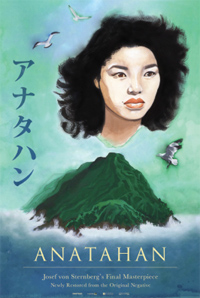

Island of Lost Souls: Von Sternberg’s Lost Post-Colonial Swan Song Resurrected

Best remembered for his indelible string of films starring Marlene Dietrich in the early 1930s, from their iconic 1930 breakthrough The Blue Angel to the string of English language films which ended in their sixth title, 1935’s The Devil is a Woman, Austrian import Josef Von Sternberg’s tortured filmography following the dissolution of his relationship with his muse are all items which have, for the most part, fallen into obscurity. After a decade of being bruised and beaten by the Hollywood studio system, being removed or replacing other directors through various high profile projects, Von Sternberg left the US to work with Japanese production studio Daiwa Production Inc. to make what would be his final theatrical feature, Anatahan (also known as The Saga of Anatahan) in 1953. Although Von Sternberg was given unprecedented control over the project, and it premiered out of competition at the Venice Film Festival, the title was not a success at the US box office (though it was well received in Japan), cementing the directorial demise of the provocative auteur. His final cinematic achievement would be this curious Lord of the Flies style examination of isolated soldiers reduced to basic intimations of humanity on a desolate island.

Best remembered for his indelible string of films starring Marlene Dietrich in the early 1930s, from their iconic 1930 breakthrough The Blue Angel to the string of English language films which ended in their sixth title, 1935’s The Devil is a Woman, Austrian import Josef Von Sternberg’s tortured filmography following the dissolution of his relationship with his muse are all items which have, for the most part, fallen into obscurity. After a decade of being bruised and beaten by the Hollywood studio system, being removed or replacing other directors through various high profile projects, Von Sternberg left the US to work with Japanese production studio Daiwa Production Inc. to make what would be his final theatrical feature, Anatahan (also known as The Saga of Anatahan) in 1953. Although Von Sternberg was given unprecedented control over the project, and it premiered out of competition at the Venice Film Festival, the title was not a success at the US box office (though it was well received in Japan), cementing the directorial demise of the provocative auteur. His final cinematic achievement would be this curious Lord of the Flies style examination of isolated soldiers reduced to basic intimations of humanity on a desolate island.

In June of 1944, twelve Japanese seamen become stranded on a forgotten island called Anatahan. The desolate environment has only heretofore been inhabited by an overseer of a long abandoned plantation, and a lone woman, incredibly beautiful Keiko (Akemi Negishi). Over the next seven years, the men’s semblance of civilization is swiftly eroded as they fight for power and control, represented mainly by the ownership of Keiko (who has a succession of several husbands over one swiftly violent forty-eight hour period). In the ensuing wreckage of an American airplane which crash lands on the island, two pistols will determine who can hold control. When Keiko suddenly disappears, the men consider themselves lost until they are eventually notified the war has ended and they will be returned to the mainland.

More respectful than might be expected considering the perspective and the material, it’s Von Sternberg’s omniscient and omnipresent narration which makes Anatahan a peculiar docu-hybrid portrait of devolving humanity (think a Richard Attenborough removed style dissection of a people and their rituals) as well as a problematic post-colonial artifact feeding into the type of whitewashing it would seem to be attempting to sidestep. Purposefully shirking subtitles, it is Von Sternberg’s voice painstakingly narrating the action—but one can never completely trust the narrator, and these people and characters, technically unable to speak for themselves, are completely robbed of agency, the playful subjects of a director finally given complete, unmitigated control over all aspects of the creative process (he did serve as producer, narrator, cinematographer, director, and adapting screenwriter from a novel by Younghill Kang and Machir Maruyama).

While this move is the underlying factor of how mankind ultimately dehumanizes itself when groups are cut off and left to their own totalitarian-like devices, who is ‘telling’ their story provides unavoidable meaning. Like Lars Von Trier would repeat several decades later, Von Sternberg’s adoption of the moniker “Von” maintains and complements aristocratic pretense eclipsing and overshadowing his authorial integrity on Anatahan, despite its cinematic significance.

Although the title Jet Pilot, a Howard Hughes production which starred John Wayne, was the last Von Sternberg premiere, (released in 1957, the troubled project was filmed in 1950), this also serves as a reminder of the significant battles the director faced as far as creative control in Hollywood. The lone intertitle of Anatahan, announcing it as a ‘postscript of the Pacific conflict” becomes even more ironic in retrospect, since this is exactly what the title has become within Von Sternberg’s own filmography.

The production followed what was Von Sternberg’s last troubled studio production, 1952’s Macau, a vehicle meant to follow in the exotic tradition of Casablanca (1942) and starring Jane Russell, Gloria Graham, and Robert Mitchum (Von Sternberg was fired by Hughes and Nicholas Ray completed the picture). The specter of white, colonialist cinematic tendencies, which can be read into the intriguing history in the locale and narrative of Macau (or his earlier and underrated The Shanghai Gesture, 1947), logically shaped the creation for something like Anatahan, a well-intentioned allegory. The film is most memorable as the introduction to Akemi Negishi as the striking “Queen Bee” Keiko, who would later star in Kurosawa’s 1965 Red Beard, the only member of this desolate outpost to use aggression and submission as means of survival, and the only character granted a sense of agency and self-preservation.

The beautifully photographed film (DP credit is shared with Kozo Okazaki, of Sydney Pollack’s The Yakuza, 1974) is finally available thanks to this new restoration courtesy of Kino Lorber. A curiously structured and presented cinematic endeavor, it reflects Von Sternberg’s particular strengths from his early days as a silent filmmaker, with subjects manipulated and glorified by the auteur as ultimate overlord. Despite its neglect, Von Sternberg considered Anatahan his greatest work, finally and fittingly restored years after the auteur’s relevance has been relegated to one particular era of film.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆