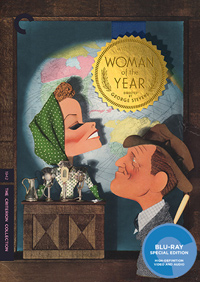

“Success is no fun unless you share it with someone,” confirms a composed Fay Bainter in George Stevens’ 1942 comedy classic Woman of the Year, a battles of the sexes comedy addressing how love and marriage doesn’t exactly function like a horse and carriage. A regal, self-assured Fay Bainter is peripheral supporting accent for the independent, whip smart international affairs correspondent played by the effervescent Katharine Hepburn in what would be her first of nine cinematic pairings with Spencer Tracy, with whom she would also share a romantic relationship until his death in 1967.

“Success is no fun unless you share it with someone,” confirms a composed Fay Bainter in George Stevens’ 1942 comedy classic Woman of the Year, a battles of the sexes comedy addressing how love and marriage doesn’t exactly function like a horse and carriage. A regal, self-assured Fay Bainter is peripheral supporting accent for the independent, whip smart international affairs correspondent played by the effervescent Katharine Hepburn in what would be her first of nine cinematic pairings with Spencer Tracy, with whom she would also share a romantic relationship until his death in 1967.

Much like the romantic sparring of the editor and reporter played by Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell in Howard Hawks’ 1940 His Girl Friday, the workplace gender dynamics brought on by the cataclysmic social shifts from WWII provide the same driving force of comedically inclined changes in perceptions regarding the roles of women. Winning an Oscar for screenwriters Ring Lardner Jr. and Michael Kanin (as well as nabbing Hepburn her fourth of twelve nominations), the smartly written comedy holds up well for its showcase of Hepburn as a feminist prototype who not only runs rings around her male counterparts but champions the notion of finding a significant other who prizes her essence.

Famed political affairs correspondent Tess Harding (Hepburn) and sports columnist Sam Craig (Spencer Tracy) both work for the New York Chronicle, but their arenas of expertise leave them at diametrically opposed odds which creates a minor intramural feud at the paper over the subject (and necessity) of baseball. Commanded by their editor to drop their public sparring, Tess agrees to attend a baseball game, and in turn, invites Sam to a private event at her apartment. Despite neither one feeling at home in the other’s realm, they fall in love, which leads to a whirlwind marriage. However, they don’t seem to know how to be alone with one another, leading Tess to throw herself into an accelerated frenzy at work and even adopting a child as a last ditch attempt to cover the communication gap with Sam. However, when the famed feminist aunt (Fay Bainter) who raised her also decides to get married, inspired by her niece’s relationship with Sam, Tess is finally confronted with the notion of what her relationship with her husband entails, and the kinds of realistic compromise expected in a marriage.

Woman of the Year was the result of Hepburn’s return from the abyss of failure, labeled box office poison throughout the end of the 1930s, which ended with the success of George Cukor’s 1940 hit The Philadelphia Story. Hepburn’s friend Garson Kanin (brother to scribe Michael Kanin) outlined the story, which Hepburn brought to producer Joseph L. Mankiewicz and also assisted in honing the film’s dialogue. Her level of behind-the-scenes control (also included the selection of her co-star, which in turn led to the decision of Stevens and not Cukor to direct) is surprising, especially considering the re-writes of the now famous finale.

Widely regarded as the film’s most memorable slapstick moment is the closing sequence in which Hepburn, determined to prove to her husband she can master the expectations of the private feminine sphere, attempts to make waffles and coffee for breakfast. Woefully inept in the process of food preparation, the exaggerated comedy works on several levels, formally allowing for the film’s sparring couple to kiss and make up, as well as for a heartfelt lesson in the kinds of compromise required in a relationship.

As regards the heteronormative mutations required of marriage as women began to enter the professional work force, the film’s most telling bit here arrives in Tracy’s speech about wanting Tess to be somewhere between the extremes of affluency and expected feminine roleplaying. “I want you to be Tess Harding Craig,” which is seen as something of a step forward, especially by 1942’s standards. This positions the dawn of a new era for a woman’s role in marriage—she doesn’t have to be property, yet she also can’t quite be herself, resulting in the hyphenated name change, a phoenix rising from the ashes to greet a brand new, compromised surname.

How Woman of the Year reflects the dueling spheres of Tracy and Hepburn in the same work setting is also of interest. Their early squabbles revolve around her dismissive attitudes towards sports. Listening to Tess being interviewed while lunching in a deli, Sam Craig is amongst a group of men riled to fervor by her suggestion of how baseball should be abolished, making her an equal enemy to the “American way of life” as the Nazi and Japanese forces the U.S. was currently fighting. Never mind her argument of how frivolousness (and obliviousness) should be abandoned in order to rally forces and focus—her feminist ideations are tantamount to treason. On a side note, it’s interesting to highlight, a year after Woman of the Year’s release, Philip K. Wrigley would found the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League in 1943 (which was in operation until 1954 and documented in Penny Marshall’s 1992 film A League of Their Own), which more overtly assisted in redefining women’s roles by assimilating the traditions of the last masculine outpost, organized sports.

Lardner and Kanin keep many of the less savory critiques of Tess at bay, although a snide comment referring to how women should be kept “illiterate and clean like canaries” more aptly suggests the resentment most men would hold for a woman of her ilk, who expertly speaks six languages and manages to combine lavish worldliness with a realm of mysterious international and political intrigue (all the more daring for the state of the world circa 1942). However, not everything about Woman of the Year plays smoothly. An awkwardly edited sequence where Craig stumbles into the bedroom while his wife holds council with another man on their wedding night feels a tad belabored, while a subplot involving Tess adopting a Greek refugee child without consulting her husband (which recalls Bachelor Mother antics mixed with Zinnemann’s The Search) is a bit silly.

Supposedly, the breakfast snafu was meant to be a comeuppance for Hepburn’s character, a woman who dared to have her cake and eat it too, surpass her male counterpart in wit, agency, celebrity, and income yet fail miserably to fulfill the duties any ‘basic’ woman could. However, despite the dismay expressed by Lardner and Kanin at the rewritten finale, there’s definite subversity to Tess Harding’s actions of ‘ineptitude.’ If a woman’s place was still popularly believed to be in the kitchen, her actions indicate this is not the cage in which she would be housed.

Disc Review:

Criterion presents this comedy classic with a beautiful new 2K digital restoration. This remastered edition is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1 and is an impressively cleaned up version of the film, the transfer taken from a 35mm fine-grain master positive made from the original 35mm camera negative. Special features regarding its director (this is the first George Stevens title to grace the collection) and stars are also included.

George Stevens Jr.:

Criterion conducted this six minute interview with the son of director George Stevens in 2017 in Washington, D.C., who shares memories of his late father and his craft.

George Stevens:

George Stevens discusses Woman of the Year in this near seventeen minute audio excerpt from 1967.

Marilyn Ann Moss:

Criterion conducted this fourteen minute interview in December, 2016 with Marilyn Ann Moss, author of Giant: George Stevens, a Life on Film, in which she discusses the director’s early career (who she describes as the Walt Whitman of American film) and the making of Woman of the Year.

Katharine Hepburn – Woman of the Century:

Author and journalist Claudia Roth Pierpont discusses the significance of Woman of the Year in Hepburn’s filmography and how it enhanced her evolution as a feminist icon in this twenty minute interview conducted by Criterion in New York in December, 2016.

George Stevens – A Filmmaker’s Journey:

George Stevens Jr. wrote and directed this near two hour documentary in 1984 about his father’s life and career, featuring interviews with Frank Capra, John Huston, Cary Grant, and Spencer Tracy.

The Spencer Tracy Legacy – A Tribute by Katharine Hepburn:

Katharine Hepburn narrates this eighty-six minute documentary made in 1986 which celebrates the career of Spencer Tracy. Interviews with Stanley Kramer, Joseph Mankiewicz, and Sidney Poitier are featured.

Final Thoughts:

Although arguably not on par with some of the later Hepburn/Tracy pairings (Adam’s Rib and Desk Set are hard to beat), Woman of the Year is still a precious lark ahead of its time, and reveals the co-stars in the early days of their formidable on-screen chemistry.

Film Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Disc Review: ★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆