When the Rainbow is Enuf: Jenkins Returns with Exceptional, Moving Character Portrait

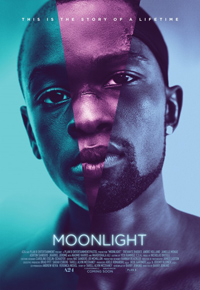

It’s been eight years since indie filmmaker Barry Jenkins debuted his exceptional directorial debut, Medicine for Melancholy (2008), a twenty-four romance between two heterosexual black twentysomethings in San Francisco, representing opposing ideologies on the construction and notion of ‘blackness’ in a large American city with a notably low percentage of black people. He’s been sorely missed, an absence something audiences were oblivious to until now as he unleashes his exceptional sophomore film, Moonlight, a character portrait of a young, gay black man told in three distinct segments. Jenkins details a nuanced odyssey of identity thwarted by cultural expectations and communal traditions with an emotional depth intelligently conveying the toxic expectations of masculine conditioning and homophobia on men and boys afflicted by the double bind of the racial other and homosexuality.

It’s been eight years since indie filmmaker Barry Jenkins debuted his exceptional directorial debut, Medicine for Melancholy (2008), a twenty-four romance between two heterosexual black twentysomethings in San Francisco, representing opposing ideologies on the construction and notion of ‘blackness’ in a large American city with a notably low percentage of black people. He’s been sorely missed, an absence something audiences were oblivious to until now as he unleashes his exceptional sophomore film, Moonlight, a character portrait of a young, gay black man told in three distinct segments. Jenkins details a nuanced odyssey of identity thwarted by cultural expectations and communal traditions with an emotional depth intelligently conveying the toxic expectations of masculine conditioning and homophobia on men and boys afflicted by the double bind of the racial other and homosexuality.

For those outside the LGBT community and its sympathizers, something like Moonlight probably sounds like a film automatically destined for the dreaded ‘niche’ audience categorization, an assumption which is merely an affront to the significant dramatic achievement Jenkins has accomplished here. Since cinema’s inception, the seventh art has been formulated for the consumption of a heteronormative status quo dominated by white representation—anything outside of such confines is expected to defer to an idea of ‘universality,’ where anything specifically defining or outlining characteristics of the ‘outsider’ automatically relegates them as threatening.

The representation of gay black men on screen remains a significantly tortured one, especially for items managing to live beyond a queer film festival circuit. Notoriously, black communities ignore or dismiss gayness (creating a continuing and problematic ‘down-low’ mentality), while the gay community continues to fetishize, exploit, and denigrate people of color by marking their skin tone as either a ‘preference’ or a detraction as a possible sexual partner (an issue unexplored by Jenkins, but important to note as another barrier in allowing black gay characters room to breathe on screen).

We need look no further than recent comments by Nate Parker and his public refusal to ever play a gay character (echoing sentiments made by Will Smith and his Six Degrees of Separation character over twenty years ago). To be gay is to emasculate and, therefore, render as non-threatening to a white majority, which embraces popular drag personas flaunted by Tyler Perry and Martin Lawrence, or kitschy flamboyant sidekicks like the ones popularly portrayed by Meshach Taylor in Mannequin (1987) or Nathan Lee Graham in Zoolander (2001). Again, this is merely a preface outlining a systematic absence of certain representations in favorable cinematic realms, and whatever detractions one may provide as evidence to critique Moonlight, the film is undoubtedly a galvanizing characterization as thought provoking as it is compelling, as heartbreaking as it is hopeful—and for many others, too close to home.

Jenkins adapts the film from a short play by Tarell Alvin McCraney, In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue, and its examination of Liberty City during the 1980s crack epidemic begins on an emotionally potent note in its first segment, “Little,” so titled for Chiron’s unfavorable nickname granted by other boys at school. Initially, the film’s focus seems to be Mahershala Ali’s Juan, a kindly neighborhood crack dealer who becomes a temporary father figure for the innocent young boy (a wide-eyed Alex R. Hibbert). A likeable turn from Janelle Monae as Juan’s emotionally generous girlfriend is also best showcased here, particularly in a sequence where Chiron inquires what the word ‘faggot’ means in a gentle but powerful dialogue.

Naomi Harris as Paula steals most of the attention away from the more subtle supporting cast members as an abusive crack addict mother, the kind of showcase which tends to attract awards glory. But by the second segment, “Chiron,” there’s no question who the story is about, and it’s here where DP James Laxton makes the most notable use of lighting (something significant to the visual language of Jenkins’ last film) with a defining moment on the beach in the moonlight, where Chiron (now Ashton Sanders) shares a rite of passage, so to speak, with his school crush Kevin (Jharrel Jerome). It’s a quiet and beautiful coming-of-age moment, textured sand on skin recalls the sweat soaked ash on the lovers in Resnais’ WWII drama Hiroshima, Mon Amour (1959).

However, easily the best chapter is the last, titled “Black,” for Chiron’s new identity (now Trevante Rhodes). Having been committed to a juvenile institution, he and his mother later move to Atlanta where he rebuilds his identity, modeling himself after early father figure Juan, becoming a muscle bound drug dealer who has fallen short of his potential. Until he receives a surprise call from Kevin (now Andre Holland), a chef back home, explaining a stranger had come into the restaurant and played a tune on the jukebox which stirred old memories. Chiron returns for a visit, an intense reunion which is played magnificently by Rhodes and Holland (particularly Rhodes, who successfully conveys the sensitive young man lurking beneath the hardened façade), incredibly meaningful glances and shifting body language relaying the information their dialogue simply cannot bridge. When Kevin gets around to playing Barbara Lewis crooning “Hello Stranger” on the juke, it allows Moonlight all the romantic splendor and energy of something as significantly sad as a Brief Encounter (1945).

Treading a well-grooved path of a denigration all too familiar to gay youths struggling to build a positive identity in a still largely homophobic world, Moonlight may not speak to all audience members equally—but whatever labels you wish to place on it, Jenkins succeeds in conveying the humanity beneath such limitations, with the kind of palpable poetic justice made possible by the potent nature of the moving image.

★★★★/☆☆☆☆☆

Reviewed on September 11th at the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival – Platform Programme. 111 Minutes.