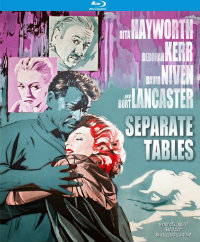

Playwright and screenwriter Terence Rattigan was an indubitable influence on mid-century British cinema. He authored several of the era’s most notable titles, including The Browning Version (1951), Lean’s The Sound Barrier (1952) Olivier’s troubled The Prince and the Showgirl (1957) and Anatole Litvak’s The Deep Blue Sea (1952), which was recently remade by Terrence Davies in 2011. But it would be a 1958 American adaptation of his play, Separate Tables, from director Delbert Mann that would prove to be his most critically lauded work, nominated for seven Academy Awards, and snagging two (Best Actor and Best Supporting Actress). By today’s standards, it’s a film that feels painstakingly melodramatic. Reconsidered within the framework of Rattigan’s own impressive oeuvre, the material hasn’t aged well, and as time has gone on, its cramped exploration of sexual dysfunction now plays like a euthanized product crippled by censorship of the author’s own sexual frustration in a homophobic world.

Playwright and screenwriter Terence Rattigan was an indubitable influence on mid-century British cinema. He authored several of the era’s most notable titles, including The Browning Version (1951), Lean’s The Sound Barrier (1952) Olivier’s troubled The Prince and the Showgirl (1957) and Anatole Litvak’s The Deep Blue Sea (1952), which was recently remade by Terrence Davies in 2011. But it would be a 1958 American adaptation of his play, Separate Tables, from director Delbert Mann that would prove to be his most critically lauded work, nominated for seven Academy Awards, and snagging two (Best Actor and Best Supporting Actress). By today’s standards, it’s a film that feels painstakingly melodramatic. Reconsidered within the framework of Rattigan’s own impressive oeuvre, the material hasn’t aged well, and as time has gone on, its cramped exploration of sexual dysfunction now plays like a euthanized product crippled by censorship of the author’s own sexual frustration in a homophobic world.

In the off season of the Beauregard Private Hotel, a group of long-term residents, with no other particular place to go, tend to feed off each other’s miseries. A shy and unassuming Major (David Niven) halfheartedly attempts to woo the frumpy Sibyl (Deborah), a cowed young woman who lives entirely under the thumb of a domineering mother (Gladys Cooper). Meanwhile, an alcoholic writer (Burt Lancaster) makes an unromantic attempt at asking the steady hotel manager (Wendy Hiller) to marry him, an offer no longer on the table when his troublemaking bombshell of an ex-wife (Rita Hayworth) drops in for a surprise visit. Several other regulars factor into these comings and goings until a scandal erupts in the local news concerning one of the hotel’s clientele.

Long term hotel guests converging into uneasy proximity has long been a cinematic situation rife with dramatic possibility. There’s a transient, almost out-of-body thrill to exploring the world outside of one’s permanent residence, and Separate Tables plays with the microcosm that often develops in these situations. The residents in this long-term private hotel are neither at home nor on an actual vacation. Instead, their day-to-day existence approaches a state of existential limbo.

As such the film most clearly resembles Grand Hotel (1932), though it’s the type of vintage theme inflected in the basis of more recent fare, such as Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). Mann’s conditioning of Rattigan’s play is most clearly influenced (and impinged) upon by the social mores of the time. David Niven’s anxious Major, who has a penchant for frotteurism, is clearly a stand in for the persecution of homosexuals, his scandalous behavior deemed degenerative (not unlike how Spencer Tracy was the white approproiation of the racial other in Fritz Lang’s Fury, 1936).

Likewise, Deborah Kerr’s unflattering casting (she did receive one of her six Oscar nods for this) as a hopelessly passive girl-woman under the control of her severely conservative mother plays like an artificial amalgamation of unsaid repressions that American cinema wasn’t able to clearly address at the time, establishing a truncated affect that confirms the film’s dated sensibilities. Other characters play like standard mouthpieces of the troubled human condition, such as Lancaster’s alcoholic writer attempting to navigate through his passion for a woman perhaps no good for him in ex-wife Hayworth, while considering the safer, reserved choice of marriage with hotel manager Wendy Hiller. “People who hate the light usually hate the truth,” he snarls at Hayworth, one of several overdone flourishes that render the film as toothless, especially considering how it all wraps up rather nicely for all concerned.

The awards glory that cemented its reputation now seems undeserving, especially considering the win for David Niven, who was up against Sidney Poitier for The Defiant Ones. Underrated character actress Wendy Hiller’s win seems less impertinent, though she would go on to appear in works more worthy of distinction (such as A Man for all Seasons, 1966). To grant this film awards recognition was a safe bet; it was playing within the censorship rules. To have awarded Poitier or Paul Newman’s turn in Tennessee William’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, also nominated that year, would have been a braver selection—but Separate Tables is an excellent example of just how unequipped the era was to rationally interpret these issues at hand. Instead, the teary breakdowns from Kerr and Hayworth, generally followed by crashing moments from David Raksin’s overwhelming score, add to the general sense of forced emotion, which is surprising considering Mann’s success with 1955’s Best Picture winner, Marty.

Disc Review

Kino Lorber’s blu-ray transfer of the classic title reflects a bit of the nonchalance with which it’s come to be regarded. There’s an absence of special features except for an option for audio commentary from director Delbert Mann and a theatrical trailer, which are just about the absolute minimum for a title once held in such high regard.

The film looks good, though set nearly entirely inside the lone setting, there’s a rather cramped, repressed visual style to the film, which feels incredibly stagey compared to other examples from the same period in DP Charles Lang’s filmography, who had recently come off of Cukor’s Wild is the Wind and would next tackle Wilder’s Some Like It Hot. An unavoidable editing snafu toward the finale, which sees a close-up on Kerr’s face for a reaction shot oddly transposed onto a sloppy background that must have been filmed out of order, creates a rather unfortunate jarring effect during a key dramatic scene.

Final Thoughts

Though a series of major accolades warrant this as an item of interest for the cineaste with a completest bent, Separate Tables is not a noteworthy title for any of the considerable talents involved. While historically it may stand as one of the most prized adaptations of the brilliant Terence Rattigan, it also happens to be his most sanitized.

Film: ★★½/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc: ★★★/☆☆☆☆☆