Spill the Tea: Sissako Flounders with Tepid Brew

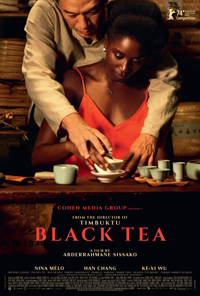

The level of ineptitude apparent in every regard of Black Tea, Abderrahmane Sissako’s first narrative feature in a decade, is downright delirious. During its development, the project was known as The Perfumed Hill, and was subject to additional drama regarding its Taiwanese funding despite ultimately taking place in Guangzhou. The end result demands to be seen to be believed, though it’s a laborious, emotional void of a film besotted by affected dialogue and shallow subtexts. Playing as if it was cobbled together haphazardly during the editing process, which is made all the more apparent by a fantastically stupid last minute reveal (the kind which invites derisive, retrospective analysis), Sissako has created a propaganda styled brochure for a travelogue.

The level of ineptitude apparent in every regard of Black Tea, Abderrahmane Sissako’s first narrative feature in a decade, is downright delirious. During its development, the project was known as The Perfumed Hill, and was subject to additional drama regarding its Taiwanese funding despite ultimately taking place in Guangzhou. The end result demands to be seen to be believed, though it’s a laborious, emotional void of a film besotted by affected dialogue and shallow subtexts. Playing as if it was cobbled together haphazardly during the editing process, which is made all the more apparent by a fantastically stupid last minute reveal (the kind which invites derisive, retrospective analysis), Sissako has created a propaganda styled brochure for a travelogue.

Aya (Nina Melo) surprises everyone by declining to marry her fiancé at the altar. Immediately fleeing the Ivory Coast, she goes to China, finding work at a tea shop owned by Cai (Chang Han). He’s unhappily married to Ying (Wu Ke-Xi), but Aya also befriends their teenage son, Li-Ben (Michael Chang). She’s also become assimilated as part of the local community, having become a friend to various shop owners, police men, and the vibrant community of other African implants at a local barbershop. They are enamored with her because of how happy she seems. She embarks on an affair with Cai, but suddenly finds herself in a similar scenario from the one she fled. Ultimately, it’s the grace of Ying which convinces her to make a potential decision.

A repeated audio signifier in Black Tea is Nina Simone, but all the saccharine conversations regarding happiness and how to tell if you’re having it suggest Pharrell Williams would have been a better fit. As Aya, Nina Melo is a striking screen presence, and the film’s opening moment, where she defies expectations and says ‘no’ at the altar, is a promising start. But then the script from Sissako and Kessen Fatoumata Tall immediately gets real wonky. Suddenly, Aya is in Guangzhou, and she spends an awful lot of time wandering around on the same streets we never roam outside of—sleepy, quaint streets which suggest the roving metropolis of Guangzhou is rather low key in foot traffic. We assume years have passed as Aya has mastered Mandarin and works in a tea shop owned by a married man she’s having a full blown affair with. His long suffering wife Ying is perfectly fine with this—-after all, he already had a child named Eva in Fontainhas, who he goes to visit at one point.

This dilemma makes Black Tea sound interesting, but these elements are stretched, strained and eclipsed by a revolving door of supporting characters, people who we learn specific details about which contribute nothing to the momentum of the narrative. The title is a reference to the kind of tea Aya supposedly reminds Cai about—but this is mentioned and never revisited. Beyond the complex tea rituals Aya must learn about, we get a whole slew of characters whose experiences are supposedly meant to reflect the diverse populace (including a large number of African immigrants, all who speak perfect Mandarin), a set-up for the ramblings of a racist Chinese grandfather who shows up late in the film.

DP Aymerick Pilarski’s glacial pans adds to the unique distress of Black Tea, likely meant to imbue the film with some sort of visual importance, but we can only watch the same characters walk slowly down the same streets so many times without questioning the purpose. What feels like a bid to ‘kick things up a notch’ involves us dropping into a dance class featuring Li-Ben.

Painfully delivered dialogue circles back to the same themes about who’s living a happy life and how they’re exactly accomplishing that. Aya’s supposed romance with Cai feels strange because she has the exact same approach to everyone she encounters (and there is a brief fantasy sequence where Ying imagines being intimate with Aya). Laughably, Li-Ben supposedly triumphs over his bigoted grandparents by informing us ‘it’s all connected’ when Aya, whose rendezvous was interrupted by Cai’s in-laws arriving a day early, plays a Mandarin cover of “Feeling Good” via Bluetooth while lurking in the bedroom.

Of course, the argument some may have for Black Tea is how these choices are pardonable because of the revelation of the final scene. But this casts an even stranger pallor over the storytelling choices which questionably engage with notions of expectation and forgiveness. Shockingly dull and overtly ludicrous, it’s a far cry from Sissako’s Cesar-sweeping third feature, Timbuktu (2024).

Reviewed on February 20th at the 2024 Berlin International Film Festival – Main Competition section. 111 mins.

★/☆☆☆☆☆