesting elements are Sarandon and Shields (who would play mother and daughter again that very same year in King of the Gypsies). Sarandon, who was in the midst of a romance with Malle, which would continue through one more collaboration with 1981’s Atlantic City, is the epitome of selfishness, and their relationship is quite memorably dysfunctional.

Shields brings unprecedented depth to a very difficult role as a young girl that’s as stunted as she is worldly. The increasingly disturbing relationship that develops between her and photographer Bellocq has a handful of rather grotesquely charming moments, such as when he gifts and photographs her with a doll. Likewise, he leaves her a note to explain his whereabouts, not realizing she can’t read. But Violet’s aggressively adamant about all the things she does know about, mainly sex. When questioned about birth control she bristles, “Don’t tell me about the things I know.”

Disc Review:

Malle collaborated once again with Bergman’s iconic DoP Sven Nykvist, after having worked together on the more experimental film, Black Moon (1975), and they create a vision of a lush, hazy summer confined almost entirely to the interiors of Nell’s house of pleasure. This Warner Archive edition basically affords the ability to see the title, presented without frills in 1.85:1.

Final Thoughts:

Pretty Baby belongs to a fine tradition of art house cinema subjected to sensationalized, knee-jerk reactions overriding its creative integrity. While the presence of a nude twelve-year-old Shields is arguably inappropriate (one can’t help but recall the specter of Eva Ionesco here, whose mother infamously photographed her nude as a young girl, which she turned into a very personal autobiographical film in 2011, with My Little Princess), to discount Malle’s ambitions to be realistic about uncomfortable subject matter would be unwarranted. Echoes of Kazan’s Baby Doll (1956), as well as another forgotten 70s film concerning the unwanted children of brothel prostitutes, the sublime Madame Rosa (1977) provide interesting counterpoints to Malle’s Pretty Baby, film is as compelling as it is humane.

Film Review: ★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★/☆☆☆☆☆