As Poland’s capital, Warsaw is representative of the country’s rich and complex historical legacy, something which can’t be discussed without a thorough understanding of the severe destruction wrought upon it by the Nazis during WWII (former capital Krakow was left unscathed thanks to the presence of Franco) as well as the toll of Communism, and plenty of museums depicting significant happenings from these formative eras are aplenty. Even though the phantoms of Nazism and Communism hang heavy on the tourist experience of the city, it’s an undeniably vibrant and contemporary hub of capitalistic tendencies (surprisingly, procuring clothing is incredibly expensive, while from the street view, one sees a surplus of luxury cars).

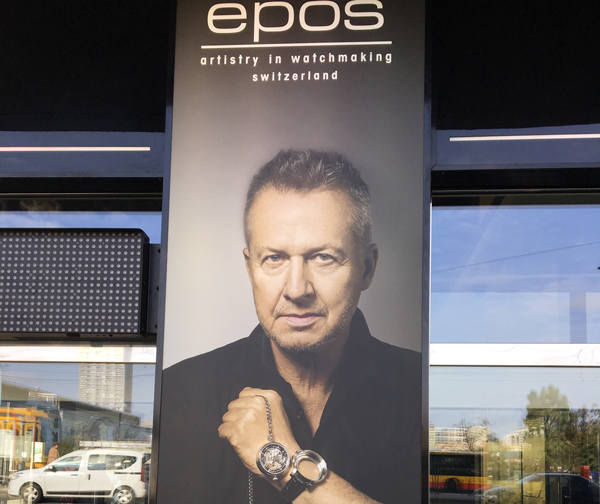

And amidst the Westernized imagery saturating the city center (you can’t go five feet without Tom Hanks’ pained expression looming out of an Inferno poster, which saw theatrical release October 14 here), including a variety of chains sporting familiar faces (Julia Roberts leers over the Italian store front of Calzedonia), there’s evidence of the country’s own significant native talent, such as Boguslaw Linda on the ads for Swiss watch manufacturer Epos. On a more disappointing front, Poland’s lack of civil rights afforded its significant LGBT population is disheartening, as well as its xenophobic administration’s (currently the socially conservative Eurosceptic Law and Justice Party) stance on immigration (none allowed).

After several sunny days, a chilly cold front ushers in the end of the 32nd Warsaw Film Festival, with an awards ceremony unveiling a handful of prizes from the Ralitza Petrova led jury (she herself won this year’s Golden Leopard out of Locarno for Godless, which also snagged an award in Warsaw from the FIPRESCI jury as the Best Debut from Eastern Europe).

Top honors went to Iranian film Malaria, the sixth feature from writer/director Parviz Shahbazi (who began his career credited on the original story for Jafar Panahi’s 1995 film The White Balloon). Premiering at the 2016 Venice Film Festival in the Horizons sidebar, Shahbazi makes a compelling and frustrating road film reflecting contemporary modes of visual expression and modeled in the steps of his predecessors. Hanna (Saghar Ghanaat) hits the road with her boyfriend Murry (Saed Soheili), hitchhiking to Tehran but ignorant of the difficulties they will run into traveling as an unrelated male and female (to check into a hotel, she requires paperwork proving her ‘morality’). They accompany a ragtag musician, Azi (Azarakhsh Farahani, brother of Golshifteh Farahani), who isn’t entirely amused to learn Hanna sent a message to her father stating she was kidnapped to explain her absence, but the aggressive patriarch is attempting to find her, assuming Azi as the perpetrator. A withering look at a lack of female agency, Malaria (so named for Azi’s band) consists of cobbled together cell phone footage from Hanna’s phone, snippets which reveal information about the characters and their predicaments. The act of recording takes on a subversive subtext in itself, as an exercise of seeing and preserving the truth.

Much of the festival’s program, particularly the Special Screenings lineup, is made up of notable auteur fare previously released on the festival circuit (the exception being the world premiere of True Crimes). Catching up with some titles neglected out of Cannes was the engaging and upsetting Clash from Egyptian filmmaker Mohamed Diab, which opened this year’s Un Certain Regard sidebar. Meant to reflect a particular period in Egypt following the military removal of the Muslim leader elected in 2012 (who took office following the grueling 2011 riots which ended the 30 year rule of President Hosni Mubarak), what transpires is meant to capture the significant struggle amongst disparate inhabitants. Taking place entirely in the back of an 8m police truck over the course of an exhausting day, Jews, Christians, and Muslims are at each other’s throats, but learn (as all humans do when forced to interact over a long period of time) they realize the humanity they have in common trumps the religious trappings which they’ve allowed to separate them. Altogether an emotionally sound venture, although at times certain diatribes sound a bit too theatrical.

On the lower end of these was the latest effort from Paolo Virzi, Like Crazy, an audience friendly melodrama about two juxtaposing female personalities who break out of a mental ward to have a Thelma & Louise/Girl, Interrupted experience. Large chunks of the film are dependent upon illogical convenience, and much of the film’s belabored emotional core remains insincere, especially regarding the construction of a very Beatrice Dalle-ish Micaela Ramazzotti character (although this won a lot of raves out of its premiere at the Directors’ Fortnight in 2016 Cannes). However, it does contain a winning turn from Valeria Bruni Tedeschi, reuniting with Virzi after their award winning collaboration on Human Capital (2013). Usually cast as the frustrated or frigid bourgeoisie staple, here she’s a breath of fresh insanity as a medication mixing motor mouth.

One of the more gripping catch-up items out of Warsaw was from Czech Republic filmmaker Jan Hrebejk, the unassumingly titled The Teacher, which details the manipulative rise of a Communist teacher in a Bratislava suburb in 1983. Like most of Hrebejk’s film, he tends to compete out of Karlovy Vary (though 2009 brought him to Berlin with Kawasaki’s Rose). His latest began a similar festival path, but netted lead actress Zuzana Maurery a deserved Best Actress win out of the fest as a monstrous Commie, a testament to the evil allowed to flourish in every regime and administration. With a little luck from a savvy US distributor, this should get Hrebejk the same sort of attention stateside as his 2006 Beauty in Trouble.

Lastly, Warsaw closed with the latest from Jerome Salle, a depiction of the life and aquatic love of Jacques Cousteau, The Odyssey. The film also capped San Sebastian this year (Salle gained initial prominence with 2005 debut Anthony Zimmer, better known as its horrendous US remake, The Tourist from 2010), and finds the director in an odd pattern of closing festivals (2013’s Zulu closed Cannes). In keeping with the stereotypes of such a slot, The Odyssey is a rather dry, uninvolving portrait of the iconic Cousteau, inventor of the ‘aqua lung’ and the progenitor of capturing unprecedented underwater footage thanks to his adventures at sea. The film revolves mostly around his familial crises with son Philippe (a rather rugged change of pace for Pierre Niney), who is a lot more like his papa than he’d care to admit. As the stalwart seafarer, Lambert Wilson gives a more or less well modulated performance as a stereotypical icon, cheating on his wife (a wasted Audrey Tautou, who totters around the boat in an alcoholic stupor, mostly in age enhanced make-up) and nonchalantly changing the way the world sees the environment. Laurent Lucas also appears in a curiously insignificant role, and despite some eye catching underwater segments, including a shark frenzy, this isn’t as involving as it should be (also, several sequences involving Cousteau and his American financers are horrendously written and performed, while Salle depends on too many lethargic montages, one set to California Dreamin,’ which make the whole venture seem uninspired).