Dark but Full of Diamonds: Farhadi Incorporates Miller’s Tragic Theater for Gendered Revenge

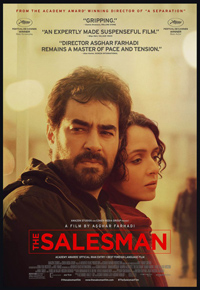

In keeping with his string of tersely titled but searing domestic melodramas, Iranian auteur Asghar Farhadi charts an uneasy discourse with Arthur Miller’s iconic 1949 play Death of a Salesman for his latest, simply titled The Salesman. Notably, this is a return to Iran for Farhadi after his 2013 French language debut The Past, though this searing indictment on the bothersome realities of vengeance and unjustifiably gendered power ethics doesn’t reach the formidable and deliciously exacting dramatics of his 2012 Oscar and nominated Golden Berlin Bear winning A Separation. Still, Farhadi’s particular theatrics remain idiosyncratic to his interests in exploring culturally specific dynamics between men and women, and have successfully elevated the international awareness and platform of Iranian cinema, and his latest (which snagged a Best Screenplay and Best Actor win at Cannes 2016) is another strident chapter on human emotions shackled by social convention.

In keeping with his string of tersely titled but searing domestic melodramas, Iranian auteur Asghar Farhadi charts an uneasy discourse with Arthur Miller’s iconic 1949 play Death of a Salesman for his latest, simply titled The Salesman. Notably, this is a return to Iran for Farhadi after his 2013 French language debut The Past, though this searing indictment on the bothersome realities of vengeance and unjustifiably gendered power ethics doesn’t reach the formidable and deliciously exacting dramatics of his 2012 Oscar and nominated Golden Berlin Bear winning A Separation. Still, Farhadi’s particular theatrics remain idiosyncratic to his interests in exploring culturally specific dynamics between men and women, and have successfully elevated the international awareness and platform of Iranian cinema, and his latest (which snagged a Best Screenplay and Best Actor win at Cannes 2016) is another strident chapter on human emotions shackled by social convention.

In the midst of rehearsing their soon to open stage production of the famous Arthur Miller play, in which they will be starring as Willy and Linda Loman, married couple Emad (Shahab Hosseini) and Rana Etesami (Taraneh Alidoosti) find themselves displaced from their newly purchased apartment when the entire complex begins to collapse. Thankfully, Babak (Babak Karimi), their co-star in the stage production, knows of a vacant apartment where the couple can immediately relocate temporarily as they await a reimbursement for their damaged apartment. Their lives suddenly in disarray, Rana mistakenly buzzes an interloper into the apartment one evening thinking it is Emad returning home, only to be physically and sexually assaulted by a man who had come to visit the previous displaced tenant, a prostitute who was greatly disliked by her socially pure neighbors. The culprit flees the scene following the indiscretion and leaves his truck behind. While Emad and Rana attempt to pick up the pieces, their emotional disconnect causes Emad to go to great lengths to solicit an eye for an eye without the interference of the law.

The opening sequences of The Salesman provide the film with its overarching metaphor of an irreparable foundational disturbance, the unsecure building and subsequent evacuation resulting in a dramatic ripple effect. Just as the central couple in A Separation is (at least partially defined) by their parental roles, Rana and Emad’s predicament here is also born out of their childlessness. Devotees of the theater, (Miller’s tweaked text, including side jokes about the downplayed sexuality of the prostitute character Miss Francis is merely a backdrop and superficial subtext), it is inferred the Etesamis and their untraditional lives and interests are the potential cause for their current state of tragic duress. The power of suggestion is the significant thread connecting (and strangling) the major movements of The Salesman, which uses Miller not so much as a treatment of American vs. Iranian values, but as an experimental, doubling arena for the theatrical business of life.

The actress playing Miss Francis in the play assumes she is being demeaned by a male co-star because portraying a woman of easy virtue invites automatic disrespect; Babak becomes infuriated at Emad adlibbing incendiary lines during a performance; a woman in a taxi is convinced Emad aims to molest her because he sits with his legs open; and, ultimately, it is Rana’s fault she was raped because she didn’t bother to check who she opened the front door of her apartment to. Had Rana and Emad had children or more conventional professions, their own lackadaisically defined routines would have been in automatic check, or so the social circles around them in The Salesman seem to imply.

We sympathize more with Shahab Hosseini’s Emad, whose chronic frustration boils over into a Death and the Maiden style attempt at truth as vengeance. Because Farhadi, once again, only implies the trauma exacted upon Rana in her shower, it allows for us to be more estranged from her untoward behavior and subsequent victimhood and more celebratory of Emad’s impassioned attempt to rectify the situation by saving his pride (and, perhaps to a lesser degree, his wife’s reputation). Farhadi reunites with his About Elly (2008) cinematographer Hossein Jafarian to construct a careful examination of bodies in spaces, the suggested control and inherent power plays in blocking.

The final, intense third act returns us to the unsafe space of the crumbling façade, a touching metaphor for the grisly and unappealing outcome of Emad’s desperate ploy for closure and revenge. But as in previous works, Farhadi’s strength lies in his ability to cast adept performers able to convey the subtle complexities of his prose, and what Taraneh Alidoosti and Shahab Hosseini (both who have previously appeared in Farhadi’s films) achieve here is exciting as it is troubling for Farhadi forces us to ask why do we sympathize with Emad and not Rana? The audience, like the community and culture around Rana, become complicit in their inability to empathize with either females or victimhood. Until the magnificent finale, that is, when Emad and company (including a particularly arresting late staged supporting turn from Farid Sajjadhosseini) are taken to task, and satisfaction for anyone quickly dissipates into the realm of the impossible.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆